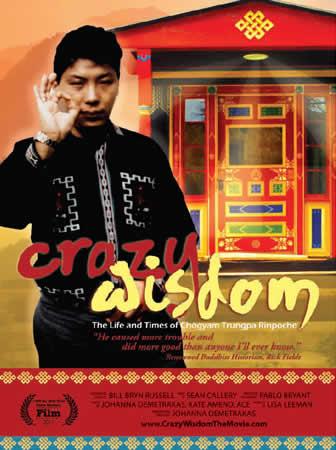

Ms. Demetrakas’ film Crazy Wisdom was instrumental in helping me understand just how strong the Buddhist voice was in the counterculture of the sixties and seventies, and why it needs to be respected as a powerful force that prompted the New Age movement. This shift had many contributors shaping it, and Crazy Wisdom celebrates the role of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche (February 1939 – April 4, 1987) in facilitating that shaping. Although Chögyam Trungpa’s name is almost a household name in Western Buddhism, until now there hasn’t been a visual collection of stories and reflections about his life. This film is a documentary, and similar to other Buddhist documentaries I’ve seen, has no narrator. With little more than some introductory and concluding text, Crazy Wisdom launches into the story of Trungpa’s flight from Tibet and settlement in Oxford and Scotland, before relocating to the United States. And it is a remarkable journey that the documentary tells.

Chögyam Trungpa was most famous for his founding of Naropa Institute and his pioneering of the idea “spiritual materialism” (a mistaken frame of mind that leads practitioners to pursue spirituality in bad faith, as a quest for ego-building). He was also famous for less conventional things a holy man would be famous for, and his biography reads like a sordid drama in Tibetan or Chinese literature about men of the cloth gone wild. But it’s much more than that, and in any case the Tibetans already have the phrase “crazy wisdom.” Our expectations of good masters are predicated on our cultural sensibilities and presuppositions of what a good master actually should be rather than what they are. Trungpa was one of those rare figures who taught his students how superficial and tautologous that was. For him, the truly good masters went (or at least tried to go) beyond culture and presuppositions.

Going “beyond” culture was the major challenge for Buddhists at this crucial juncture in history: this was a world where the great empires of the past were crumbling – and new ones were on the ascent. Most importantly in Trungpa’s context, the

Chinese People’s Liberation Army had established a socialist Republic and occupied Tibet. But the Cold War and Vietnam War highlighted an age when spirituality changed with geopolitics. The wisdom of craziness, or spirit of insanity as “inquisitiveness,” was what could enter the Western psyche unobtrusively, peacefully, and non-threateningly.

Crazy Wisdom understandably makes modest use of effects. It possesses a sombre ambience, punctuated on occasion by the humorous reminiscence by an interviewee. A startling diverse range of people were invited to speak about their experience with Trungpa, from collaborators of Naropa Institute such as teachers and writers to more personal individuals like the Master of the Household (for Trungpa’s house in the States) or his cook, and other famous representatives of Western Tibetan Buddhism such as Robert Thurman and Pema Chodron. Of course, there is also his British wife, Diana Mukpo. A young British student at Cambridge, Diana is naturally given many chances to share her thoughts about the holy man she wed, and these complex reflections she’s offering: from confessions about love at first sight to her eager, enthusiastic agreement to his proposal of marriage at some point, mixed in as well with an admission that she never really knew the innermost depths of his heart… and the fact that she saw his sleeping with other women as a betrayal. Nevertheless, she remained a loving and loyal partner.

http://www.youtube.com/embed/JzZRiE7C_Ac?feature=player_embedded

“Craziness is fearlessness,” declared Trungpa, but nor was craziness supposed to manifest itself as alcoholism. Many of his somewhat less palatable actions have generated controversy among Tibetan Buddhists for decades. Was he simply living out the path of crazy wisdom as promised, or had he regressed somewhere along the way? There are differing opinions. Even Thurman, staunch defender of Tibetan interests and a scholar of Tibetan Buddhism, had to “acknowledge flaws” in Trungpa’s addictions. But Pema Chodron is more ambivalent to the weaknesses of Trungpa, saying that she can’t come up with ground to either condone or condemn it. And I found myself largely in the same spot, especially when I started to learn about his sexuality. Trungpa’s dalliances with his female students wouldn’t be tolerated in more conservative Buddhist communities in China or Hong Kong, but at the very least he was open about his flaws with alcohol, fidelity, smoking, et cetera.

And for all his quirky pedagogical methods he had clear objectives, whether he was trying to teach his household helpers the Queen’s English (he saw American English as a symptom of an inner flaw) or setting up the “Dorje Kasung” – a group Buddhists dressed in military uniform and practicing in all the trappings of army life, like saluting and marching to drums. In these two quirks we can see his true objectives: to transform or transmute language as well as consciousness. For Trungpa, nothing could change unless one changed the way one wasbeing, and how one used discourse. Without these two incredible transformations, society would remain locked in a destructive discourse of binaries and self-deceptions and trapped in a false consciousness vulnerable not only to obvious spiritual weaknesses, but spiritual materialism too.

In any case, his achievements are undeniable. He gave the West a new kind of Buddhism appropriate to its culture. His positive affective power over his students is also palpable. Throughout my watching the film, it wasn’t unusual to see interviewees breaking into tearful emotion upon remembering their past with him. And no surprise, for his legacy is incredible.

Tibetan Buddhism is now firmly entrenched in the West and protected by its laws. Chögyam Trungpa’s authored books can be found in American and British households aplenty, and are still in circulation by Shambhala, one of the largest publishing presses for philosophy and spirituality. Even after taking all his oddities into account, especially his notion of transmuting army customs, uniforms and trappings into customs, uniforms and trappings of peace, it cannot be denied that he made a genuine attempt to skilfully transmit Tibetan Buddhism in a way that was not only understandable but effective. There is a sad irony in the fact that Trungpa’s dream of an army associated with inner peace – a transformation of discourse and consciousness – is further away than ever, especially in today’s United States. But perhaps we need not lament the fact that samsara is simply being samsara. We can rejoice at the small things that alert us to how much work remains to be done, and Crazy Wisdom achieves this in its own understated and affective way. That is a fantastic achievement in itself.

Jonathan Barbieri, the Executive Director of Shambhala Mountain Centre, said in Crazy Wisdom, “It took us ten years to figure out that he was teaching traditional Buddhism… You’re constantly feeling you’re truly journeying what is traditionally described as… ‘the path is going underneath you and you are just continually opening up to whatever you are encountering.’” And that pedagogical insight, perhaps, was the most enlightened facet to the complex character of Chögyam Trungpa.