This feature was originally published on Buddhistdoor en Español. The following is a translation of that article.

Some 90 kilometres south of Buenos Aires, outside the small rural town of Brandsen, lies the Dhamma Sukhada meditation centre. Located amid the vast grasslands of the Argentine Pampas, the main building can be seen from kilometres away. It is the land of gauchos, populated by cows, horses, and sheep that glance with suspicion at the few visitors who pass through. At the centre, one can occasionally spot foxes, hares, southern mountain cavies, and giant tegus, cautious yet relaxed, as they know they will not be disturbed.

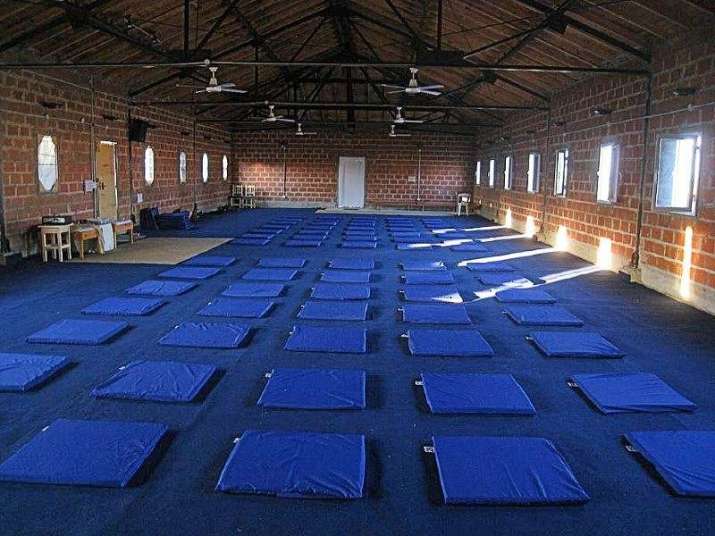

Upon reaching the centre, an old carriage wheel hanging from a post welcomes you, precisely representing the Wheel of Dhamma, a doctrine and symbol that started to circulate through India, followed by the rest of Asia, and is now rolling through these latitudes that until very recently knew nothing of the Buddha’s teachings. Much has been done there, but much remains to be done: there are trees to plant, walls to plaster, rooms to build, and a kitchen to expand. I have often heard widely traveled foreign visitors comment that it is the most austere organization founded by Burmese Master S. N. Goenka* that they have ever seen. I have also occasionally heard them mention that it is the center of which they are most fond.

At first, the vast and empty surroundings and humble facilities may cause misgivings or mistrust. It seems as if there is little to look at in this isolated and timeless place, where modernity and its interminable noise are called upon to be silenced. Upon arriving, one leaves their mobile phone, car keys, billfold, and anything else prohibited during the 10-day workshop: books, journals, music . . . practically everything except clothes and basic daily hygiene items. You cannot talk or communicate with gestures or even make eye contact. One is alone, albeit with others. The vegetarian food is abundant, but limited to breakfast at 6.30 a.m. and lunch at 11.00 a.m.—almost intermittent fasting with just a five-hour window for eating and nothing during the other 19 hours.

The practice is also rigorous. Over the course of 10 days, it starts with waking at 4 a.m. and ends with bedtime at 9.30 p.m. The task during the first three days consists simply of observing your breath, following your inhalations and exhalations as they spontaneously occur, without trying to change them. Over the course of long hours in the meditation room, the mind fights a tough battle with itself to pay attention to the simple and natural act of breathing. Thoughts move inexorably to the past or visualise an uncertain future. They dream of longed-for pleasures or old resentments and fears, deeply resisting just being present.

On the fourth day, the instructions change and the meditators are asked to pay attention to sensations that spontaneously arise. Patiently, you move through the different parts of your body, observing these sensations with the same attention and attitude employed before when observing the breath, with equanimity and without trying to influence anything.

This practice involves a whole new challenge, as the sensations are usually unpleasant at first: heat, tension, pain, pressure, itching, tightness. . . . With experience, you start to learn how the mind influences the body and how the body influences the mind, in a relationship of mutual determination. You notice that the compulsive thoughts and negative emotions settled in the deepest layers of the mind are responsible for the unpleasant sensations and, in parallel, that sensations such as those caused by the discomfort of sitting quietly for long periods of time produce thoughts of rage and aversion.

However, as the days go by and you become more accustomed to the practice, meditation becomes deeper. You gradually begin to accept simply being present with these disagreeable sensations, which start to melt away, like butter in a hot frying pan. From learning impartial attention, you gradually learn the big lesson through experience: when you cease resisting, a sacred alchemy transforms both your inner and outer realities. The body and mind become lighter and the unpleasant feelings give way to more subtle sensations. If you continue to practice with the same impartiality toward these pleasant feelings, they too will dissolve and you realise that the entire body and mind are nothing more than vibrations that come and go.

At the same time, as the days flow by and your mind becomes calmer and more observant, you gradually start to discover the beauty of the place. Where before you saw only grass, you now see a rich variety of native plants and multicoloured wildflowers. The apparently uninhabited plains are revealed as teeming with life, with a large variety of insects and birds. The smell of the earth changes from morning to evening; the moon displays its different phases; the clouds float through a limpid blue sky or cover it, promising rainfall. Thus, consciousness opens to colors, sounds, smells, flavors, and textures. You may even realise that—beyond words—there is non-verbal communication that connects everyone meditating there.

Through the Buddha’s teachings (Dhamma), which are based on the practice of sila (morality), samadhi (developing awareness through attention to the breath) and pañña (cultivating wisdom through the impartial observation of sensations), you progressively purify the structure of the body and mind and begin to be released from suffering (dukka). Thus, the apparent austerity of the surroundings and supposed severity of the practice transmute over the course of the 10 days into richness, peace, and plenitude, both internal and external. Hence the name of the centre is Dhamma Sukhada, meaning “giving the happiness of the Dhamma.”

When the course ends, the most arduous task is just beginning: applying what has been learned to daily life, which is where the true challenge rests. Through meditating, we have a tool that helps us to not react with attachment or aversion to the situations we face in daily life, maintaining the equanimity and balance of the mind. To close, I would like to transcribe the words of S. N. Goenka:

Observing reality as it is by observing the truth inside—this is knowing oneself directly and experientially. As one practices, one keeps freeing oneself from the misery of mental impurities. From the gross, external, apparent truth, one penetrates to the ultimate truth of mind and matter. Then one transcends that, and experiences a truth which is beyond mind and matter, beyond time and space, beyond the conditioned field of relativity: the truth of total liberation from all defilements, all impurities and all suffering. Whatever name one gives to this ultimate truth is irrelevant; it is the final goal of everyone. May you all experience this ultimate truth! May all people be free from misery! May they enjoy real peace, real harmony, real happiness! May all beings be happy!**

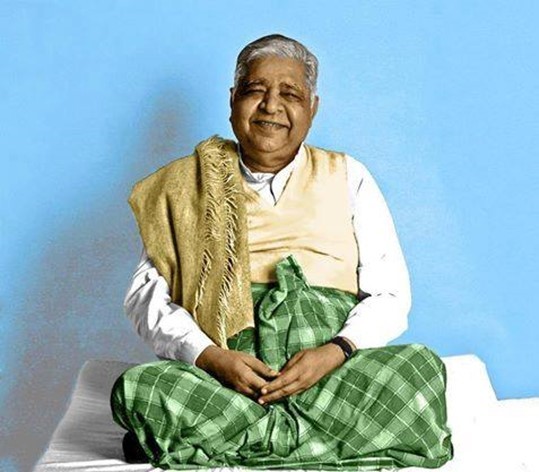

* The international organization Vipassana Meditation, belonging to the Theravadatradition, was founded by the Burmese-Indian master Satya Narayan Goenka in the 1970s. Today, this organization, which is funded exclusively through voluntary donations from students who have completed at least one 10-day meditation course, has more than 200 centres throughout the world. Vipassana Meditation has had a presence in Argentina since 1994, when the first course was held in the town of Lobos. In 2005, the Argentine Vipassana Association acquired 22 hectares of land in the town of Brandsen and construction started on Dhamma Sukhada, a centre with the capacity to accommodate 120 students after completion. Courses have been held there since 2013 and, to date, more than 100 have taken place in the country, attended by thousands of people.

** The Art of Living: Vipassana Meditation (Vipassana Meditation)

Dr. Catón Eduardo Carini has a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from the National University of La Plata (UNLP), a master’s degree in social anthropology from the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO) and a PhD in anthropology from UNLP. He works as an assistant researcher at the National Council of Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET) of Argentina and as a lecturer in cultural and social anthropology at UNLP. He became interested in Buddhism in 1999 when he began to practice Zen meditation with French master Stéphane Thibaut at the Zen Association of Latin America. He later dedicated himself to practicing vipassana meditation at centers linked to the Burmese master S. N. Goenka, as well as the practice of the Dzogchen tradition in Vajrayana, under the guidance of Tibetan master Chogyal Namkhai Norbu.