On 18 August, a team of researchers in Seoul thrilled the archeological community when its members unearthed a ceramic pot at the site of Dobong Seowon, a Confucian academy built in the Joseon period (1392–1897). To the researchers’ elation, the pot contained 77 magnificent, expertly preserved Buddhist artifacts. Among this trove of ritual objects were an intricate vajra (a double-ended implement symbolizing indestructibility), metal bells and censers, and even a metal utensil indicating ownership by the Goryeo-era (918–1392) Buddhist temple over which Dobong Seowon was built. A Cultural Heritage Administration official told the press that this was the first time such a quantity of Goryeo Buddhist relics had been found at a Confucian site. The pot had been wrapped in a straw mat before being buried, hinting that the artifacts were interred on purpose to protect them from destruction by anti-Buddhist insurgents.

The hoard’s contents, which are currently protected by the National Palace Museum of Korea and likely to be designated state treasures, are not some distant irrelevance to Seoul’s gleaming skyscrapers and high-octane stress. Despite Catholicism and Evangelical Protestantism making deep inroads into South Korea (with several high-profile cases of conflict between Christians and Buddhists), Buddhism is partly insulated from obsoleteness by the historical continuity and identity with which it provides contemporary South Koreans.

Take the ongoing dispute over two images created in Korea but, until recently, enshrined in Japan: a bronze standing statue of Tathagata Buddha from the shrine of Kaijin-jinja and a seated Kannon bodhisattva from the temple Kannon-ji, both on Tsushima Island. The designated cultural properties were taken out of Japan by a theft ring of South Koreans in October 2012. Their return was prevented by a South Korean court due to conflicting theories on how they ended up in Japan. The Koreans believe that Japanese pirates first stole them centuries ago, and the debate has ignited patriotic passions and post-World War II grudges in a way only objects of a “national” religion can.

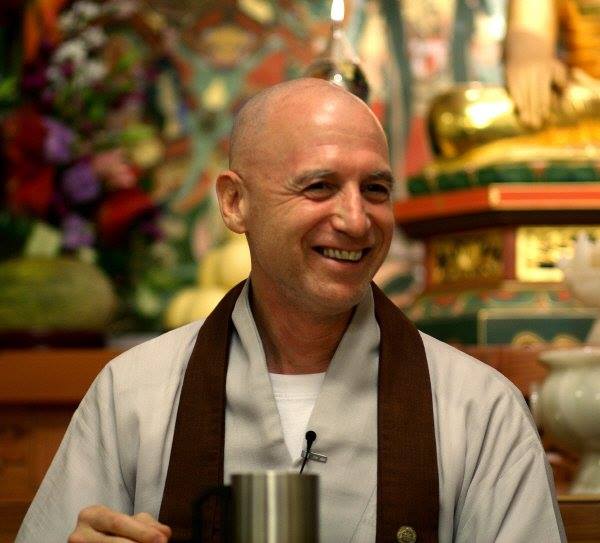

It is not just culture, art, or heritage that keep Buddhism important in South Korea. In the Subong Buddhist center in Causeway Bay, one of Hong Kong’s busiest shopping districts, one senses a hunger for more than the manufactured K-Pop and artificial glamor of Jun Ji-hyun or Kim Soo-hyun. Here I met Venerable Dae Bong, head of Musang Temple on Mount Gyeryong and a monk of Master Seung Sahn’s (1927–2004) Kwan Um School of Seon (Korean Zen). He cuts a quiet and courteous figure but remains a humorous and sharp observer of religious and social issues. Like many other contemporary teachers regardless of school or tradition, he is determined to ensure Buddhism stays pertinent not only in the West but also in South Korea, which has been his adopted home since 1984.

Ven. Dae Bong is emphatic about his relatively fortunate background—appreciation is an important aspect of Seon practice. After practicing psychology for five years and ending up in a shipyard as a welder (he stresses that he enjoyed his time building ships much more than college), in 1977 he met Master Seung Sahn at the New Haven Zen Center in Connecticut. Ven. Dae Bong had a flash of inspiration when a student asked Master Seung Sahn what was sanity and what was insanity. Master Seung Sahn had only just started learning English and so asked for a translation, which was given as “What’s crazy and what’s not crazy?” Master Seung Sahn replied that to be very attached to something was to be very crazy, to be a little attached to something was a little crazy, and to be completely unattached was to be not crazy. He continued: “So, in this world, everybody’s crazy, because everyone is attached to ‘I.’” His lucid explanation of the “don’t know mind” spurred Ven. Dae Bong to take Refuge and eventually to ordain under him.

To be free from ideas and ideology does not mean to be uncaring. South Koreans still seek spiritual answers underneath the perceived glamor and bustle. “South Korea is a much more comfortable country than it was before, but now there are major problems. What I found now in coming back after teaching in America is that our society has developed economically but the young people aren’t happy,” he says. It was striking that he seemed to understand the economic and social concerns of young people, which are different to those of older generations. “The prospects of life are a bit more daunting for our young. Everyone knows the planet is overpopulated, and the environment is in a very dangerous state.”

While Seon cannot offer more social security or better jobs for struggling young people in South Korea (or, for that matter, Hong Kong), it can certainly offer tools to weather society’s storms. From the Subong perspective, these tools are primarily meditation, chanting, and koans: “We mostly run retreats where we teach not only sitting meditation but also how to use chanting as meditation, how to use bowing as meditation, how to use washing dishes as meditation,” he reveals. According to Ven. Dae Bong, Seon’s objective is to discover the true I rather than the conventional I that is constructed by thinking.

Ven. Dae Bong is very clear about why he chose Seon over his “native” religion of Christianity: like most Western-born Buddhists, he was attracted to Buddhism’s emphasis on the inward journey to discover the mind. “Buddhism is a ‘subject’ religion rather than an ‘object’ religion like Christianity. That’s where you direct your salvation to an external deity. In Seon, it’s all about finding your true nature—and your true nature is the universe. When you’ve realized your true nature, you’re in the best position to help others.”

The Kwan Um School falls under South Korea’s dominant Jogye Order, but has actually been more famous in the West thanks to Master Seung Sahn’s extensive work in the United States and that of his American disciples. For Ven. Dae Bong, part of its success can be attributed to Master Seung Sahn’s way of teaching: “Master Seung Sahn used to say if you can find human beings’ original job, any kind of everyday job is okay. The problem is that we’re too attached to our everyday jobs to attend to our real, original job of realizing our true nature.”

Ven. Dae Bong acknowledges that Korean Buddhism has encountered (and still faces) plenty of challenges, be it from medieval Confucians or modern Christianity. High up in the lush greenery of Mount Gyeryong, Musang Temple must now bring Master Seung Sahn’s Buddhism “back” to South Korea: having been nurtured overseas for so long, it must now serve the needs of Koreans, which are at once unique and similar to those of American Buddhists. But I am confident that Korean Buddhism is like the treasure trove hidden inside the pot unearthed at Dobong Seowon. It has always been there, concealed as the world moved on in a flurry with other concerns, perhaps overlooked and underrated.

Yet, when the conditions were right for it to be rediscovered, everyone was delighted.