At 7 p.m., Lotos the 11-year-old mini-monk dashes up the stairs, his red robes billowing out behind him. He makes his way onto the monastery roof and towards the big brass gong that stands at its edge. Below him stretches the Indus Valley. Silver poplars flank the awesome river; they sparkle in the wind, catching the last rays of the sun before it sets over the mighty Himalayas. Miniature versions of the neighboring monasteries of Thicksey and Stakna can be seen in the distance.

It’s dinner time. From the various nooks and crannies of Matho Monastery, monks start to appear. The older ones, gnarled hands clinging to walking sticks, cross the courtyard towards the dining hall slowly. The young monks run past them, laughing, eager to fuel their growing bodies with the monastic elixir of rice and dahl. Among the red robes, the faces of several curious-looking dinner guests peep out: a skinny Spanish photographer, a Nepalese public relations manager and mountaineer, and a few French students of Art History and Museology in Paris.

“Julley”s (a Ladakhi greeting) are exchanged, bowls and cutlery taken from the shelves, and copious amounts of rice and dahl scooped onto plates. Monks, Spanish hipsters, and French students all sit down to enjoy the meal and a giggle at the end of another day. The 31 monks of Matho have been sharing their kitchen and kindness like this for five years now, as art historians, architects, museum specialists, and conservationists from all over the world flock to their monastery for nine months of the year. Joining forces, this colorful ensemble is the engine behind the Matho Museum Project—one of the most exciting ventures in Buddhist art preservation today.

A treasure trove

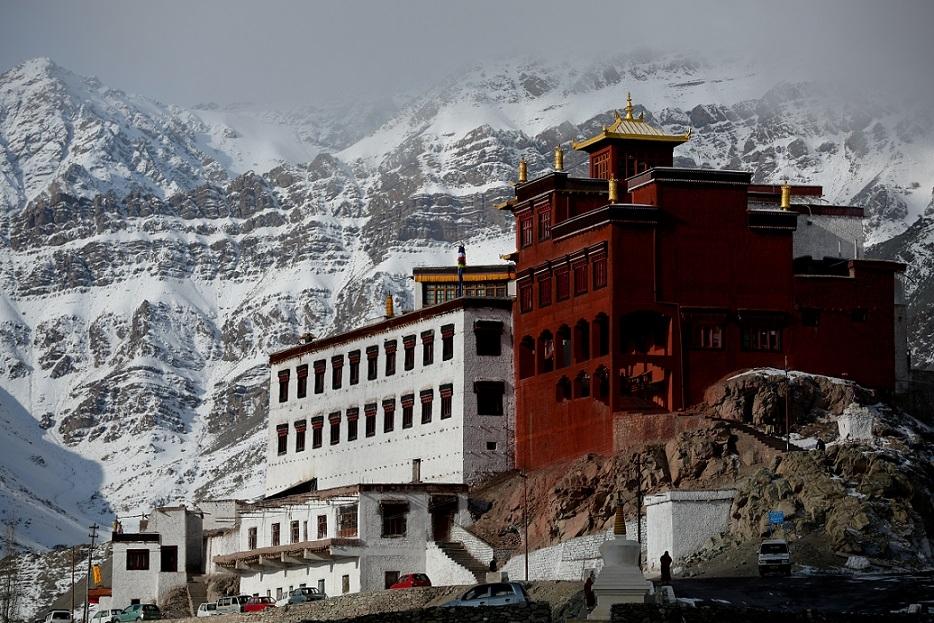

Matho Monastery is tucked away among the snow-capped peaks of Ladakh, the Land of High Passes, in northern India. It is the only monastery of the Sakya order of Himalayan Buddhism in Ladakh. Ever since the monastery’s inception in 1410, its residents have commissioned and collected art objects: precious thangkas painted on cloth, exquisitely carved ivories, and svelte Kashmiri bronzes, many of which predate the monastery itself. While the collection grew through the centuries, it also decayed. Covered in years of soot from oil lamps, thangkas became unrecognizable, were placed in boxes, and gradually, fell into disuse.

From Nelly Rieuf

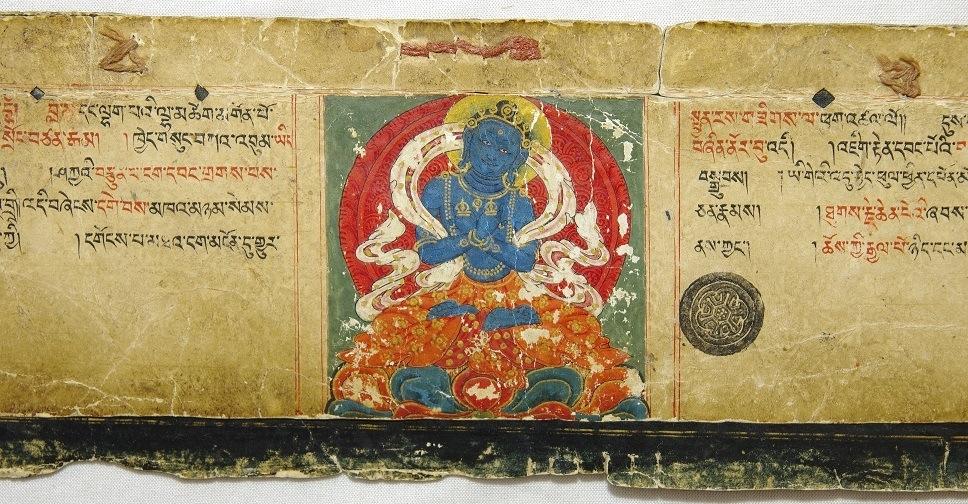

That is, until 2009, when H. E. Gyana Vajra Rinpoche, one of the sons of H. H. Sakya Trizin, reached out to the Himalayan-art restorer Nelly Rieuf, having seen her work in Nepal’s Upper Mustang region. At his request, Nelly arrived at Matho Monastery one crisp January morning in 2011 and was presented with a number of heavy boxes. The seals broken, they revealed some very fine works of art. But this was only the beginning. As the monks led her through the maze of dark rooms and corridors, other treasures presented themselves: ritual masks, tiger-skin clothing, ancient manuscripts and wall paintings.

The size (over 2,000 objects) and variety of the collection were astonishing—it ranges in time from the 9th century to the present day and incorporates artistic styles from Kashmir, Nepal, Tibet, and China. What united all the objects, however, was their urgent need of some tender loving care. Dust and soot had made Manjushri indistinguishable from Avalokiteshvara, animal masks were missing teeth or eyes, and the once-vibrant silks had lost their luster.

A museum was the obvious answer to the monks’ desire to preserve the collection and share its beauty with the public. Over the next few years, Nelly set out to bring together monks, specialists, and volunteers to realize this ambitious vision: a celebration of Buddhist art and culture in the highest museum in the world.

Heritage cannot wait

We do not need to see the news reports of the devastating earthquakes in Nepal or the destruction of ancient Assyrian artifacts by ISIS militants, or read about Palmyra treasures ending up in London galleries, to be reminded of the fact that heritage cannot wait. In the Himalayas, even without the ever-present dangers of looting, conflict, and natural disaster, the inevitable passing of time can lead to neglect.

Himalayan Buddhism is prevalent in only a handful of places: Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, and Ladakh. In these places, too, the lure of modern life and the homogenizing effects of globalization are seeping into homes through television. The glitz and glamour of jeans and sneakers mean the winds of change are blowing: fewer people join monastic orders or stay in touch with ancestral traditions.

Children from Matho Village go to university in Chandigarh or Srinagar after completing their schooling; their world is so much larger than that of their parents and grandparents. The flipside is that young ones simply cannot dedicate as much time to the upkeep of traditions, and neglect of cultural heritage can ensue.

Yet in a world where boundaries blur, where everyone sings along to the same pop songs, these traditions are ever more important: they bind a person to a particular place and time, providing a sense of belonging and identity in a world in flux. Art objects like those at Matho Monastery are the material reminders of a shared history and can serve as the foundation for a shared future. When heritage starts to unravel, so, too, can the cultural cohesion that binds a community together. But art doesn’t exist or survive on its own. Both its creation and its continued existence are the fruit of human effort and creativity, and sometimes a helping hand is needed.

A monastery museum

The Matho Monastery Museum, or MaMoMu, is being built within the monastery compound, overlooking the spectacular mountains and lush valley. It is due to open its doors in the spring of 2016 and will showcase a true treasure trove of Himalayan Buddhist art. Forget about whitewashed walls and bright lights—the deep purples, rich golds, subdued lighting, and atmosphere of this monastery museum effect a resemblance to a temple. The pillars, carved with love by local carpenters from the poplars in the valley, support a structure that is built using only traditional techniques and renewable materials: the trees and earth of Matho. The ancient mud brick technique is also durable and earthquake resilient, and blends harmoniously with the monastic buildings.

This carefully designed setting emphasizes the dual nature of the monastery museum as both a display of admirable works of art and a temple where the divinity that resides in the objects can be venerated. This same principle guides the conservation work: artifacts are restored not only to enhance their aesthetic quality, but also to render them once more suited to their role as vehicles of the Buddhist pantheon.

The monastic museum will consist of three floors covering a total of 470 square meters and showcasing 12 centuries of artistic output. Each floor has its own focus: on the first floor, the visitor is taken on a time-traveler’s journey into the past and introduced to the origin of styles and the virtuosity of early masters. The second floor has an iconographic focus as the visitor encounters a “Who’s Who” of Buddhas, bodhisattvas, deities, and lamas and receives a crash course in Buddhist philosophy. The third floor is reserved for the mystery of powerful Buddhist rituals, dance, and music, as well as the monastery’s history.

A holistic model of cultural management

The Matho Museum Project is made up of an eclectic mix of enthusiasts. Center stage is taken by the men in red, the monks of Matho. Not only did they initiate the project, they are always at hand to explain to the layperson the principles of Buddhist philosophy. The construction site is a hive of the finest Ladakhi masons and carpenters, cutting wood and mixing mortar. Local women and men, their heads wrapped in scarves to protect them from dust and the scorching sun, are complemented by students and professionals who freely offer their time and labor. Romain, for example, a French architect, can be seen discussing the building plans with the foreman, Gurmet. Gurmet’s sister, the local art dentist, is providing the ritual bear mask with a proper set of incisors. She’s part of the Matho Village Sisterhood of Extraordinary Conservationists, 16 ladies trained for five years by Nelly in the art of restoration, who staff the workshop and work tirelessly to bring the collection back to life. They’ve learnt all about the properties of colors and chemicals, drawing techniques, manuscript conservation, and so on. With this unique set of skills, these women are at the vanguard of cultural heritage protection in the region.

This wonderful collaboration between local and international experts has resulted in a holistic model of cultural heritage management that truly broadens horizons. Nelly is endeavoring to spread this model in Ladakh’s fertile ground. Many Buddhist monasteries have locked their collections away in order to prevent looting, thus inhibiting the use of the objects for rituals and aesthetic enjoyment. By raising awareness of the importance and value of cultural heritage and facilitating the exchange of knowledge, the Matho Museum Project is enabling the rehabilitation of the artistic output of Ladakh, whose beauty and wisdom as part of our universal human heritage surely deserve to be celebrated.

Click here to watch a video showing a model of the monastery and museum.

Nathalie Paarlberg worked for the Matho Museum Project in the summer of 2014. She is currently completing her MPhil in Asian Studies at Leiden University in the Netherlands.

See more

The Matho Museum Project (website)

The Matho Museum Project (Facebook)