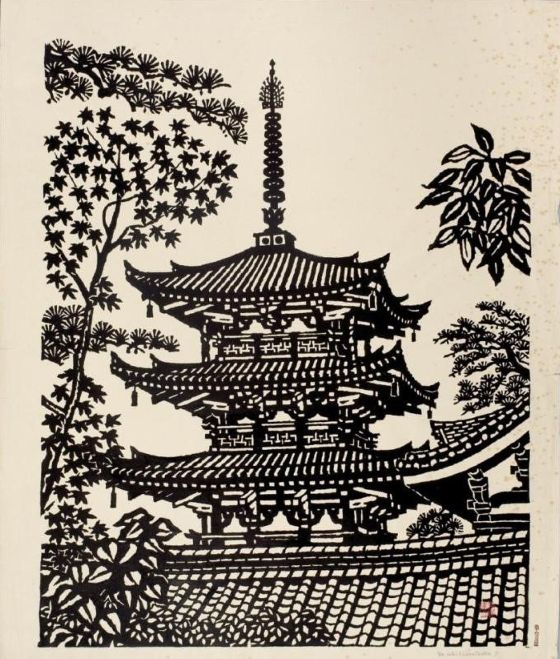

Woodblock print, 31-7/8 x 26-3/4 inches. Honolulu Museum of Art, gift of James A. Michener.

Image courtesy of the family of Un’ichi Hiratsuka

Built around 700 CE, the pagoda at the Horyu-ji, a Buddhist temple near Nara, Japan, is one of the world’s oldest wooden buildings and one of the most important structures in early Japanese Buddhism. It was founded by the Imperial Prince Shotoku, who embraced this foreign faith. Though rendered only in black lines on a white ground, the print beautifully conveys the architectural details of this sacred building, from the even, rhythmic patterning of the ceramic roof tiles to the elaborate wooden bracketing that holds up the heavy roofs and the carved railings that encircle each of the stories. It also expresses the monumentality of the pagoda, showing it rising up from behind the Main Hall or Kondo, framed by maple, pine, and other trees in the temple complex.

The print was created by Hiratsuka Un-ichi (1895–1997), one of the founders of the Japanese “creative print” (Jap: sosaku-hanga) movement that began in the early 20th century. This movement encouraged artists to design, carve out, and print their own images in a radical shift from the traditional Japanese printmaking process, in which the publisher commissioned artists to design prints and then hired block carvers and printers to produce them. Like the movement’s co-founder Onchi Koshiro (1891–1955), Hiratsuka studied Western painting and printmaking, but while Ochi’s print and book designs are largely inspired by international modernism, many of Hiratsuka’s designs echo the aesthetics and subjects of the early Japanese Buddhist prints that he collected for many years. Although his artistic output was vast and varied, his images of Buddhist buildings, temple grounds, and symbols of Buddhist belief are among his most evocative, recalling deep connections to his own cultural and artistic past.

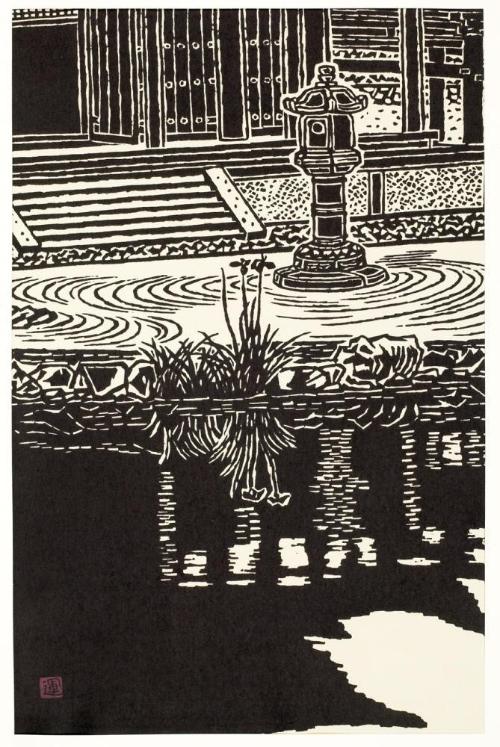

Woodblock print, 18-5/8 × 13 inches. Honolulu Museum of Art, gift of Felix Juda.

Image courtesy of the family of Un’ichi Hiratsuka

Hiratsuka was born in Matsue in Shimane Prefecture on the Japan Sea coast in 1895. The son of a shrine carpenter and the grandson of an architect, he learned to work with wood at a very young age. In the 1910s, he studied painting and printing in Tokyo. There Hiratsuka learned traditional Japanese woodblock print carving under Bonkotsu Igami, who was trained in the block carving used in ukiyo-e style prints of beautiful women, kabuki actors, and landscapes. This training grounded him well in block carving techniques. He had his first exhibition of prints in 1916, and by the 1920s was already a very well-respected woodblock print artist, later going on to teach another renowned sosaku-hanga artist Munakata Shiko (1903–75). Between 1935 and 1944, Hiratsuka taught the first-ever class in woodblock printing in the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, elevating the status of woodblock printing to a fine art at a time when many artists had rejected traditional Japanese artistic techniques in favor of Western ones. Hiratsuka moved to Washington, DC, in 1962, where he taught woodblock printing, exhibited and sold prints, and was commissioned by three standing presidents to carve woodblock prints of national landmarks, including the Lincoln Memorial, the Washington Monument, and the Library of Congress. Hiratsuka was awarded the Order of Cultural Merit by the Japanese government in 1970, and in 1991 the Hiratsuka Unichi Print Museum was opened in Suzaka, Nagano. He returned to Japan in 1994 and died a few years later at the age of 102.

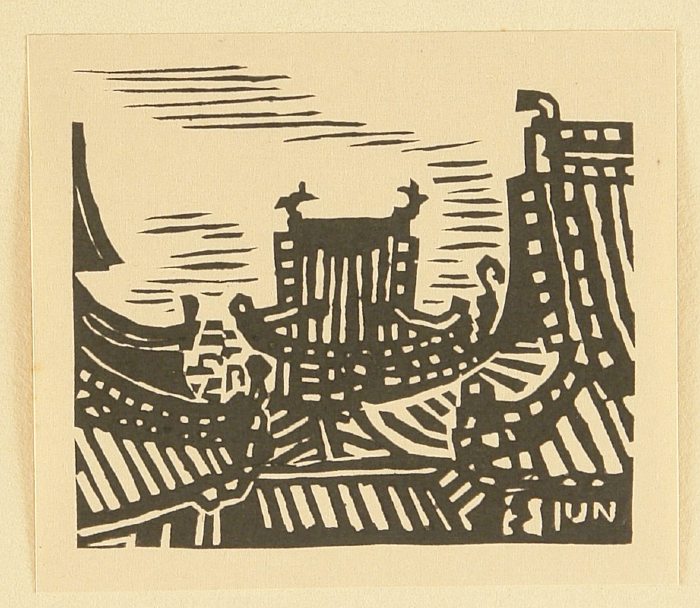

Over his long artistic career in Japan and the US, Hiratsuka created many designs of landscapes, buildings, and natural motifs. Prior to World War II, he created both full-color and monochrome woodblock prints and engravings, but after the war, he worked almost exclusively on black-and-white prints, incorporating his famous technique tsukibori (“poking strokes”), in which he rocked the blade of his small square-end chisel from side to side in short strokes to create rough and jagged edges, clearly visible in works such as his 1938 print Temple Roofs shown above. Hiratsuka believed that the combination of black and white had a special and challenging beauty since the artist only had these two colors with which to capture the rhythm of line and mass, which he does with exceptional skill in prints such as Lakeside at the Byodoin. Echoing a concept familiar to Zen Buddhist artists, he taught that white was not merely negative space but had a value equal to the black inked space, and that each color had to harmonize with the other. In Oliver Statler’s book, Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn (Charles E. Tuttle Company 1956, 37), Hiratsuka explained: “One of the great difficulties is to make the white space live. . . . The handling of white space is different in every one of my pictures.”

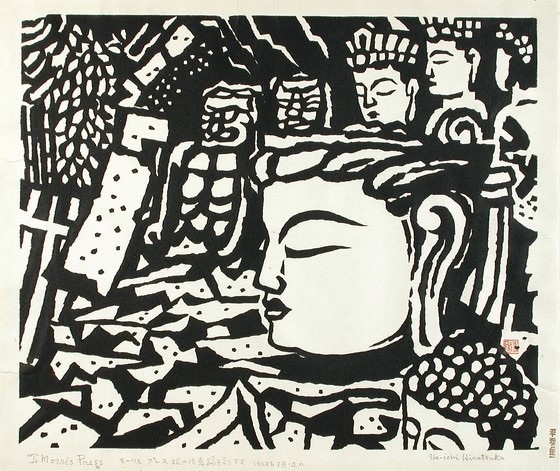

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Morris Press.

Image courtesy of the family of Un’ichi Hiratsuka

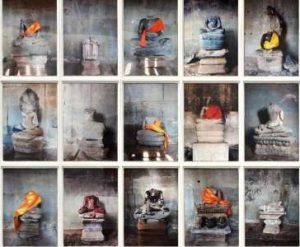

In one of his most striking monochrome prints, Stone Buddha at Usuki, Hiratsuki’s mastery of the balance and harmony of black and white are clearly apparent. The image depicts a group of stone Buddhist statues created in the Heian period (794–1185) at Usuki on the Kunisaki Peninsula of Oita Prefecture in Kyushu. Over the years, weather and neglect had worn down the statues and, most famously, the head had fallen off the main statue of Vairocana, the Cosmic Buddha (Japanese: Dainichi) and it rested on the ground for hundreds of years (until it was restored in 1993). Here, Hiratsuka renders the toppled head of the Buddha with reverence, placing it at the center of the image, flanked by the other deities and using plentiful white space to illuminate the serene face within bold black lines.

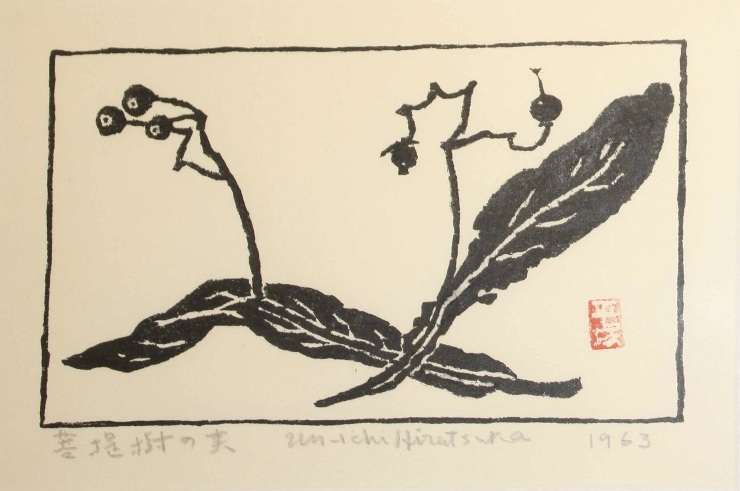

In a small botanical print in the collection of Scripps College in Claremont, California, we see his range as an artist and his continued fascination with Buddhist symbols and motifs. In this simple monochrome print, he depicts the leaves and fruit of the Bodhi tree, or Ficus religiosa (sacred fig), the tree under which the Buddha attained enlightenment In Bodh Gaya, India, some 2,500 years ago. Wood from the Bodhi tree and its descendants is often made into Buddhist prayer beads or mala, and its heart-shaped leaves are dried and their skeletons used as a ground for painting. For centuries, disciples of the Buddha have planted seeds from the Bodhi tree and its descendants at Buddhist centers around the world. Hiratsuka was no doubt aware of the connection between the spreading of the seeds of a tree and the spreading of a spiritual tradition. The print was made in 1963, just a year after Hiratsuka moved to the US and began to share his woodblock printed art with a new audience in the West. Whether consciously or subconsciously, he may well have been hoping to share the spirit that informed much of his art too.