The chuka-chuka-chuk sound of wood scraping on metal resonates rhythmically through the room like a musical salt shaker as Geshe Kunchok leans over the vividly colored board delicately guiding the final grains of colored sand into the border section of the sacred pattern below him. An audience is gathered around him and has been watching in awe—sometimes chatting, mostly silent—as he and two other monks dressed in saffron- and wine-colored robes have almost magically transformed a blank wooden board into a spectacular Buddhist mandala.

Three monks have spent three full days pouring brightly colored grains of sand through the slender conical brass funnels called chak pur, coaxing the sand onto the board by rubbing a wooden stick along ridges on the side of the funnel. Geshe Kunchok’s face is just inches from the board and as he disperses the final grains of black sand into the outer border of the circle. He exhales a barely audible “yeh” and sits back wearing an expression of satisfaction. The mandala is finished. Everyone in the room claps and cheers—in amazement and also relief. The experience of watching them make this sand mandala has been at once meditative and extremely intense.

Sand mandalas are a particularly powerful type of mandala—the elaborate cosmological diagrams that represents the enlightened realm of a Buddhist deity. They are constructed using millions of particles of sand that symbolize the potential for all beings to live together in harmony and peace if we all create more space for each other in our hearts. It is said that when a sand mandala is created, all sentient beings and the surrounding environment are blessed. And after the mandala is created, it is destroyed in a dissolution ceremony that serves as a reminder of the impermanence of all compounded phenomena.

This particular mandala represents the enlightened realm of the Buddha of Compassion, the deity Avalokiteshvara (known in Chinese as Guanyin and in Japanese as Kannon). Avalokiteshvara is considered the most compassionate of all Buddhist deities, having sworn to postpone his own enlightenment until all sentient beings have become enlightened. The purpose of the construction of this particular mandala is to encourage us all to generate a compassionate heart for the benefit of all sentient beings.

The group of monks who created this sand mandala traveled to Pasadena, California, from Ladakh and Nepal as part of their 2018 Great Compassion Mandala Tour of the United States to raise awareness and funding to support the Ngari Institute of Buddhist Dialectics in the Himalayan region of Ladakh. An Indian NGO dedicated to the preservation of Tibetan Buddhist culture in Ladakh, the Ngari Institute was founded in 1979 by the Ladakhi alumni of the Sera Jey Monastery in southern India.

From 2006, the institute has run a school for local children in a small village called Saboo near Leh, the capital of the former kingdom of Ladakh. Created to empower and enrich poor and needy students in this remote area of northern India, the school imparts a combined learning of both modern scientific knowledge and ancient Buddhist wisdom, specifically teachings of the Tibetan Gelugpa lineage. Earlier this year, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, head of the Gelugpa lineage, visited the institute to offer blessings and support—a moment of great celebration for all present.

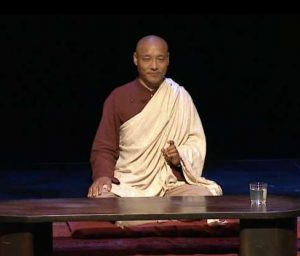

Currently 60 children aged 4–18 attend the Ngari Institute, many of them orphans and some from single-parent families who cannot afford to feed them. Alongside a modern curriculum of languages, mathematics, and science, they learn ancient philosophical and spiritual teachings including yoga, meditation, and the Buddhadharma. A small Buddhist temple is part of the institute, and from here the current president, Geshe Tsewang Dorje, and the rest of the temple’s sangha oversee the Ngari Institute and offer Buddhist teachings to the children and the local community.

Geshe Tsewang, who was also one of the founders of the institute, looks to the international community to help his local community and uses the sand mandala as a tool for spreading compassion and encouraging support. To him, the Great Compassion Mandala Tour serves several purposes. “First, we want to share the Buddha’s message of peace and compassion through the mandalas,” he explains. “Second, we wish to create an international network of places and friends. And finally, we want to fundraise for the children in their school to provide education and meals for them.”

As the monks travel to various sites, they invite local visitors to watch them create the mandala, teach them about this sacred Buddhist art form and explain how their work benefits the students of their school. For example, it only takes a donation of US$540 to help put a child through the school for a year—and another US$180 for a year’s worth of food.

Geshe Tsewang Dorje and his fellow monks, Geshe Kunchok, Geshe Jampa, and Lama Kunkhen, prepare the mandala for the dissolution ceremony two days after its completion by lifting it onto a table and surrounding it with seated figures of the Buddha, flowers, candles, and silk ceremonial khata scarves. They thank all those visitors who have come to watch the making of the mandala. In the Buddhist tradition, the act of creating a sacred image is good karma that help us all attain spiritual merit and a higher rebirth, and supporting those who create these sacred images also accrues merit.

Most of the visitors who lingered in the room where the mandala was being made were not Buddhists, and many were seeing a sand mandala being made for the first time. Yet it was clear to all present that there was a special power emanating from this sacred work of art—not only the energy often apparent in expressions of devotion to an ancient spiritual teaching, but also the deeply compassionate power created by traveling across the world to use that teaching and its artistic expression to help those less fortunate back home have a better life.