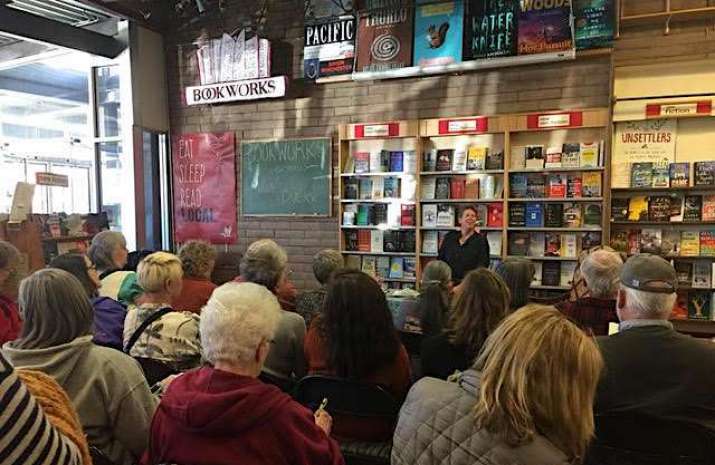

Maia Duerr has worked as a qualitative researcher, an anthropologist, a writer, and an editor. She served as the research director of the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society (CMIND) from 2002–04 and as the executive director of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship from 2004–07. In 2010, she wrote an introduction to engaged Buddhism for the PBS movie The Buddha, and launched a blog called the Liberated Life Project that same year. This past December she released the book, Work that Matters: Create a Livelihood That Reflects Your Core Intention (Parallax Press, 2017). This month we interviewed Maia about her life and her new book.

Buddhistdoor Global: You have lived a unique and interesting life, but one that is in a way quintessentially American: a fair amount of geographic mobility; some of it for jobs, some for dreams and pleasure. Can you say a little about how you got to where you are today?

Maia Duerr: I’ve spent most of my adult life on a search for work that I could fall in love with. As I share in the first chapter of the book, I remember being a kid and every night when my father came home from work, witnessing his job-related misery and depression. I’d watch him, with my heart breaking, and think to myself how can my life be different from that? How can I feel great about what I do for work, not just try to get through it and live for the weekend? So I experimented a lot with how to do this. I tried at least four different careers (mental health professional, cultural anthropologist, nonprofit professional, writer/editor) and countless jobs within those careers. In the last 10 years, as I’ve brought my meditation practice into the equation, I’ve learned so much about how to create work that I love—and that’s what I want to share with others in this book.

BDG: In your book, you write about your mother’s advice to you when you were young to have a fallback plan as a secretary. You write that you could see that this came from a good place, but it also put shackles on you as you moved forward. Do you think Buddhist practice and philosophy has helped you see this more clearly and work with it?

MD: Oh, absolutely! My meditation practice and, underlying that, my understanding of Dharma teachings has helped a great deal for identifying my own “habit energies” (as Ven. Thich Nhat Hanh would call them). Developing my metacognitive capacity to see what and how I am “thinking” has been a key ingredient in liberating myself from some of those old patterns (or at least be on the way to liberation!)

I think that training as a cultural anthropologist has also helped me to notice the cultural conditioning that has shaped how I see the world as well as “work”—including the gender and class conditioning that I described getting downloaded from my mom. As I noted in the book, my mom grew up during the Great Depression, and as I’ve learned more about the importance of the cultural milieus we live in—in her case, what it meant to be a woman and someone from a working-class family during the 1930s and 40s—I’ve developed more compassion for her and myself. And compassion is the ground that’s necessary for transformation. I’ve tried to weave those strands of wisdom and practice into the book and invite the reader to engage in those inquiries about their own lives as well.

BDG: You write of mindfulness helping people make “a shift at a deeper level . . .” in their lives and relationships to work. How does that work?

MD: During my long career odyssey in search of work that I could love, I read lots of books, like What Color is Your Parachute, religiously did all the exercises in them, took aptitude tests, and worked with a career counselor. Those things helped to a certain degree but something still wasn’t clicking for me. My pattern was to leave a job when it got frustrating and feel excited to start a new one, for a while . . . and then I’d run into the same frustrations over again, just in new ways.

About 10 years ago, my life had a total meltdown . . . an unexpected loss of a relationship came around the same time as an unexpected job layoff. Both were very painful, but what came out of that time was a more intentional relationship with myself. I started to draw on my longtime meditation practice to really look at what I was doing on all levels of my life, including my livelihood. I applied those insights from my practice to my work life, and gradually began to transform it so that now there is much more alignment between what I feel I’m here on the planet to do—what I call my core intention—and what I actually do for work each day.

BDG: Speaking of your work each day, a concern about mindfulness in work environments is that it will simply make people more pliant and willing to put up with stressful and poor environments. What has your experience been?

MD: Mindfulness certainly can be co-opted in that way, or at least there’s an attempt to co-opt it which we often see in mainstream media explications of “the mindfulness movement.” The interesting thing is that mindfulness practice is such a powerful catalyst that there is really no way to control the genie that comes out of the bottle when people start to practice. Corporations may offer mindfulness practice groups, thinking that it will help employees to “calm down” and simply do their jobs in a more productive way, but the result may be that an employee actually does start to question why she or he is working to create a product that may be at odds with her or his values, and then makes a decision to leave the company. When I was research director at the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society years ago, I heard stories like that.

BDG: That’s amazing! Are their ways of teaching mindfulness that can ensure that it leads to these kinds of outcomes?

MD: This is such a huge discussion now, as you know, Justin. I think one way to ensure that mindfulness doesn’t become a tool of capitalism is to contextualize it within the rest of the Eightfold Path that the Buddha taught, and to remember it was never intended as a standalone. Of course, there are all kinds of dialogues about that these days, secular versus religious, and all that. In some ways I think that’s a red herring that distracts us from the essential point, which is how can we live ethically in relationship to each other and this planet? One doesn’t need to be a card-carrying Buddhist to ask and explore that question, and it feels to me like the key question of our times.

BDG: This sounds like something you have spent a good amount of time thinking about. And of course, we’ve only just scratched the surface here. Aside from your new book, in closing, do you have any recommendations for readers to dig deeper?

Readers might appreciate an article I wrote a few years ago, beginning to tackle the issue of mindfulness, work, and ethics: “Socially Responsible Mindfulness,” which includes some great insights from Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi.*

* A Socially Responsible Mindfulness

See More

Work That Matters: Create a Livelihood That Reflects Your Core Intention (Parallax Press)

An Introduction to Engaged Buddhism (PBS)