Nestled behind adobe walls in the shady hills of Montecito, a wealthy community next to Santa Barbara, California, is Ganna Walska’sLotusland. The 37-acre (15-hectare) botanical garden, which has been open to the public for the last 25 years, is home to many diverse traditions—both horticultural and spiritual—that have taken root in this beautiful southern California space. Named for a flower of exquisite beauty and profound spiritual significance in Buddhism, Lotuslandreflects the many aspects of its founder, Ganna Walska, a fascinating woman whose earlier life was full of high-society glamour and riches but who in her final decades devoted her time, wealth, and energy to cultivating a legacy of natural beauty, fantasy, and spirituality.

Born in Poland in 1887, Walska lived a colorful life, performing in Europe and the United States as an opera singer, marrying six very different men, and penning her autobiography Always Room at the Top, in which she reminisced about the first 50 years of her life as a glamorous socialite, hobnobbing with royalty, Charlie Chaplin, and other great figures from the literary, theatrical, musical, artistic, and diplomatic worlds. In 1941, at the suggestion of Theos Bernard, her last husband and an eminent and well-traveled scholar of yoga and Tibetan Buddhism, she purchased the Cuesta Linda estate in Santa Barbara. Intending to transform the estate into a retreat for Tibetan monks, they named it Tibetland. However, Walska’s marriage to Bernard quickly dissolved and the Tibetan monks never appeared. After this final marriage, Walska changed the name of her estate to Lotusland in honor of the sacred Indian lotus growing in one of the pools on the property and devoted the remainder of her long life to building her garden and securing its future.

Image courtesy of Ganna Walska Lotusland

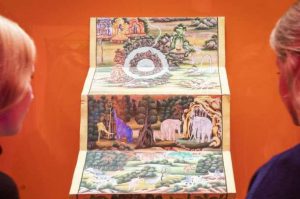

For the next 40-plus years, Walska poured her time, energy, and resources into creating a botanical garden that not only presented rare plants in a beautiful natural setting but also incorporated elements of fantasy and spirituality. Over the years, she worked with a number of landscape architects as the “head gardener” to realize her vision, massing many species of plants together—often paying top price to obtain rare plants and auctioning off some of her jewelry to finance the renowned Cycad Garden. Among the main features of the garden are areas dedicated to aloes, bromeliads, cycads, ferns, succulents, cacti, and euphorbias, butterflies, and the color blue. Alongside the rare and exquisite plants with which Walska filled the garden, visitors to Lotusland can also see many details that reflect her playful, dramatic personality. Walska loved colored glass and clamshells, and used them to decorate fountains and create borders along paths as if fairies had scattered precious gems throughout the garden. In her Topiary Garden, large topiaries surround a 25-foot (7.6-meter) working floral clock, with each hour signified by a copper zodiac sign set in plantings of succulents and colored stones. A fountain close to the main house is embellished with Delft ceramic tiles and an elaborate bronze spout in the shape of a mythical aquatic creature.

The spiritual heart of the garden is arguably the Japanese Garden, the largest of the individual gardens and originally created in the 1960s, it is currently undergoing renovation due to be completed in spring 2019. Walska worked with local stonemason Oswald da Ros and Frank Fujii, a Japanese garden designer and aesthetic pruner. Fujii, who had built a few Japanese-style gardens in the area, including one for a Buddhist church, became the lead gardener for this project and his insistence on simplicity in this garden balanced Walska’s tendencies for the dramatic. According to Fujii, the creation “gives you a feeling when you walk through the garden . . . of serenity, quietness. Makes you feel you want to meditate.”

Image courtesy of Ganna Walska Lotusland

The Japanese Garden includes many Buddhist elements, including winding paths and stepping stones, which encourage visitors to focus the mind and walk mindfully through the natural environment. At one point along the path, visitors will encounter an old stone statue of a Buddha sitting in serene meditation beneath a Japanese maple. Also placed around the garden, sometimes lining the pond, sometimes hidden away behind bushes, are Japanese stone lanterns, several of which Walska purchased from private estates in Montecito when the garden was originally being built. For decades now, they have stood silently, symbolically illuminating the garden for visitors passing through the space.

When Walska first visited California in 1923, she had already begun to study Eastern spirituality and wrote in her memoir that here, “the air is magnetized, the consciousness awakens.” When she bought the estate in 1941, she and Theos Bernard had planned to make it a Buddhist retreat. Twenty years later, as she worked with Fujii to create the Japanese Garden, her goal was unlike those of many wealthy Westerners who built Japanese gardens on their estates. She was not merely attracted to their beauty and exoticism, but had a deeper understanding of the garden’s spiritual qualities. She is known to have said, “It is fundamental that if you will provide the soil, the flower will bloom. So it is with the heart of man. Once the environment is found, the soul will release its perfume in all the creative channels . . .” Having named her botanical legacy Lotusland, she clearly recognized the importance of not only nurturing plants and flowers but also one’s own spiritual growth, and believed that anyone—even a bejeweled Polish opera singer and socialite—can aspire to spiritual enlightenment.

See more