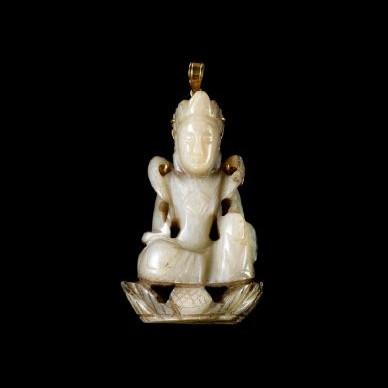

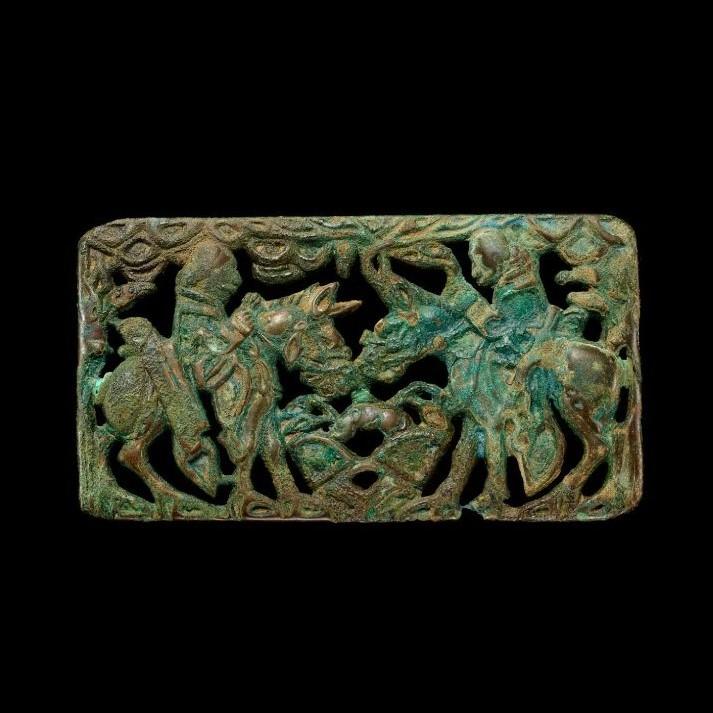

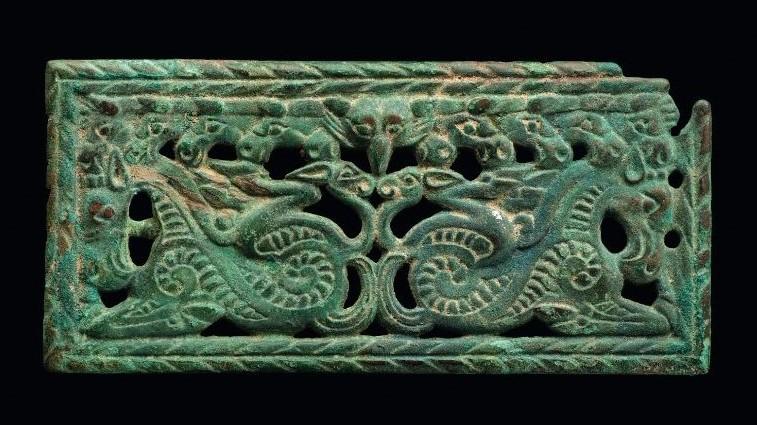

Mengdiexuan Collection. Image courtesy of the Indra and Harry Banga Gallery

Art has been around almost as long as humanity itself. Art reflects the depths and richness of the human psyche in visual form. The cave paintings of the Grotte de Lascaux in France, depicting flora and fauna harvested and hunted by Paleolithic humans, speak to something primal yet timeless and universal in us. They would have been similar to the animals and plants encountered by the Orochen, the last hunters of China’s northern forests. The world of the Orochen is one of fur leggings, birch bark boxes and saddle bags, and deerskin pouches. Majestic antlers, powerful hooves, and soulful eyes of deer suffuse the lives of these communities of nature, just as deer and other animals touched the innermost vulnerabilities and primeval awe felt by the Lascaux painters. Bears, horses, saddles, fur—the folk memories of hunting, riding, slaying, and fighting can be found in so many patterns and designs of everyday scenery as well as in surprisingly abstract forms.

In Hong Kong, the Indra and Harry Banga Gallery at City University is running an exhibition titled “Hunters, Warriors, Spirits: Nomadic Art of North China” from 23 July–23 October. It has six main sections: “Land and People,” “Hunters and Animals,” “The Early Nomads—Xianbei and Xiongnu,” “Warriors,” “Empire” and “The Spiritual World.” The gallery, which opened in 2016, is eclectic in its portfolio of exhibits. Until recently it was under the direction of consulting curator Dr. Isabelle Frank, who took me on a tour of this exhibition in September. She emphasized how the nomadic peoples of Central Eurasia had an extremely complex and ancient relationship with the sedentary “peripheral empires.” These are the better-known societies of China, Persia, Rome, and others that, until recently, occupied the dominant historical narrative.

This exhibition goes some way to highlight how the role played by the nomadic peoples shaped the history of China and that of Greater Eurasia. It tells the story of the nomadic heritage from the early first millennium BCE to their “golden age” between the 10th and 13th centuries CE. The array of belt plaques, buckles, swords, stirrups, and many more items are on loan and from two main collections: the Mengdiexuan Collection, and the Hing Chao Collection. The latter is the private collection of businessman and cultural icon Hing Chao, who also served as the exhibition’s chief curator. But it retains a flavor of the contemporary through the sculptures of Dashi Namdakov, a Russian artist with nomad roots. His striking art is placed in aesthetically matching areas throughout the gallery. They complement each of the six sections or themes, and, while being eclectic and anachronistic, exude a kind of imaginative self-understanding. Semi-fantastical and dynamic, the aesthetic vibrates with energy and power informed by past and present.

While also executive chairman of Hong Kong-based Wah Kwong Transport Holdings, the curator, Chao, has balanced his corporate leadership identity with that of a prominent aficionado in Hong Kong’s cultural world. He is a promoter of Chinese martial arts, executive director of the International Guoshu Association, founder of the Hong Kong Culture Festival, and chairman of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Earthpulse Society. He is well known for having spent time among the Orochen and is among the most well-informed Hongkongers about the nomadic communities of the far north.

Chao states about the exhibition’s intent:

In this exhibition we try to provide alternative viewpoints on how we look at the nomads and Chinese history in general. This involves an anthropological approach that we call “emic,” which is trying to understand things from the local or indigenous people’s points of view. We have done this by integrating contemporary anthropological research, but also adapting this research and sensibilities when interpreting ancient nomadic artworks on the premise that, in fundamental ways, there is continuity in the historical evolution of nomadic culture in North China. And what we want to show is that the nomads, or more precisely the interactions between the nomads and the Chinese state, and the Han, are the very fulcrum upon which Chinese history and culture turned.

It is difficult to undo the confusion done by traditional categories imposed, with good intentions, on artistic traditions that cannot be corseted by such rigid definitions. Dr. Frank also notes that art history divided art into categories such as “decorative arts” versus “fine arts”—a useless classification when applied to most art around the world. A different, but related, problem is the word “shaman” or “shamanic” applied to the incredibly diverse spiritual ideas of the Central Eurasian or nomadic peoples. Chao says:

First of all, it is important to note that the word shamanism is derived from “shaman,” which is a Tungusic word that came from North China. In many ways, the territory encompassing North China [particularly, Inner Mongolia and the Northeast], Mongolia, and East Siberia, and perhaps parts of Inner Asia, are what we consider to be the ‘homeland’ of shamanism. The cultures of this easy region are interconnected, so while the specific rituals and beliefs among each group might differ, we can more or less speak of a common shamanist tradition in North Asia. Shamanism is an animist faith, so it is strongest where people live close to nature. It makes sense that shamanism is particularly strong among the nomads, but it also exists among semi-nomadic and some sedentary populations.

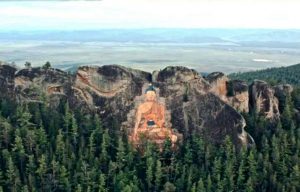

“Shamanism” was undoubtedly a more prominent presence in parts of Eastern Europe, particularly in the Pontic-Caspian steppe around the Black Sea. Most of these lands were eventually Christianized, although some nomads in certain areas converted to Islam. Yet many of the nomadic groups, such as the Xianbei peoples that formed the Northern Wei (386–535) and Northern Qi (550–577), and the Khitans that founded the Liao dynasty (916–1125) (the Liao era features prominently at this exhibition), considered themselves patrons and believers of Buddhism. Chao has his own take on why nomads, upon encountering Buddhism along the Silk Road and in China during the medieval period, heartily embraced the Dharma.

Unlike Buddhism, both Christianity and Islam are less tolerant of other beliefs, so shamanism has more or less disappeared in these places. Historically, however, shamanism was undoubtedly strong in these areas, definitely during the Age of Migration, which was related to the movement of the nomads from Asia to Europe, up until probably the 13th–14th centuries, when Mongol rulers in the West converted to (mainly) Islam. Therefore, shamanism only survived in regions where the Mongols and Turks managed to maintain a traditional lifestyle, which was manly in Siberia.

The nomads had no set religious doctrine, let alone attachment to dogma. This made Buddhism an ideal “mirror” spiritually: it was an open religion and could co-exist comfortably with shamanism in ways that more exclusive traditions such as Christianity and Islam would struggle. Chao contends:

Buddhism offers solace to the nomads who lived, and still live, a harsh life, while its teachings on life and death provide a certain spiritual tranquillity; one should add that in shamanism (and in the nomads’ general worldview), death is not conceived separately from life, so Buddhism appeals and resonates with them at a deep existential level. Finally, Buddhism balances and softens the martial aspect of nomadic culture.

The exhibition demonstrates several core points: firstly, Eurasia is the geographical heart of Buddhism, and the history of this spiritual tradition is inseparable from the currents of politics, culture, and trade that have criss-crossed the continent since antiquity. Secondly, our assumptions about the idea of modern nation-states and even the notion of “peoples” is always in flux and changing. While the Xiongnu, Xianbei, and Khitans have long since disappeared, the Orochen are still around, just like the Manchus, descendants of the Jurchens. When do a people disappear, and when does another re-emerge? There are no easy answers. What we do have, however, are stories to be enjoyed and listened to . . . in swords, belt buckles, stirrups, pouches, and bags taken across the plains.

See more

New exhibition recreates nomadic art of North China (City University of Hong Kong)

Rich nomadic heritage roots of ancient Silk Road unearthed in CityU’s latest exhibition (The Value)

‘So much Chinese culture came from the outside’: nomads, the Silk Road and developments in ancient art in northern China (South China Morning Post)

Related features from BDG

The Buddha at Sea: Atlas of Maritime Buddhism and New Experiences in Museology

Related blog posts from BDG Tea House

Where the Lights of Chang’an Never Go Out: the Age of Confidence from Tang Mausoleum Murals

A Mausoleum of Marvels: Murals of the High Tang in Hong Kong