Perception is always an active construction, an inside-out, top-down neuronal fantasy in a never-ending dance of prediction and prediction-error.

Anil Seth1

Color is the place where the brain and the universe meet.

Cezanne2

I remember driving home after one of my first week-long retreats, more than 40 years ago, through a familiar spring landscape of sprawling farms and distant hills in Germany, and suddenly being hit by the beauty of it all: the brightness of the green fields and the sheer vividness and presence of the trees and buildings under the clear blue sky. It was utterly tantalizing and I wanted to drink it in more fully—look, those heavenly horses—but I wasn’t able to stop the car. The experience was a strong contributing factor for taking up a daily meditation practice, because I had a hunch that it would create the conditions for seeing through the veils of habits that normally obscure my vision, not just physically, but also on a more existential level. There was a strong pull toward exploring the intuition that there was something different to reality than usually meets the eye.

I wonder whether a similar longing to see things afresh makes us want to go on holidays. We can’t see the wallpaper of our lives anymore, everything is a little removed from experience, bland and boring. We just go through the motions of it and have the feeling that something vital has gone missing. Sometimes just a change of scenery will do the trick and we wake up from autopilot. But sometimes it doesn’t happen according to plan and even the most extraordinary landscape leaves us cold. Taking a profusion of photos and posting them on social media doesn’t cover up the fact that we can’t find that magical switch into a way of seeing that makes us feel truly alive. We long to be touched by something more meaningful than the stale stories about ourselves and the world, tinged by worry, that have been looping through our minds for too long.

Sight is the most prominent sense for most of us, and in order to recover its full potential it can be useful to also pay more attention to our other senses, in a process of a general re-tuning of our given means of perception. I held an event recently at a café/art gallery, concurrent with a show of the local G20 Art Collective of which I am part. It was titled “Looking Afresh – A Mindfulness and Art Appreciation Workshop,” and before looking at the art, we gathered around a long table and drank tea out of three little paper cups each, with three different flavors. We gave our full attention to sounds, as the coffee machine brought the water to the boil in a hissing, fuming crescendo; a dramatic, complex happening that is normally just the slightly annoying background to café conversation. We lingered with each type of beverage, savoring color, temperature, scent, and taste, like children in discovery mode, reigning in the compulsion to simply identify, label, and be done with it. What was it like, paying attention in this way? The ensuing conversation brought some qualities of mindfulness into conscious focus: curiosity, openness, absorption, slowing down, appreciation, being in the moment, and freedom from judgement were mentioned.

For some of us, the curiosity extended to questioning the assumed reality of the perceived object, in this case, three types of herb tea, and to the relationship between appearances and consciousness. Is there a substance out there called rosehip tea that would look, smell, and taste the same to different people, a wasp, and a dog? Very likely not. A dog, for example, has a very different color perception to us, dichromatic, rather than trichromatic, and what is red to us, would look yellowish-green to him. A dog is also able to have an ongoing experience of smell, not limited, as it is for us humans, to the inbreath, because the structure of his nose directs the exhalation in swirling vortices back inside. Amazingly, a dog can “work out which direction a person had walked in after smelling just five footsteps.”3 And that’s nothing special to him, simply the way he notices his world. Every species lives in a different Umwelt, the German word for perceived environment. Imagine the Umwelt of a peacock mantis shrimp, which can move its eyes independently from each other in 360-degree vision. Or that of an octopus, able to sense and explore the world without direction from a central brain.

Extending our imagination into other-than-human ways of observing and interacting with the world is one way to open us to more expansive, intuitive, and less cerebral ways of being; one way to getting a little closer to that satisfying, direct, immediate experience for which we may be longing. Getting “out of the head” is the key. After the tea-drinking exercise, we got up for a walking meditation/improvisation, and I encouraged us to walk as if we could see with our backs, or sense the warmth and vibrations of other bodies as we passed by them, as if we had some extra sensors that constantly pick up ripples in the air or water currents, like many beings have. Anchored by the touch sensations of feet on the ground, we also appreciated the soundscape we co-created with our steps on the wooden floor, with the evening traffic outside the café and the fridge providing a drone. We became active participants of a multi-art environment, playing with walking, forward and backward, stopping, walking at different speeds, letting go into we-consciousness, experiencing ourselves as part of the group. It felt easy, natural, and whole—I was surprised how readily people surrendered to a process that must have been quite strange and unusual to some of them.

While it is fairly easy to appreciate that our perception of the world out there is mediated by a particular sensory apparatus and interpreted by a brain in a particular way—generally in the service of usefulness and safety—it is perhaps less obvious that our sense of a Self is equally constructed and less constant than we like to think. The neuroscientist and author Anil Seth writes:

If certain things change slowly, sometimes the brain makes a reasonable best guess that no change is happening and so we don’t experience change. This is typically being thought about in relation to the outside world, but I think it applies probably even more so to the inner experience of being a self.

(Interalia Magazine)

Having loosened up our sense of ourselves in this playful guided walking practice, we finally turned toward the artwork, standing in front of one that called us in some way and looking at it from different viewpoints, such as from the feet, or a place above the head, or two meters behind, or from the heart. Different aspects of the artwork revealed themselves in this way. One simple suggestion had a particularly moving effect on the participants: “Look at the piece like a 10-year-old child.” It made us ask questions of the artwork we hadn’t considered before. I won’t go into all the instructions I gave (there is a recording of a similar meditation on YouTube if you are interested),4 but I’ll just mention the final one, which elicited some meaningful reflections. I asked: “What does this artwork make possible in you?”

In the final sharing, one young woman revealed that she had felt drawn to a painting that seemed incomplete to her; she was irked by it in some way, wanted to put it to rights, extend the frame, and place the objects in a way that appeared more balanced to her. After having a conversation with the artwork over a prolonged period of time, she was left with a personal message that seemed to emanate from it: “Be less perfectionist.” The workshop process stimulated in her an acceptance of the messiness of the world, how it evades control and offers mesmerizing riches if one has the eyes to see them. There is a way to look at things, through the eyes of other beings, and with the whole body, that taps into our longing for connectedness, where we see and feel seen in return, and changed in the process. I think that rediscovering this living, reciprocal relationship with the environment, akin to the animism of our ancestors, may also be a key factor in responding to the current environmental crisis, but more of that another time!

1 How your brain invents your ‘self’, TED talk (YouTube)

2 Gasquet, Joachim. 1991. What he told me – I. The motif’ – Joachim Gasquet’s Cézanne, – a Memoir with Conversations, (1897–1906). Pemberton, Christopher (trans.). 153

3 Yong, Ed. 2022. An Immense World: How Animals Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us. 19

4 Mindfully Looking at Art, a meditation guided by Ratnadevi (YouTube)

See more

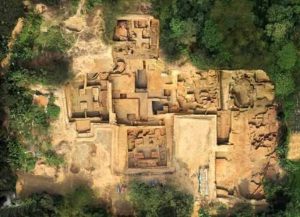

G20 Artists Collective – Tektos (The Alchemy Experiment)

On ‘Being You’ (Interalia Magazine)

Related features from BDG

Starving the Beast

How We Perceive and Are Perceived: Memory Map, the Art of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Abstract Meditations and Artistic Contemplation, with Françoise Issaly

From Bias to Balance: Liberating the Roots of Perception

Stories of the Moment: Buddhist-inspired Fiction

Perceptions and Misperceptions