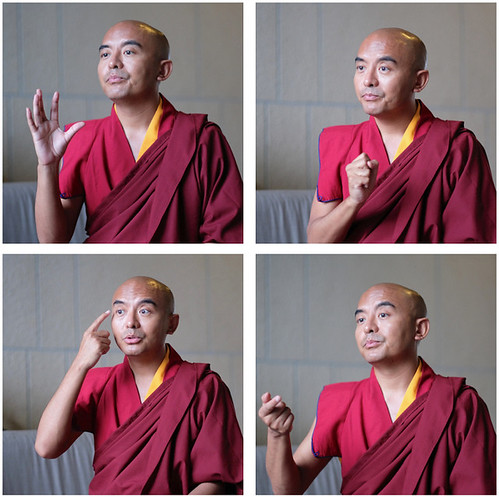

Sometimes described as the “happiest man in the world,” Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is a respected teacher and master of the Karma Kagyu and Nyingma lineages of Tibetan Buddhism, noted for his ability to present the practice of meditation in a simple and accessible manner. A vocal advocate for the profound benefits of Buddhist mindfulness meditation, Rinpoche has described how, at a young age, he was able to overcome an acute anxiety disorder through a consistent and committed meditation practice.

Born in 1975 in the Himalayan border regions between Tibet and Nepal, Mingyur Rinpoche received extensive training in the meditative and philosophical traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. He learned meditation from his father, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche (1920–96), considered one of the greatest modern Dzogchen masters, then continued his studies at Sherab Ling Monastery in northern India at the age of 11. After just two years he entered a three-year meditation retreat and then completed a second immediately afterwards, serving as retreat master. At 23, Rinpoche received full monastic ordination.

Rinpoche famously undertook a four-year solitary wandering retreat through the Himalayas from 2011–15.* In recounting how he came to terms with the realities of his ambition to practice in the manner of a wandering yogi, Rinpoche revealed some of the many personal and spiritual challenges he faced—including at one point coming to the brink of death. He describes the years spent wandering in the Himalayas as “one of the best periods of my life.”

Mingyur Rinpoche is the founder of the Tergar Meditation Community, with centers and practice groups across the world, and a best-selling writer, author of The Joy of Living: Unlocking the Secret and Science of Happiness (2007), Joyful Wisdom: Embracing Change and Finding Freedom (2009), and Turning Confusion into Clarity: A Guide to the Foundation Practices of Tibetan Buddhism (2014).

Buddhistdoor Global had the privilege of sitting down with Mingyur Rinpoche on a recent visit to Hong Kong, during which he shared some of his thoughts about life and Buddhism in the 21st century.

Buddhistdoor Global: Thank you very much for sharing your valuable time with us, Rinpoche. You’ve previously spoken in detail about the extended period of wandering retreat you undertook from 2011–15. How did your experiences then influence your personal practice?

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche: I learned many things from that experience, but there were two lessons in particular: at the beginning there was fear—strong fear—because I became sick and almost died. It was at that point that I decided just to let it flow—to allow whatever happens to happen. That has really, really helped my meditation; that’s the first. The second is I learned a lot about life and how to live. Normally, the people around me call me “rinpoche,” and wherever I go everybody treats me like that—I have my own zone that I never leave. Before the retreat, I had never stayed on the street like a beggar for even an hour, and for the first time in my life I had to start from zero: living in the mountains, looking for wood, learning how to make a fire, how to boil water, how to cook! [laughs]

BDG: Did your retreat also change your approach to teaching the Dharma?

YMR: Oh yes. Now I want to teach in a more experiential way—with what I call “head, heart, and habit.” We have to understand the Dharma not only with our head and heart, we have to bring it to the practical level—something we can deal with in everyday life. So that’s now my focus.

BDG. It can be very difficult for lay Buddhists and householders managing the responsibilities and obligations of their families and careers to maintain a regular meditation practice. Do you consider retreats and solitude to be an essential aspect of the Buddhist practice?

YMR: Normally what I say is, for me it was wonderful, but not everyone has to go through this. In our lives there are a lot of challenges and one thing I learned from my retreat was how to face challenges. Nowadays, when you reach 18 years old you have to leave your parents’ home and learn to survive every day by yourself. And life has a lot of problems. If you can meditate, it’s not necessary to always go into the mountains—you can meditate anywhere, at any time, under any circumstances.

BDG: There has been a rapid growth in the promotion of meditation and mindfulness as a path to happiness in recent years, notably in the West. Do you find that this focus on happiness has been over-emphasized compared with undertaking such practices as a means to understand the nature of existence, as described by the Four Noble Truths?

YMR: I think sometimes there are misunderstandings. People sometimes think that Buddhist meditation is about becoming happier, like going to a spa! I think that’s becoming quite a common misunderstanding. Meditation is really about trying to find out who you are—the nature of yourself, the nature of reality, and deeper, deeper. . . . There are many layers to meditation and what we call liberation. The development of meditation leads to liberation; freeing yourself—what in Buddhism we refer to as nirvana, enlightenment.

BDG: Do you think that’s achievable for people today living hectic urban lives?

YMR: Full enlightenment is quite difficult. But the first step toward enlightenment, that’s possible! In fact, Buddhist meditation is the essence of Buddhism. In Tibet, we have grandfathers and grandmothers who know nothing about Buddhist philosophy, they simply meditate. They can achieve that first level of realization and they are full of happiness! They practice with a prayer wheel and understand impermanence: if I die tomorrow, okay; if I live long, wonderful!

The first level of meditation, anyone can practice, but the deeper levels of meditation are the heart of the Buddhist practice. So that, I think, has to come step by step. Now I’m introducing the Joy of Living as a path of liberation.** The Joy of Living program has a secular basis: basic meditation. For those who are really interested in a deeper level of meditation, then you have to go into the Buddhist path of liberation.

BDG: Do you consider the broader acceptance of Himalayan Buddhist traditions around the world to be a positive trend? Or do you see a danger that teachings, traditions, and rituals that have been preserved for centuries could become diluted and misunderstood?

YMR: Now we are at a turning point. Some rituals may disappear, I think, after some time, but not the essence. The Buddha said the teachings depend on people’s mentality, personality, and culture. Now, in accordance with that, the examples and the methods of teaching need to change to match with the modern mentalities and capacities. Now, in the 21st century, we have to be ready to let go of some cultural influences of the past. But the essence of the Dharma, there’s no need to change.

BDG: Isn’t the increasingly commercial and materialistic face of 21st century society becoming incompatible with the practice of the Dharma?

YMR: That’s really a very important point now. Many people now are really searching, they have a spiritual hunger. . . . That’s a deep question, right? It’s quite possible that traditional Buddhism may eventually disappear, but experiential Buddhism may well become more developed.

BDG: Religion and spirituality have long been vulnerable to teachers who may not have their students’ best interests at heart, or who are willing to exploit naiveté or inexperience for their own personal gain. Do you have any advice for lay Buddhists—especially those who may be approaching the Dharma for the first time—to help them discern authenticity in the teachers or communities they encounter?

YMR: It’s important to check any teacher—really important. There are four important qualifications for teaching: first, they must have an authentic lineage; second, a history of study and practice within that authentic lineage; third, the teacher needs to demonstrate ethical conduct, especially compassion and care for the students; and fourth, humbleness is very important: if the teacher says “I am enlightened,” “I have this super power,” “I am special,” that means there’s something wrong; that’s not the right teacher for you. So these four points are really important if you’re looking for a genuine teacher.

BDG: Buddhism is sometimes referred to as a “scientific” religion, and many people have argued that science can help to corroborate the Buddhist teachings. Do you see any potential pitfalls from approaching Buddhism from an empirical/materialist perspective?

YMR: Buddhism is what we call a science for exploring the nature of reality and for exploring how the mind works—who you are, how you perceive reality—which is very similar to modern science. So I use a lot of examples from science when I teach. But it doesn’t matter if we refer to modern science or not, the practice of Buddhism continues. It’s not dependent on science. Science can be used as an example to understand or look at reality from a different perspective, but in Buddhism we go beyond science and beyond the intellect.

BDG: During your recent visit to Hong Kong you spoke on the subject of death and dying. What are some ways in which lay Buddhists can approach death—both for themselves or when caring for loved ones?

YMR: It’s very important to prepare oneself for death. No matter what, we all have to face this. To prepare, you must try to understand what death really is and what kind of experiences you might face. In Buddhism we have a stage-by-stage explanation of the process of dying. During the first month of my wandering retreat I almost died and I had all these experiences, step by step, just as the teachings describe. In the end I saw that awareness never dies, and so I remained in awareness.

So practice awareness from now, practice letting go, practice developing meaning, motivation. Death is such a great opportunity for us: for Buddhists it is the best moment to attain liberation or enlightenment at the moment of dying because the conceptual mind dissolves. So now what do you have? Only pure awareness, which cannot be destroyed. Therefore, try to develop this motivation: I’ll die for others! Use dying as a mind practice; learn until the last breath, grow until the last breath. Practice, practice until the last breath—then you will have a great discovery, I think!

* Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche Returns from Four-year Wilderness Retreat (Buddhistdoor Global)

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche Releases Video Offering Insights Following His Retreat (Buddhistdoor Global)

** What is the Joy of Living? (Tergar)

See more