Editor’s note: This feature was first published in the now-retired Bodhi Journal, Issue 4, June 2007.

A: I’ve a lot of worries and stress. I try to meditate in order to relax, but it is no Use.

T: In this fast moving world, meditation is regarded as an instant remedy for life ills. If you look upon meditation as merely a tranquilizer, you’re underestimating its true value. Yes, relaxation does occur through meditation, but that is only one of its many results. Meditation in Buddhism is neither an instant cure nor just a stress-relieving measure.

Meditation in Buddhism means cultivation of the mind in order to achieve

insight wisdom or paññ?, ultimately leading to liberation or nibb?na.

D: Nibb?na aside, I want to meditate, but I can not find the time.

T: When you speak of meditation, you may think of the type of meditation that is popular these days, the sitting form of meditation. But that form is merely an aid, a support to develop a mental discipline of mindfulness and equanimity. The form should not be mistaken for the path.

The popular notion is that you need to set aside a special time or place to meditate. In actuality, if meditation is to help you acquire peace of mind as you function in your life, then it must be a dynamic activity, part and parcel of your daily experience. Meditation is here and now, moment to moment, amid the ups and downs of life, amid conflicts, disappointments and heartaches – amid success and stress. If you want to understand and resolve anger, desires, attachments and all the myriad emotions and conflicts, need you go somewhere else to find a solution? If your house is on fires, you would not go somewhere else to put out the fires, would you?

If you really want to understand your mind, you must watch it while it is angry, while it desires, while it is in conflict. You must pay attention to the mind as the one-thousand-and–one thoughts and emotions rise and fall. The moment you pay attention to your emotions, you will find that they lose their strength and eventually die out. However, when you are inattentive, you find that these emotions go on and on. Only after the anger has subsided are you aware that you have been angry. By then, either you’ve made some unwanted mistakes or you’ve ended up emotionally drained.

R: How do you handle these emotions? I know that when I’m angry, I want to shout and throw things. Should I control these emotions or express them?

T: The natural inclination is to try to control the emotions. But when they are kept under a lid, they try to escape. They either rush out with a bang or they leak out as sickness or neuroses.

R: What should I do? Do I let my emotions go wild?

Certainly not. That is exactly what we don’t want to do. That is another extreme – to release your emotions impulsively. The important thing is neither control nor non-control (Editor’s note: equanimously). In either situation, you are working up your desire to control. Neither situation is tenable. So long as this desire occupies your mind, your mind is not free to see anger as it is. Hence, another paradox arises: the more you want to be free of the anger, the more you are not free of it.

To understand the mind, you’ve to watch and pay attention with an uncluttered silent mind. When your mind is chattering away, all the time asking questions, then it lacks the capacity to look. It is too easy asking questions, answering, and asking.

Try to experience watching yourself in silence. That silence is the silence of the mind free from discriminations, free from likes and likes, free from clinging.

Thoughts and emotions by themselves are just momentary and possess no life of their own. By clinging to them, you prolong their stay.

Only when your mind is free from clinging and rejecting, can it see anger as anger, desire as desire as soon as you ‘see’, your mental process is fully occupied with ‘seeing’, and in that split second, anger dies a natural death. This ‘seeing’ or insight is called paññ?. It arises as a spontaneous awareness that can neither be practiced nor trained. This awareness brings insight to life, new clarity and new spontaneity in action.

So, you see, meditation needs not be separate from life and its daily ups and downs. If you’re to experience peace in this everyday world, you need to watch, understand and deal with your anger, desire and ignorance as they occur. Only when you cease to be involved with your emotions can the peaceful nature of your mind emerge. This peace nature enables you to live every moment of your life completely. With this newfound understanding and awareness, you can live as a complete individual and greater sensitivity. You will come to view life with fresh perceptions. Strangely enough, what you saw as problems before are problems no more.

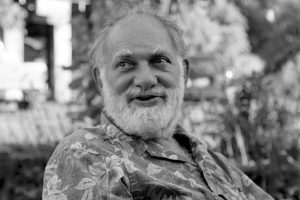

Editor’s Note:

Dr. Thynn Thynn, who received her earlier training in Buddhist meditation on Mindfulness from Saya U Eindasara of Rangoon and Sayadaw U Awthada of Henzada, is currently the Chief Yogi Instructor of the Sae Taw Win II Dhamma Centre, Sebastopol, California, United States. She had taught previously in Bangkok. Currently, she is instructing Buddhist meditation in United States and Canada. She specializes in the Dry Insight vehicle (Vipassan?y?nika) to lead the practitioners or yogis to actualize the absolute mental appeasement which she designates it as the ‘Silence of the Mind’. This ‘Silence of the Mind’ is actually the Nibb?nic experience which a practitioner can experience in the midst of all ups and downs of daily mundane transactions of life. Her pedagogy is akin to the Buddhist Chan or Zen or Krishnamurti teaching. Her teaching of Right mindfulness and Clear Awareness undoubtedly concurs with the Gotama Buddha’s exposition of Four Foundations of Mindfulness (Satipa??h?na). Readers, who are interested in the social function of Buddhist meditation, should not hesitate to contact her through:

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: www.saetawwin2.org/~stw2