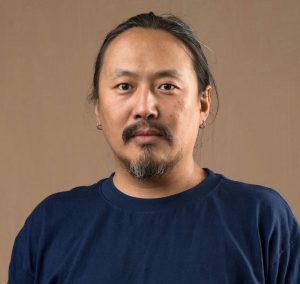

The Korean Seon (Zen) master Venerable Pomnyun Sunim (법륜스님) wears many hats: Buddhist monk, teacher, author, environmentalist, and social activist, to name a few. As a widely respected Dharma teacher and a tireless socially engaged activist in his native South Korea, Ven. Pomnyun Sunim has founded numerous Dharma-based organizations, initiatives, and projects that are active across the world. Among them, Jungto Society, a volunteer-based community founded on the Buddhist teachings and expressing equality, simple living, and sustainability, is dedicated to addressing modern social issues that lead to suffering, including environmental degradation, poverty, and conflict.

This column, shared by Jungto Society, presents a series of highlights from Ven. Pomnyun Sunim’s writings, teachings, public talks, and regular live-streamed Dharma Q+A sessions, which are accessible across the globe.

The following teachings were given in San Jose on 13 September 2023. This article is the 13th in a special series taken from Ven. Pomnyun Sunim’s Dharma tour of Europe and North America—his first overseas tour since the pandemic. Titled “Casual Conversation with Ven. Pomnyun Sunim: Come Talk about Life, Wisdom, and Happiness” the Dharma tour ran from 1–22 September 2023, taking in 21 cities: six in Europe and 15 in North America.*

Understanding socially engaged Buddhism

In the afternoon before the Dharma talk in San Jose, Venerable Pomnyun Sunim had a meeting a book publisher, who had been proposing to introduce Sunim’s Dharma teachings to Americans for several years. On hearing about Sunim’s visit, the chief executive of the publishing company came to visit in person, noting that he had been following Sunim’s teachings on YouTube for some time. Toward the end of their conversation, Sunim discussed the book he hoped to publish for Americans.

Ven. Pomnyun Sunim: The book I’d like to publish in the United States is titled The Life of the Buddha. Until now, the story of the life of the Buddha has been treated as too religious and mystical. However, by writing a new book introducing the Buddha’s life, I want to help people understand how he lived as a person.

At the time when Buddha lived, 90 per cent of the people were slaves. As they grew old and sick, they became useless and were therefore abandoned—even when they were sick, they received no protection. When people died, they were usually cremated, but the slaves were not given this treatment. Their bodies were discarded in the forest like trash. It was through encounters with abandoned elderly people, the sick, and corpses outside the palace where the Buddha lived that he first began to question things.

If we talk about this in the traditional Buddhist way, it would be said that the Buddha saw that all people grow old, get sick, and die. However, if we interpret this from the perspective of the social structure of the time, we can understand that the Buddha experienced the suffering and inequality endured by the lower classes in society. Faced with this harsh reality, the Buddha fell into the question of “What should I do?”

“Do I seek a winner’s life to avoid becoming like them? Or do I dedicate myself to creating a world without such suffering?”

The Buddha’s father, King Suddhodana, entrusted a region of his kingdom to the Buddha to rule in order to distract his son from his worries, but the Buddha-to-be liberated all the slaves there and released all the cattle. He soon realized that this method was unsustainable for the world at large. He realized that he couldn’t resolve this dilemma through the ways of this world, and eventually chose the path of renunciation.

If you follow the life of Buddha like this, you cannot help but encounter the social issues of the time. The Buddha faced great resistance from society because of his views on class and gender discrimination. At that time, women were not regarded as independent individuals but as mere accessories or possessions of men. Thus a woman always had a master, whether it was her father, her husband, or her son. Consequently, permitting a woman to renounce and become a bhikshuni (a female monastic) was an extremely challenging endeavor. It meant that she was no longer someone’s accessory but had her own identity.

Because it was a system that had never existed before, it was not easy for even the Buddha to allow it. In fact, it took nearly 20 years after the Buddha’s enlightenment for women to be permitted to renounce. However, the female monastic order disappeared again some 500 years after the death of the Buddha. So now, in Theravada Buddhism, the renunciation of women is not acknowledged. This illustrates how severe gender discrimination was in society at the time.

There was also a lot of resistance when slaves wanted to join the Buddha’s sangha. From the perspective of slave owners, allowing a slave to renounce meant losing their property, so they often tried to recapture them. For a slave to become a monk meant breaking free from the bondage of his owner and becoming the master of his own life. This was tantamount to a complete denial of the social system.

When you focus on Buddhist ideas or doctrine, you will deal with philosophical issues alone. Only by studying the life of the Buddha can we talk about real-life social problems. This is because the Buddha was a person who lived in a concrete social reality.

Living life lightly

When Sunim took to the stage for that evening’s Dharma Q+A, he was welcomed with loud applause. He began the conversation by sharing the news from Libya, where a devastating flood had left many casualties.

Ven. Pomnyun Sunim: Today, I received the heartbreaking news of a devastating flood in Libya, where a dam burst has caused many deaths and with many still missing. The climate crisis is bringing about more extreme heatwaves, heavy rainfall, wildfires, and so on. It seems that our pursuit of convenience—believing that producing and consuming a lot means living well—is ultimately leading to this environmental crisis. To live sustainable lives, we must reduce our consumption, even if it is a little inconvenient. I believe that we can prevent this crisis by not trying to gain joy only by satisfying our desires but by pursuing a life of satisfaction through appropriate moderation.

Q: My question is about how to live life “lightly.” Sunim advises people to live life lightly, like grass in the field. But you seem to live a heavier life than others. Is it just my misconception? I’d like you to clarify what it means live lightly.

Ven. Pomnyun Sunim: If a young boy were to carry a 30-kilogram weight, it would be a heavy object. If the boy continued carrying that weight, it may strain his body and cause him to become ill from overwork. Conversely, if a healthy adult were to carry a 30-kilogram weight, it wouldn’t pose a significant difficulty. If you put 30 kilograms of stuff on the back of an elephant, it won’t mind. The perception of whether something is heavy or light depends on one’s ability and physical strength. You cannot label something as heavy or light based solely on its weight.

The Buddha’s mind is like a mirror. For example, let’s say that this tray is a mirror. When a microphone appears in front of this mirror, it reflects the microphone. When a cup appears, it reflects the cup. When a flower appears, it reflects the flower. So how many different images can this mirror create?

Q: It can create an infinite number of images.

Ven. Pomnyun Sunim: However, we can also say that this mirror does not create a single image. It effortlessly reflects a thousand or ten thousand images. When something comes before the mirror, it merely reflects, and when it passes, it disappears.

When you are attached to something, you live your life as if you are carrying a heavy burden. When you become greedy, wanting things to happen exactly as you desire, or when you insist on doing things your way, or pretend to know when you don’t, that’s when you exert effort. Letting go of such things makes your life easy.

Of course, since we have a body, there are times when we feel physically overloaded. So if you don’t have enough sleep, just sleep. If your body is tired, you can rest. If you get sick, just take medicine. If you do not get better after taking medicine, you can go to the hospital. Eventually, when it’s time to die, just die.

There’s no big problem: this is what it means to live lightly. It means doing your best but not being attached to the results. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do anything; it means you should do something and not be concerned about the results.

There is nothing in this world that you must do. You don’t have to do anything—or you can do it if you want. However, once you make a choice, you must take responsibility for your choice. Just as there are causes, there are effects, and we should accept that responsibility.

Q: If I was born as a blind person, for example, then am I supposed to accept the fact that I was born into unfortunate circumstances and live the best I can? How would you advise that person?

Ven. Pomnyun Sunim: We must have the perspective that we can lead a happy life even if we are born blind. It’s just a little uncomfortable because you can’t see. And society must come up with mechanisms to compensate for this inconvenience. However, being born blind is not in itself unequal. Is it unequal to be born with white or dark skin? Is being tall or short unequal? It’s not like that. Regardless of how they were born, everyone can live a happy life.

The Four Pillars of Destiny

Q: Do the Four Pillars of Destiny (Kr: 사주팔자; saju palja [a system of astrology and divination found in East Asia]) have a scientific basis?

Ven. Pomnyun Sunim: In the time of Buddha 2,600 years ago, it was very difficult to understand human inequality. At that time, Indian people understood that inequality was caused by karma from previous lives. In China or Korea, people understood that inequalities stemmed from differences in birth date and time. Elsewhere, they understood it as the will of God. So you can consider the Four Pillars of Destiny as one way of understanding the world under the conditions of that time.

Science is how we understand the world today. Scientific method is the easiest way for us to understand the world. However, in the future, when eras change, things may happen that are difficult to understand even from a scientific standpoint.

The question of whether the Four Pillars of Destiny is scientific is based on a sense of certainty that what is scientific is unconditionally the truth, and what is not scientific is not the truth. However, our happiness today cannot be fully revealed by science. Enlightenment has a nature that transcends even rationality. Rationality is also an absolute concept. You must give up even that in order to reach true freedom.

If, in the past, the way we understood life meant that we understand just 10 per cent of the world. The way that science understands the world today is to understand 70 per cent. Just as in the medieval era, the saying, “This is not the word of God,” was synonymous with something not being true, today the term “nonscientific” to us has become synonymous with being false. However, we shouldn’t assume that we can understand 100 per cent of the world through science. Because in the future, new ways to understand the world more fully may be discovered. As such, rather than saying that people back then were foolish and that we are smarter now, we must understand that the standards of value for viewing things has changed between then and now. Our framework for understanding the world has changed.

The reason why rapid changes in today’s society confuse you is not because the world is confusing, but because the changes in the world cannot be understood within the limited framework of perception that we hold. The world seems confusing because we don’t understand. To properly understand the world, you need to change your frame of perception—but there is no problem with the world. The world just changes.

If possible, I hope you can change your karma a little more so that you can see the world as it is. By doing that, we can live in any world without suffering. This should not be misunderstood to mean that the world is always good. When necessary, we must change the world. You may need to make sacrifices along the way. However, this also means that even sacrifices can be made without suffering. It means that if it’s the path we’ve chosen, we should willingly walk it, no matter the difficulties there may be.

Q: Thank you.

See more

Pomnyun

Jungto Society

JTS Korea

JTS America

International Network of Engaged Buddhists

Related features from BDG

Prostrating as a Part of Buddhist Practice

Suffering and the Significance of Insignificance

Treasure the Present and Value Your Own Life

Free Will and Freedom from Suffering

Do Not Sacrifice Later for Now

Begin Life Now

Becoming the Master of Your Own Life

You Are Alive Today

Everyone Has the Right to be Happy

Personal Action to Mitigate the Climate Crisis

Awareness, the Beginning of Change

How to Live Life More Freely

Related videos from BDG

Dharma Q+A with Ven. Pomnyun Sunim

Wisdom Notes from Ven. Pomnyun Sunim