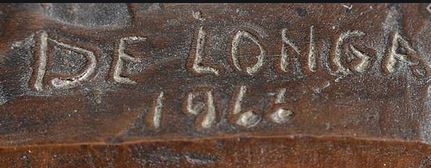

In college, I had a very influential professor, Leonard DeLonga. He led the sculpture department at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, where I attended classes while a student at Smith College. According to his widow Sandy, herself a very fine ceramic artist, Leonard was hired to take the small existing sculpture department and turn it into a serious studio. The school gave him unlimited freedom and resources to create the ideal full-scale sculpture program, which blossomed under his care.

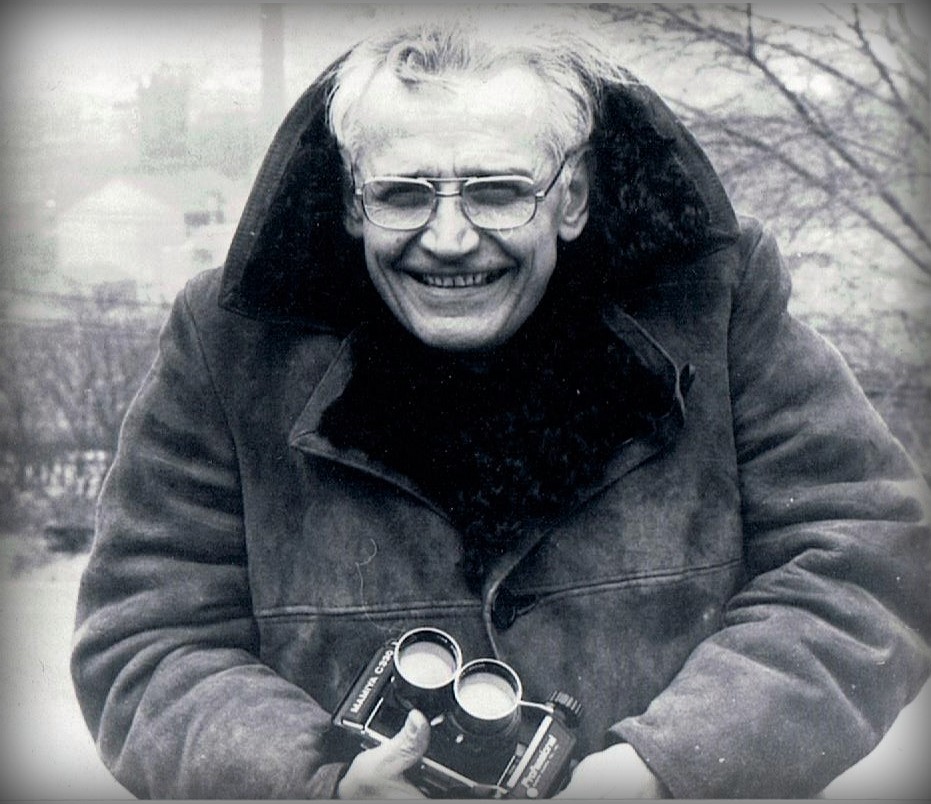

Although I have met several remarkable and charismatic teacher-leaders over the years, none have come close to the special qualities of DeLonga, as we affectionately called him. He died prematurely of a brain tumor in 1991, but his legacy lives on in the hearts of many. I often refer to him in my mind as The First Bodhisattva (the first whom I met): a compassionate figure whose time and energy were spent helping others. I took refuge as a Buddhist nine years after his passing, so it was in retrospect that I saw DeLonga in this light—as someone who worked tirelessly and with great joy for the benefit of others. We all knew that he was extraordinary, but it wasn’t until later that I had this language to describe his way of being with people. Another former student described him as the “legendary sculpture professor from Mount Holyoke College who became very much like a father to me and to many others.” He was a gentle giant. He was large in stature, as were his bronze creations. DeLonga and his art were powerful and monumental, perhaps intimidating at first glance. But he had a heart and spirit that were generous, gentle, kind, and infectious. He guided me and allowed me great freedom while in his sculpture class, as he simultaneously counseled me about life.*

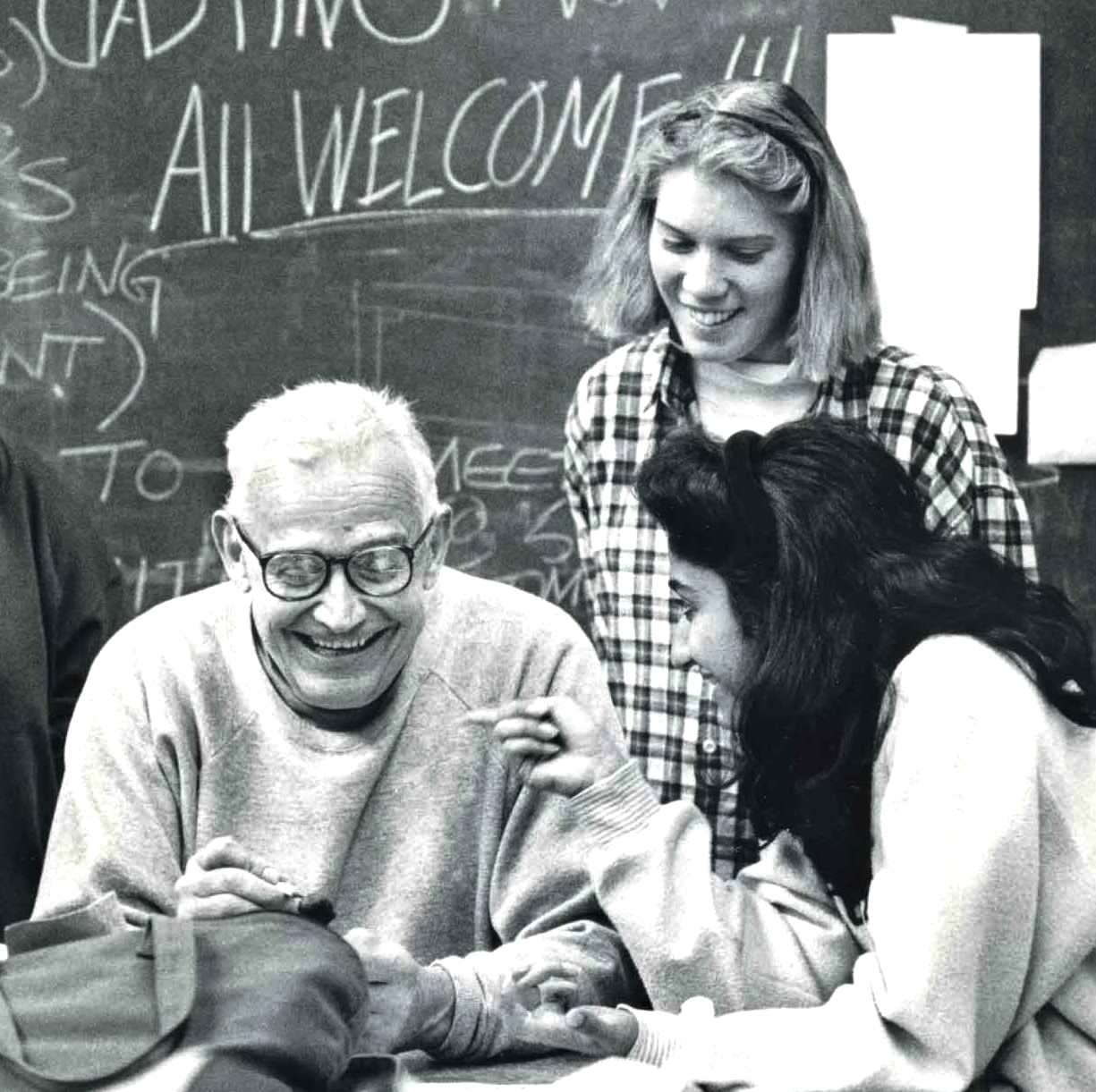

In the sculpture studios of this small Ivy League liberal arts college, DeLonga had an intimate laboratory in which to develop and hone his potent educational and social methods over a period of 25 years. Despite course section limits of 20, DeLonga refused to turn away any student (whether an art student or another major) wishing to attend his sculpture classes. He often took in up to 80 or 100 students per section! His classroom, rather than feeling crowded, felt full of creativity, experimentation, and a sense of excitement and collaborative learning. He was much beloved by his many students. DeLonga had boundless room in his heart, as well as in the physical space, for all students who gravitated toward making art, and an aura of egolessness. He accommodated everyone by having large initial class gatherings to share ideas together, and then scheduling studio time with equipment to accommodate everyone on staggered schedules.

Artist-scientist viewpoint

Lately, I have been reading about the hermeneutical framework of leadership. This paradigm seems very closely aligned with DeLonga’s approach to both teaching and to leadership. The essence of his approach to being a creative artist and a teacher was to examine the meaning inherent in the world around us. His inherent artist-scientist view of life and art-making was a deeply inquisitive, curious, imaginative approach. DeLonga was driven by how meaning becomes imbued by our own interpretations and interactions in both the natural and created worlds.

I remember a vivid example. I was stuck with “artist’s block” or blank page syndrome during his course. Drawing was usually a prelude to sculpting. When he asked me if I had any ideas or impulses, I said no; no sketches in my art journal. I noted that my philosophy class was hard for me. I was struggling there with annoyance and boredom, and spent my time distracted and irritable, doodling in the margins of my philosophy notebook! DeLonga asked to see those margin doodles, and together we discovered, with his guidance, that my subconscious mind had plenty of material for a sculpture series. He helped me to see the meaning I was making in the larger context of how I spent my time and where my mind wandered. I used these doodles (of patterns of triangles) to create a series of abstract sculptures in bronze sheeting, which had unique meaning to me about one’s relationship within the spatial world, as well as a beauty all their own due to the movement and relationship of shapes and empty space.

Teacher as catalyst

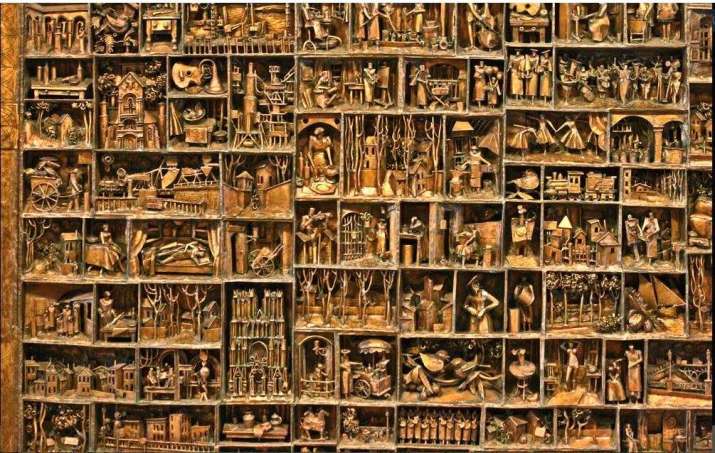

DeLonga spent the majority of his time gently eliciting from his students their inner personal connections to life and the world, that they might turn their experiences into physical manifestations in bronze, steel, marble, and mixed media. He also did this by example, as a prolific working sculptor and painter. He taught us about great art masters of the past, always connected to our own thoughts, dreams, wishes, and life experiences. DeLonga showed an affinity with the hermeneutical approach to understanding and meaning-making. He beautifully embodied what I think of as an alchemical process, characterized by educator Jack Culbertson: “Inquiry itself has been described as a kind of imaginary conversation or dialogue to produce new meanings. There is no presumption of neutrality on the part of the researcher toward the object studied.”* The example of DeLonga pointing to my margin doodles as imbued with potential meaning or personal relevance demonstrates his deep belief in “the role of the Inquirer to mediate between the familiar and strange to achieve new meaning” within a student’s own cultural and personal context.**

Feminism as humanism

DeLonga’sway of teachingreliedstrongly on key points of feminism in our society. He was a kind, mischievous, lighthearted man, yet also took his job at a prestigious women’s college very seriously. I was one of his students chosen to be a teaching assistant (TA) in the sculpture studio. Although male students from the surrounding four colleges could attend courses at Mount Holyoke (through the Five College Consortium), those chosen to be TAs had to be female. This remains one of the most positive, empowering experiences of my life. The young men worked alongside us on bronze-casting days, or in helping new students learn to weld, or to carve stone. Although they often performed the same duties as a TA, they were not paid (as work-study) or recognized as such.

I remember vividly the sense of camaraderie and non-competition that was present among us. My male student colleagues showed no signs of bitterness that they had not been hired as TAs, rather they supported us female TAs with a sense of collaboration and shared work that I daresay I have not felt in an educational setting since. I believe this was due in large part to the atmosphere of equality that DeLonga upheld and brought to us all. He treated each and every student with genuine, deep loving-kindness and interest (even those challenging few that are in any group). He treated men and women as equals, while uplifting women to balance out societal inequities in a manner that did not harm or alienate anyone. This surely was a life lesson not to be forgotten by any of us, male or female.

DeLonga was extremely encouraging of all his students and made sure to ask about and remember each one’s future plans, whether in art, politics, the sciences, or raising a family. He maintained connections with students for years, even decades after they graduated, and invested himself in their successes like his own children. When female students shared their experiences of misogyny or gender bias, he was a ready listener and advocate, a feminist by nature. There were very lively socio-political conversations, as many students were international, and shared their perspectives beyond US cultural norms. DeLonga was ready to challenge his students (especially the fiery ones!) about their viewpoints, but he always did so with clear respect and genuine care for their well-being and growth as full human beings.

Photo by Shannon Collins Pan

Special breakfast gatherings

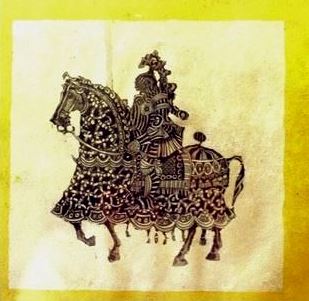

DeLonga was motivated to discover within each of us what we truly had to share, and to cultivate our own voices through the visual arts. Many of his students were from Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan, as well as African and South American nations. DeLonga facilitated the empowerment of others, in finding their voices and visual means of expression, often to showcase the oppression and suffering of people from their cultural or geographic backgrounds. Each bronze-casting date was marked by an early morning breakfast gathering, at which we were all invited to ask a question, any question at all that lived in our hearts. It could be about art, casting, life, love, plans, or an existential/philosophical dilemma. DeLonga delighted in knowing what mattered to us, and he responded equally from his own heart—often with further clarifying questions, always with a sense of deep caring and curiosity.

The laboratory of the art studio was a vital gathering place, where around an egalitarian table we would all sit and discuss our thoughts and feelings in relation to current events, in the world and in our lives. DeLonga carried a brown canvas bag full of unshelled peanuts (and sometimes Hershey’s kisses), which he would dump out on the table for all to partake. Our teacher fostered an especially sensitive atmosphere of truly listening to and learning from one another. He took obvious pleasure in helping each of us relate to the art materials we felt an affinity for, and to create art to express the range of experiences in our lives. I particularly remember certain conversations between DeLonga and students from Pakistan, who were very passionate about the gender politics and power struggles in their country. One Poly-Sci/Art double major loved to argue with him about many topics, and he delighted in the exercise, as it clearly helped her to hone her skills of debate and research-backed oration.

In creating art from the raw materials of metal and stone, we relied on theories and practices based on physics and the scientific method of problem-solving—and our research analysis in welding and bronze casting—to work out the physical problems of how to render our imagined and drawn ideas into literal form. Casting in bronze is an alchemical experience, turning molten metal into solid form. We used quantitative data and tested practices to repeat applications with materials and tools to achieve our desired results. We use various standards and repeated behaviors, both for safety and quality control. We based our work on what we knew to be true in the present moment and from reliable methods from our history of practice. DeLonga modeled this approach through his reliance on the physically tested aspects of art-making, and his many years of personal applied research into what works and what doesn’t to achieved desired results in metallurgy. Science and art truly blended together in our practice of casting, welding, or carving into form what was born in our imaginations, with DeLonga as our cheering squad and co-investigator. All this occurred in the laboratory of curiosity, bound by love.

Teaching, a path of love

It is fair to say that for the past 28 years I have striven to embody the values and methods of my mentor Leonard DeLonga. My own beliefs closely align with making meaning for ourselves. In order to interpret and understand the world, we have to delve deep into our experiences to create continuity and meaning. I also strive to be ever-inclusive of feminism and social justice in every kind of work I undertake. When we look critically at our society, we see not only the positives in how we came to be where we are now, but the challenges that face us in becoming an even more just and loving society.

Photo by Shannon Collins Pan

The methods, worldview, and approach of my teacher DeLonga could be essentialized into one word: love. He loved teaching, art-making, meaning-creation, and encouraging each student he met, with a rare quality of boundless interest and acceptance for each one’s unique expression. He loved his wife Sandy and their two children with a reverence, humor, and joy rarely seen. If I lead, mentor, or teach with even a little of his patience and regard for others and for the undertaking, I will feel content. I hope to embody his way of servant-leadership, so that students and colleagues benefit from my way of being in the world, as well as more directly from my work and development.

Bringing conscious awareness to teaching

There is deep value in being aware of one’s own motivations and methods, including our unconscious biases and contexts. If we can look at our own places of power and privilege, we may see how they can subconsciously influence the ways in which we work with students. We could have a common commitment—as teachers, students, and administrators—to become aware of our reliance on assumptions of both the content and structure of our educational systems. Leonard DeLonga’s teaching, learning, and leadership styles were unique in academia. He remains a vivid role model, mentor, and inspiration for many of us, even decades after leaving his physical form. He was the first person I met with clear bodhisattva qualities. He spent his life inspiring and caring for others in exchange for a sense of deep contentment and joy.

Image courtesy of the author

** Culbertson, J. “Three Epistemologies and the Study of Educational Administration,” in University Council for Educational Administration, XXII, 1, Winter 1981, p.151.

Sarah C. Beasley (Sera Kunzang Lhamo), author of Kindness for all Creatures: Buddhist Advice for Compassionate Animal Care (Shambhala 2019), has been a Nyingma practitioner since 2000, a certified educator, and an experienced writer and artist. She has a BA in Studio Art and an MA Candidate in Educational Leadership. Sarah spent close to seven years in traditional retreat under the guidance of Lama Tharchin Rinpoche and Thinley Norbu Rinpoche. With a lifelong passion for wilderness, she has summited Mt. Kenya and Mt. Baker, among other peaks. Her book and other works can be seen at www.sarahcbeasley.com.