Since the 14th century, merchants have plied the waters between the ports of Singapore and Calcutta (now Kolkata) in India. In 1818, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles sailed from Calcutta to Singapore to claim it as a British colony, and between 1823 and 1867, British Singapore was governed by the East India Company out of Calcutta. Even after Singapore’s independence in 1965, the two cities remain closely linked in many ways. In celebration of 50 years of diplomatic relations between India and Singapore and to commemorate the latter’s 50th year of independence, a first-ever collaboration between Indian and Singaporean museums—the exhibition Treasures from Asia’s Oldest Museum: Buddhist Art from the Indian Museum, Kolkata—is currently taking place at Singapore’s Asian Civilisations Museum. On view until 16 August, the exhibition is a showcase of Buddhist-inspired works spanning the 2nd century BCE to the 17th century CE.

The largest and oldest museum in Asia, Kolkata’s Indian Museum was founded by the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1814 and contains extensive holdings of Buddhist art. The Asian Civilisations Museum, located at historic Empress Place at the mouth of the Singapore River, provides an apt location for the exhibition as it was here in the early 19th century that the early Indian immigrants first landed. An obelisk still stands outside the museum commemorating Indian viceroy Lord Dalhousie’s visit from Kolkata in 1850.

To walk through the gallery of dramatic sculptures and reliefs is to take a journey back in time and to witness the Buddha’s past lives as told in the Jataka stories, his life as Prince Siddhartha, his enlightenment under the Bodhi tree, his first sermon at the Deer Park in Sarnath, and his mahaparinirvana. Through this visual biography, one sees the evolution of Buddhism and its concepts through the centuries, from Theravada to Mahayana to Vajrayana, and from the early aniconic imagery to the various anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha and the pantheon of bodhisattvas and deities inspired by the rich Indian traditions.

Among the oldest of the exhibits are large, round medallions from the railing pillars that surrounded the Bharhut stupa. Unearthed by British archaeologist Alexander Cunningham in the Satna district of Madhya Pradesh in central India, the Bharhut stupa is believed to have been built by the emperor Ashoka during the Mauryan era (322–180 BCE). In this aniconic phase, the Buddha is never seen but is present through symbols such as the Dharmachakra or “Dharma wheel,” which represents the Buddha’s universal teachings; the Bodhi tree, representing his enlightenment; and the Buddha footprints, the empty throne, the lions, and the lotus.

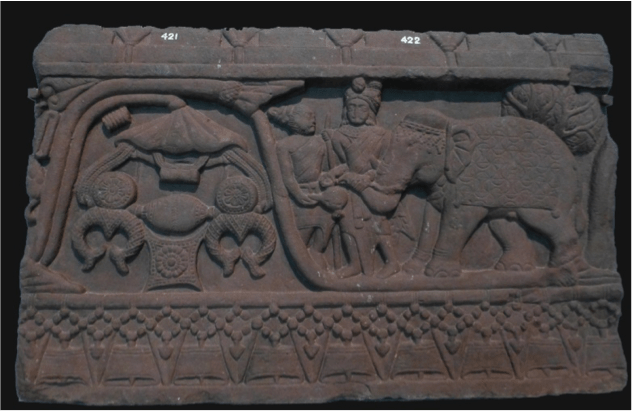

Jataka tales, or stories of the Buddha’s previous lives, are popular themes for Buddhist art in all forms. One of the four reliefs from Bharhut depicts the story of Prince Vessantara, who is renowned for his extraordinary acts of generosity.

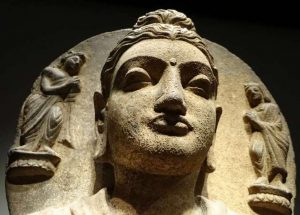

During the Kushan period (1st–3rd century), anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha began to appear in northern India. By the time of Kanishka the Great (r. 127–51), the Kushan empire had expanded such that it was governed by two capitals, Mathura in northern India and Purushapura (now Peshawar) near the Khyber Pass, correspondingly giving rise to two great artistic centers each with a distinctive style—Mathura and Gandhara.

The Mathura style developed from indigenous Indian traditions derived from the Mauryan and Shunga (c. 185–73 BCE) dynasties. Carved from mottled red sandstone, Mathura Buddha images are voluptuous and round-bodied, and clad in thin muslin garments that cover the left shoulder. Often, the palms and soles feature Dharma wheels and the Buddha is seated on a lotus.

In contrast, Gandharan figures display strong Greek and Roman influence, due no doubt to the legacy of Alexander the Great’s eastward campaign in the 4th century BCE and the concept of the “man-god” inspired by Greek mythology. Created from dark gray phyllite, schist, stucco, or terracotta, Gandharan images have a realistic idealism that combines human features, proportions, and emotions with a sense of perfection and serenity approaching the divine. The figures wear toga-like garments, and have wavy hair and straight, Roman noses.

The difference between the two styles is well illustrated by two sculptures from the same period and of the same subject—that of the deity Hariti and her consort, Panchika. The Mathura representation features squat, humorous characters, and Panchika is depicted with a pot belly. In the Gandharan version, the figures are slender and elegant, with flowing drapery like the ancient Greek gods. The standing figure of Panchika has a sculptured, muscular body and wears only a loin cloth.

The Gupta period (4th–mid-6th century) was the Golden Age of India, with great progress being made in every field, from science to engineering, literature, religion, philosophy, and art. Mahayana Buddhism flourished alongside the dominant Hindu religion. Buddhist art also reached its zenith, and stone was transformed into images of superb beauty through perfect precision and masterliness. Gupta art became the model for the coming ages, and had tremendous influence throughout Asia.

Artifacts from the Pala period (8th–12th century) form a substantial part of the exhibition. The Palas were great patrons of both Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, and bodhisattvas such as Avalokiteshvara and Manjushri were depicted together with the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni. Although it is not clear if the Pala kings were themselves Buddhist, Buddhism and its arts thrived, with Buddhist pilgrims, monks, and students from all over Asia flocking to the holy sites connected with Shakyamuni’s life and to the numerous monasteries and Buddhist universities in India. As a result, the Pala style had a strong influence on the art of Burma, Nepal, Tibet, Shrivijaya, and Java.

By this time, the Buddha’s life had been codified into a series of “Eight Great Events”: his birth, his defeat over Mara and subsequent enlightenment, his first sermon, the miracles he performed at Shravasti, the descent from Trayastrimsha Heaven, his taming of a wild elephant, the monkey’s gift of honey, and his mahaparinirvana.

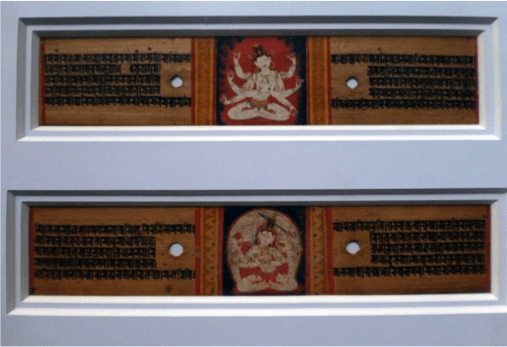

Esoteric Buddhism had already begun to flourish by the 5th century, and with the many rituals of Vajrayana, both Buddhist images and Buddhism itself became more complex. Statues and paintings with multiple faces and arms depicting the array of Buddhas, bodhisattvas, guardian deities, and devas fused Hindu, Buddhist, and Tibetan Bon influences into a colorful and intricate display. A number of vividly colored illustrations can be seen in several ancient Buddhist manuscripts in the gallery.

There is only one exhibit that depicts the Buddha’s mahaparinirvana at Kushinagar alone. Shakyamuni lies on his right side in the lion posture between two sal trees. His faithful attendant Ananda is seated on the floor, and though his face cannot be seen, we can sense the heavy weight of sadness hanging over him. With his final words, “All composite things are perishable. Strive for your own liberation with diligence,” the Blessed One passed away.