Devout Patrons of Buddhist Art, on view at The National Museum of Korea in Seoul from 23 May to 2 August, is a special exhibition exploring Buddhist sculptures, paintings, sutras, bells, reliquaries, and ritual artifacts offered by different social classes, from the king and the nobility to monks and commoners. Unlike a typical period-centric exhibit, however, this one focuses on the single theme of “Prayer” (發願)—the most fundamental driving force behind the creation of religious art.

While “prayer” basically means hoping and seeking to fulfill one’s personal wishes, in Buddhist terms it is making a vow from the perspective of a bodhisattva to lead all beings to enlightenment. Constructing a temple, enshrining an iconic painting, and publishing sutras are all means to disseminate the Buddhist teachings and to practice good deeds for the benefit of both oneself and others. When patrons prayed for their own enlightenment, their personal wishes for their present life were also a vital part of their prayer. The most common wishes were for the longevity and welfare of family and relatives, for peace and prosperity for the nation, and for all beings to achieve enlightenment or rebirth in a Pure Land.

The exhibition is divided into five parts: “Significance of Buddhist Patronage,” “Kings and Aristocrats: Publication of Sutras,” “Statues Produced by Patrons of Every Class,” “Women of the Royal Court as Major Buddhist Patrons,” and “Monks and Ordinary People.” In the first part, “Significance of Buddhist Patronage,” one encounters artworks representative of the Three Kingdoms period (57 BCE–668 CE) and the Unified Silla period (676–935), such as gilt-bronze sculptures and exquisite reliquaries. It provides a good opportunity to compare the different stylistic characteristics of each of the three kingdoms. While the style of the Goguryeo is powerful and masculine and the works have sharp and decisive lines, the artworks of the Baekje Kingdom are feminine and soft and elegant. The Unified Silla absorbed all of the merits of the Three Kingdoms style and integrated the Chinese Tang dynasty (618–907) style to create a harmonious and sophisticated international style. On display are the reliquaries excavated from the existing (west) stone pagoda of the Mireuk Temple site in North Jeolla Province (Baekje Kingdom period, 639; National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage), which attracted nationwide attention in 2009 following their recent discovery. The inscription on the golden votive tablet of the reliquaries clearly indicates when and for what purpose the temple and the pagodas (east and west) were built:

“We pray! Let the memorial offerings and good deeds last forever so that the king’s life be solid as a mountain and the throne be permanent as the heaven and earth. Let the right law expand greatly above and let the people be enlightened below. Again we pray! Let the queen’s heart reflect the realm of the Buddha like pure water. Let her body be like a solid diamond so it will not diminish, like the Dharmakaya. Let everyone enjoy blessings and benefits forever. And let all the people enter the world of Dharma [Dharmadhatu].”

During the Three Kingdoms period, the royal court was the major patron of religious art. The temples and pagodas constructed at that time not only symbolized prayers for peace and well-being, but also demonstrated the authority of the king and his political power.

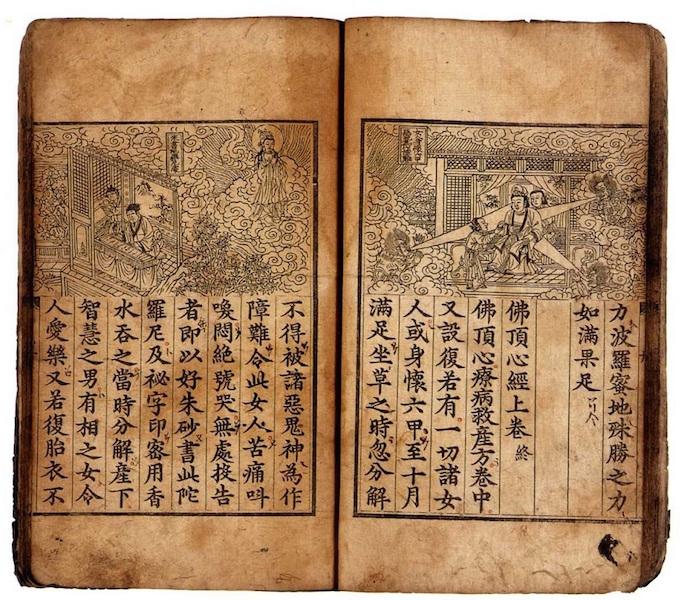

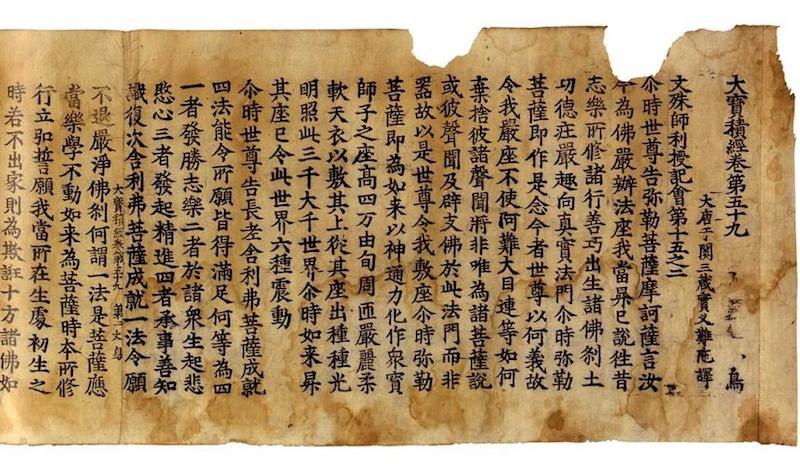

In the second part of the exhibition, “Kings and Aristocrats: Publication of Sutras,” one encounters the famous Goryeo period (918–1392) Tripitaka sutra prints that were made with the intention of using the Buddhist Law to protect the country against foreign invasions. On display are the Maharatnakuta Sutra (Great jewel accumulation sutra), volume 59 of the first edition of the Tripitaka Koreana (Goryeo period, 11th century, woodblock print, handscroll, National Treasure No. 246; donated by Song Sungmoon), and the encyclopedia Jinglü yixiang (Peculiarities of the sutras and vinayas), volume 8 of the second edition of the Tripitaka Koreana (Goryeo period, 1243, woodblock print, concertina book, Treasure No. 1156; donated by Song Sungmoon). The Tripitaka Koreana was produced twice during the invasions, once in the early 11th century during the Khitan invasion and again in the mid-13th century during the Mongol invasion, the first set of woodblocks having been destroyed by fire during the Mongol invasion, in 1232. The revision and recreation of the Tripitaka was ordered by King Gojong (r. 1213–59); many people participated in this massive project, and the carving took 16 years to complete. Minister Yi Gyu-bo wrote a national prayer for the king at the time, which motivated both the nobility and the common people to participate in the work:

“We prostrate with sincere devotion. All the Buddhas, saints, and heavenly devas, please listen to our fervent prayer. Endow us with tremendous ability to chase the evil barbarians away and to prevent our land from being encroached on again.”

The royal court often attempted to unite the people with a common prayer when the country was under the threat of foreign invaders. The engraving of the Buddhist scriptures in their entirety on woodblocks is a good example. The extant Tripitaka Koreana, a UNESCO World Heritage article, consists of no less than 81,350 wooden blocks.

Because the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910) was an era when Confucianism prevailed and Buddhism was oppressed, the royal court could not freely conduct Buddhist rituals inside the palace and the king could not officially participate. Hence, in the early part of the period, women from the royal household such as the queen spearheaded the funding of Buddhist services and became the religion’s main patrons. Even though it was a period of repression, they frequently sponsored the printing of Buddhist scriptures and paintings for their husbands and sons, who often became the victims of factional disputes in the royal power struggles.

The Fodingxin tuoluoni jing (Ushnisha-Dharani sutra) (1485, woodblock print, Treasure No. 1108; Horim Museum) ordered by Grand Queen Insu for her son, King Seongjong, contains powerful mystic dharani to protect him from disaster, and Queen Inmok copied the Suvarnaprabhasa Sutra (Golden light sutra) (1622; Dongguk University Museum) herself and decorated the cover with embroidered lotuses. A delicate feminine touch has been added to the sutra in the form of a sincere prayer that her deceased father and son be reborn in paradise and that the surviving family members remain safe and unharmed. The last part of the exhibit deals with artifacts from the late Joseon period. Rather than being sponsored by the royal court, at this time most Buddhist offerings were made with the collective finances of monks and common people. During the wars against Japan (1592–98) and the Manchu (1636–37) a great number of people were killed, and the temples played a key role in holding rituals for the souls of the deceased. For this purpose, very large Buddhist paintings, some as long as 10 meters, were commissioned for outdoor ceremonies such as Suryukjae (the “Wandering Spirits” ceremony).

Representing the history of prayer through the ages, this outstanding show is a great opportunity to experience these Buddhist masterpieces from this unique perspective.

Soyon Kang is an associate professor at Hongik University in Seoul, specializing in Korean Buddhist art.