. . . painting is something that takes place amongst the colours… one has to leave them alone so that they can settle the matter between themselves.

(Rilke, 66)

Last summer my husband and I were planning a trip to London. We were due to run a promotional event for my book, Bringing Mindfulness to Life, at the Triratna Buddhist Centre in Bethnal Green, and looking forward to combining it with seeing friends and enjoying some of the cultural offerings of the city. We had booked tickets for a proms concert and I was particularly looking forward to see the art exhibition “Momentarium” at the Lisson Gallery, by a painter I had increasingly come to admire, Christopher Le Brun. I was/am enchanted by his work, the freedom from irony, the immediacy and presence. I resonate with the aliveness and confidence of the gestures and the attitude of open-ended, unselfconscious playfulness—all qualities to which I aspire in my own artwork and meditation. I had been studying his work online and was full of anticipation to meet the large, luminous, almost wall-size canvasses in person. But in the end, I never got to see his work: our visit coincided with the most intense heatwave the UK has ever encountered, and all trains south were canceled—the railway tracks had buckled in the heat.

I am often impelled to write about the connection of mindfulness and the climate emergency, which is really the huge underlying challenge of our times. But I promised a part two to my previous article on Layered Simplicity, which investigates the overlap of meditation and creative art-making. Last time, you may remember, I presented some guiding principles pertinent to both domains:

• Connect with your intention and hold it lightly

• Trust the rhythm of your momentum

• Let it all be quite ordinary and sense-based

• Loose yourself

Now, here is another piece of advice, pertinent to the conundrum of where to focus one’s creative energy in the face of so many alarming and pressing concerns:

• Trust that you are making a contribution

It may not appear like that in an immediately obvious way: how is spending countless hours on your cushion or filling reams of pages with words or paint useful for the survival of life on Earth or achieving greater social justice? Well, I firmly believe that the qualities you are cultivating in those ways are transferrable and are needed for resourceful, courageous, authentic, and meaningful living. To give just one example: when you are engaged in meditation or creative making, you tend to be focused on one thing for a prolonged period of time, unavailable to the attention-grabbing media distractions that otherwise ceaselessly flicker in front of your eyes, undermining your continuity of purpose. You are more likely to bring this one-pointed attention to anything else you do and others will pick it up by being around you, or by exposure to your artwork, writing or other creative expression.

• Draw on collective intelligence—learn from and with others.

You may engage in your chosen art in mostly solitary ways or collaborate with others. In either case, you don’t have to be cut off from the immense resource of collective intelligence. Neuroscience is now less interested in treating the brain as a single entity, but in how “intelligence arises within the brain-body system as a whole, and between a group of minds that influence each other. . . . Ideas can hop from brain to brain and become seeded in collective ways of thinking.” (Critchlow, 5)

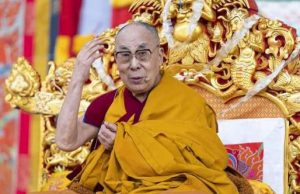

Most people find meditating with others a great support—our minds are synchronized and buoyed in a shared energy field. This experience of interconnectedness is not even dependent on being in the same room at the same time. You can give your meditation a great boost when you bring to mind your sangha: friends, teachers, and archetypal figures that give you, in somewhat mysterious ways, direct access to shared states of calm, insight, joy, and so on.

There is not much point trying to be original, but a lot to be gained from studying the masters of your discipline and channeling their influence. Try to meditate like a buddha, paint like your favorite artist of the moment—you can guess who mine is, or write like Margaret Atwood. Luckily Christopher Le Brun has a rich and well-constructed website, and I have been watching him speak about his art in some of the listed videos. I would like to introduce you to some of his insights and draw out some implications for the life of meditation and my own art-making. This is my way of tapping into collective intelligence, opening into the wider network of shared experience and insight.

I put art into a place where it doesn’t need explanation. It can be surrounded by thoughts and references, but it doesn’t need justification. That would take away from what’s mysterious about it.*

There are well-documented physical and mental-health benefits to meditation, but my guess is what keeps people engaged in long-term practice is much more unfathomable. When we meditate, we escape the narrow, neat labelling and effective organizing that characterizes much of our material functioning and make space for other dimensions of being.

Intelligence in painting is not cleverness—it is to do with the senses, the judgement of one’s hands. Your hand develops memories of doing things that have their own truth. . . . Painting is a sensitive record of touch.

Meditation starts with the body. Will Johnson, an expert on meditation posture writes:

By kindling an awareness of sensations, accepting them exactly as they appear, and then yielding to the current of change that can be felt to animate them, we create a stable base from which we can then expand outward, including the ever-changing sounds and sights in the world around us in a condition of mindful awareness.

(Johnson, 14)

The body carries the imprint of our lived experience and if we ignore it, our experience rests on thin, shaky foundations. When I paint, I often listen to music—it helps the body to stay loose and responsive, letting the action become dance-like.

When I use a brush, there is a bit of me in it and a bit of accident.

I love that: a bit of me and a bit of accident. The “bit of me” in meditation might be some kind of decision; a conscious orientation toward the breath, or kindness, or remembering something for which I am grateful. Or it may be a decision to give some space to the gentle exploration of a difficulty. From there, things just happen in unforeseeable ways, and I am doing my best to be present for that unfolding.

I am painting moments. The fact that I don’t know what it is, doesn’t matter. . . . If you carry out an idea you had previously—that’s boring. Painting is so extraordinary all the time—I love to watch it happening before my eyes.

Like Le Brun, my go-to gesture in painting is the simple vertical stroke, like an out-breath, and it will be repeated, again and again, building a continuity of presence.

You could create anything from your imagination—you could choose joy, unless you are embarrassed by it.

Mindfulness has a mirror-like aspect, an objectivity that can appear cool and detached. Maybe that’s why it fits in well into our modern culture, which is characterized by cynicism about anything religious or too blatantly positive. But is joy not what we secretly aspire to? Try smiling next time you meditate.

The worst thing of all is the beautiful passage of painting. The beautiful bit has to go. The moment I let go, I start to say what I really mean.

I kind of know what he refers to here: holding onto some precious little corner can interfere with the direction the painting or the meditation wants to take. But I also think it’s okay to celebrate the successes during the process. The layers of the work are created by making choices: keeping or enhancing what you like and painting over what seems to detract. And the traces of those undesirable elements are important, they are what gives a richness of texture, a gritty vitality.

What has to go, both in making art, writing, meditating, or any other creative pursuit is the attachment to an outcome that reflects on “me.” Le Brun’s work communicates that spirit of freedom and risk-taking, openness to the unknown. He says something interesting and insightful about the finishing point of a painting; he will ask himself the question:

Is the painting independent of me?

At a certain point in meditation, it sometimes becomes clear that that nothing more needs doing; “you” can have a rest. Then one can allow the spontaneous play of appearances to unfold. The great eighth century Buddhist master Padmasambhava put it like this: “Like clouds in the atmosphere that are self-originated and self-liberated, you should look at your own mind to see whether it is like that or not.” (Padmasambhava, et al.)

. . . If they are suited to leave the studio, if they’re ready to go, it’s a good feeling.

Likewise, it’s a good feeling to end a meditation—or an article—by considering it a gift to the world, independent of “me.”

* All the quotes are my transcriptions of Christopher Le Brun’s words in the films on his website. They may not be 100 per cent accurate.

References

Critchlow, Hannah. 2022. Joined up Thinking: The Power of Collective Intelligence to Change Our Lives. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Johnson, Will. 2000. Aligned, Relaxed, Resilient: The Physical Foundations of Mindfulness. London: Shambhala Publications.

Rilke, Rainer M. 2002. Letters in Cézanne, Joe Agee trans. New York: North Point Press.

Padmasambhava, et al. 2010. Self Liberation through Seeing with Naked Awareness. New York: Snow Lion

Related features from BDG

Abstract Meditations and Artistic Contemplation, with Françoise Issaly

Sculpting Silence: The Artistic Meditations of Elizabeth Turk

In a Moment, in a Breath: 55 Zen Meditations from Roshi Joan Halifax

Art as a Contemplative Exploration of Reality – Recent Works from Visionary Laurie Anderson

The Art of Mindful Looking

Dance for a Passing World