As livebloggers go, the Korean monk Kim Gyo-gak is far from typical. According to Wikipedia, he was born more than 1,000 years ago, encountered Buddhism on a trip to China, became a monk on his return to Korea, then returned to China in 719 to cultivate himself deep in the wilds of Mount Jiuhua, in Anhui Province. He took the name Jijang (Skt: Ksitigarbha) and lived there as a hermit until his death at 99 years old.

When the nobleman who owned the mountain where he practiced offered to build him a temple, Jijang convinced his aspiring benefactor with a magical gesture to cede the entire mountain to the Dharma, and thus his bodhimandala became one of the four sacred mountains of China. There are reputed to have been more than 300 temples there in ages past, although only 95 are said to remain.

A few years after Jijang’s death, his tomb was opened and he was discovered to have left behind a well-preserved mummy, which is still on display at his monastery today. Jijang is revered as a manifestation of Ksitigarbha, the bodhisattva who vowed to protect beings between the death of Shakyamuni Buddha and the birth of Maitreya Buddha, including those in hell. Indeed, these days he is particularly associated with the dead—and in Japan, as Jizo, even more so with children who have died.

You can often find statues of Ksitigarbha in Chinese Buddhist temples, in the chapels where funerary plaques are displayed, or in Japanese cemeteries.

Somehow, his story has come down to us through the ages, as have other tales of the Great Bodhisattva, Earth Store Ksitigarbha. They are like the pure ring of a bell across the valley of time. Amid the suffering of the modern world, that sound is often hard to hear over the cacophony of our everyday conversations.

Another snippet of Buddhist lore that comes to mind is that Bodh Gaya, the ultimate bodhimandala, sits cosmologically directly above the Avici Hell, a cube of some 20,000 yojanas on a side, reserved for those who have committed the worst of sins. That’s approximately 300,000 kilometres on a side, so it must hold a lot of us.

Hell now seems uncomfortably close and not just some mythological place. We find ourselves in the midst of a pandemic that has shattered our habitual belief that we control the world. For tens of millions of us, COVID-19 has sickened and killed our loved ones. For untold millions more, the warp and weft of life as we knew it has been irrevocably torn asunder. Like gods facing their demise on the Wheel of Birth and Death, each of us stands on a precipice, looking around at how our fellow citizens are facing the same crisis we see. The outcome is far from certain.

Looking around, we can’t help but notice those around us. Some are giving 110 per cent for the welfare of others around them, duty-bound to serve, but finding the sacrifices overwhelming. Sometimes those people being helped or potentially going to need help are unable to forego their own license—confused with liberty—for the benefit of their own future safety or the safety of others around them. Yet another group is cruel and quite willing to push others over the edge if it means more left over for them. It’s the bodhisattvas I choose to emulate.

Maybe human nature hasn’t changed much since Jijang’s time, but in the Anthropocene, the scale of it all is so much to take in. And therein lies the kōan: fairytale Buddhism, or simply replaying “The Buddha’s Greatest Hits,” is simply unfulfilling. How does one practice the authentic Royal Road of cultivation, here and now?

Of late, I’ve arrived at the conclusion that nobody has the definitive answer, or even that there is one definitive answer. The answer can only be found in the symphony of billions of melodies. I recently stumbled again over Roshi Bernie Glassman’s dictum: “Not knowing; bearing witness; taking action.” It struck me to such a degree that I wrote it on the whiteboard by my desk and ponder it daily.

Now that I have committed to write another cycle of monthly columns for Buddhistdoor Global, I have nothing to offer in the way of answers. I can only offer a reporter’s notebook, dedicated in the spirit of Ksitigarbha to looking unblinkingly at today’s challenges with the Dharma eye.

In the last cycle, I focused on environmental issues and I will continue to do so, but I hope to broaden my scope to include the emerging field of Buddhist chaplaincy and other ways that Buddhists engage with the non-Buddhist world. This is where I see the future of Dharma practice, and it is a very open conversation in which we Buddhists need to listen more than we speak, and in which we need to tend the commons alongside our fellow inhabitants of the planet rather than insist on cultivating our own private hermitage.

I am writing this in the hopeful fresh days of 2021. Here are just a few of the remarkable people whose conversations, carried like the ring of Ksitigarbha’s bell across the ether, have sustained me of late, and whose perspectives I hope to share with you in the coming year.

- Rev. Dr. Monica Sanford has published a guide to Buddhist chaplaincy, Kalyanamitra: A Model for Buddhist Spiritual Care, Vol. 1. She’s working on volume two for late spring of 2021.

- Linda Hochstetler, a Toronto social worker specializing in grief work, is writing a Canadian guide to dying, infused with her Kagyu Buddhist sensibilities.

- Richard Bryan McDaniel, chronicler of all things Zen, continues to nurture tendrils of history in the making around us.

- Shinko Roshi leaps out of the Zen tradition into a fusion of womanist, Vajrayana, and Earth-honouring practices.

- Ajahn Sona models environmentally sound practices at Birken Forest Monastery in the British Columbia interior.

And of course, I hope to reach out to other Buddhists as well, to explore how they are practicing in the here and now.

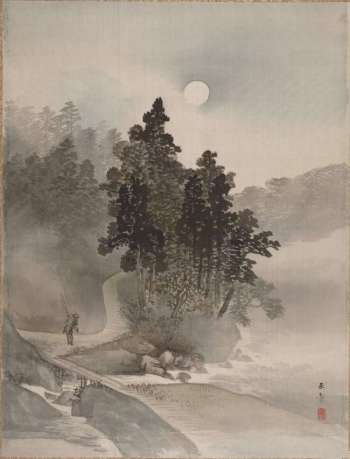

Another image springs to mind: an old Japanese woodblock print of a lonely pilgrim on a dark indigo road, holding a paper lantern out ahead at the end of a stick on a moonless night. Very little outside the faint, close glow that the lantern casts can be deciphered through the mist. Let’s walk with him a while.

Very Beautiful.