The ancient Japanese city of Kyoto has many ancient Buddhist temples, but Kiyomizu-dera, or the Temple of Pure Water, has for centuries been one of its most visited Buddhist sites and in 1994, the United Nations named it one of the monuments in a Kyoto-centered UNESCO World Heritage Site. Located in the district of Higashiyama, the Eastern Hills, the uniquely structured temple has been a magnet for pilgrims and travelers for more than 1,000 years, in part because of the popularity of its principal deity, the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (Jpn: Kannon). Although it has long served as center for Buddhist worship with Kannon at its core, Kiyomizu-dera has captured the attention and imagination of the Japanese people as a place of natural beauty, legend, and wish-granting. As such, it has featured prominently in the literary, theatrical, and artistic traditions of Japan.

According to legend, the history of the temple dates to the eighth century, when a Buddhist monk, Enchin, dreamed of a golden river flowing down Mount Otowa above Kyoto. When the monk went to the place of in his dream, he encountered an old man sitting on a log praying to the bodhisattva Kannon. After the old man had departed, Enchin realized he should carve an image of Kannon from the wood. He worked on it for many years and only when he met the warrior Sakanoue no Tamuramaro (758–811), who was impressed by his dedication and became his patron, was he able to perfect the image. Tamuramaro then founded a temple in 778 to house the image of Kannon. Enchin was a monk of the Hosso (Skt: Yogacara) school of Buddhism, which teaches that our understanding of reality comes from our own mind, rather than actual empirical experience, so the temple has historically been affiliated with this school. The temple’s principal deity—created at a later date in gilded wood—is Senju Kannon, a form of Avalokiteshvara with 1,000 arms and 11 heads, a representation of the deity that represents his ability to see in all directions and use all means to aid sufferers.

Centuries after its original construction, the temple complex was destroyed in fires. It was rebuilt in 1633 under Tokugawa Iemitsu (1604–51), the third of the Tokugawa shoguns who ruled Japan from 1600–1868. The complex is made up of 30 buildings, including a three-story pagoda, or reliquary, that is one of the tallest of its kind in Japan at 31 meters. The temple’s main hall, or hondo, is a massive wooden structure that houses the principal Kannon image. Extending outward from the hondo is an extensive verandah that was built to accommodate the many pilgrims visiting the main hall. It has the appearance of a large wooden stage that juts out of the hillside at a height of 13 meters and is supported by a lattice of massive vertical pillars and horizontal beams, said to have been erected without the use of a single nail.

The verandah offers the temple’s many visitors a spectacular view of Kyoto and is crowded throughout the year, but especially during cherry blossom season in spring and maple-viewing season in the autumn, as shown in the first photograph. However, the temple also appeals to visitors and artists alike in the winter, when the bold geometry of its architecture contrasts with the softness of the surrounding snow-laden trees. Kyoto artist Tokuriki Tomikichiro (1902–2000) captured this serenity in his print from c. 1930.

Sakura by Yoshu Chikanobu, Japan, 1884. Full-color woodblock print.

Collection of Scripps College, Claremont. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Ballard

In the Edo period (1600–1868), however, the verandah was the site of some practices that were far from serene. At that time it was believed that surviving a jump from the temple’s verandah ensured that one’s wishes would come true. Apparently more than 200 people attempted the jump and over 80 per cent survived. This practice was prohibited in 1872, but it gave rise to Japanese phrase “to jump off the stage at Kiyomizu,” which is similar to the English expressions “to take the plunge” or “a leap of faith.”

The print shown here by Yoshu Chikanobu (1838–1912), depicting a beautiful young woman jumping from the verandah, illustrates a very different and tragic leap from a legend that was popularized in an Edo-period kabuki play from 1817 called Sakurahime Azuma Bunsho. According to legend, Seigen, a Buddhist monk at Kiyomizu-dera, had once loved a young acolyte, and he and the boy had vowed a double suicide by leaping off the verandah at Kiyomizu, but Seigen had not followed through. Later, when Seigen met Princess Sakura, he believed her to be the reincarnation of his lover and she fell in love with him. In certain versions of the legend, Seigen was killed and Princess Sakura too committed suicide by jumping off the balcony into the valley below—surrounded by cherry blossoms.

Kiyomizu-dera. Photo by the author

Lower down in the temple complex and beneath the main hall and verandah is the Otowa waterfall, or Otowa no Taki, supposedly the golden river of Enchin’s dream and the source of pure mountain spring water and the temple’s name. Today, three streams of water are channeled downward into a pond, and visitors take turns to file along a platform behind the waterfall and catch water in metal scoops to drink. The pure water has long been believed to have wish-granting powers, which explains why there is always a long line of visitors waiting for a chance to sip the water.

The Otowa waterfall also appears in several Japanese legends, most notably in those of the ninth-century poetess Ono no Komachi (c. 825–900), whose beauty, deeds, and romantic relationships became fodder for seven distinct legends concerning incidents in her life that became the subject of the Nanakomachi (Seven Komachi) Noh plays. In the 19th century, woodblock print artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798–1861) created several series of prints related to the Nanakomachi, often depicting kabuki actors or contemporary courtesans and beautiful women in the role of Komachi. In the below print, a contemporary beauty represents the poetess standing beside the Otowa waterfall. According to one of the legends, Komachi would secretly meet at the falls with the Bishop Henjo (816–90), a fellow poet with whom she is known to have enjoyed a poetic banter—and perhaps a romance. According to other legends, Komachi is said to have been a manifestation of the bodhisattva Kannon, so her appearance on the temple grounds would be natural.

Japan, 1851. Full-color woodblock print, 4-1/2 x 9-7/8”.

Collection of Scripps College. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Fred Marer

woodblock print, 14-1/4” x 9-7/16”. Scripps College, Claremont.

Gift of Mrs. Frederick S. Bailey

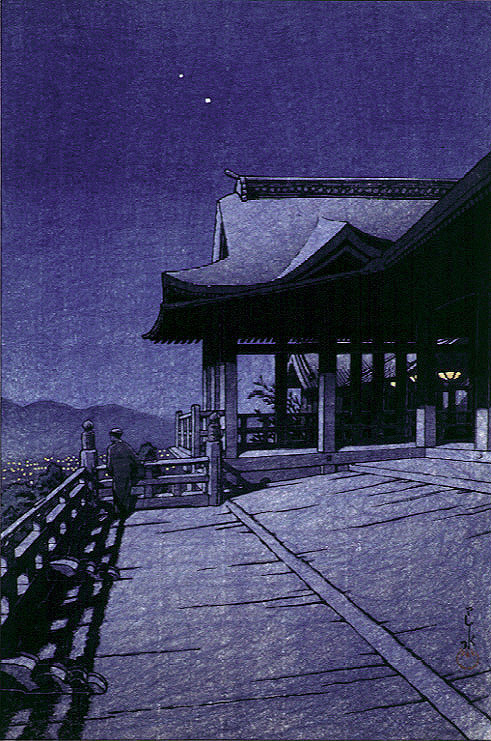

In a final woodblock print by Kawase Hasui (1883–1957), a master landscape print artist of the 20th century, we are presented with a rather rare portrayal of Kiyomizu Temple in the gentle evening moonlight. Rather than focus on the complex structure of pillars and beams that support the verandah (though he perhaps hints at it in the crisscrossing shadows of the railings cast by the moon to the left), the artist depicts the upper section of the verandah, now empty of the crowds of pilgrims and travelers. A lone, unidentified figure stands at one corner of the railing gazing out across the hillside toward the city below. Its many windows are lit with oil or gas lamps that shimmer in the distance like tiny stars. Even with all the legend, drama and tragedy that has been associated with the temple over its long history, Kiyomizu-dera can still be a place of tranquility and reflection.

very helpful for our upcoming trip to kyoto1!!1!111!!!!!

can you tell me please the bibliography?