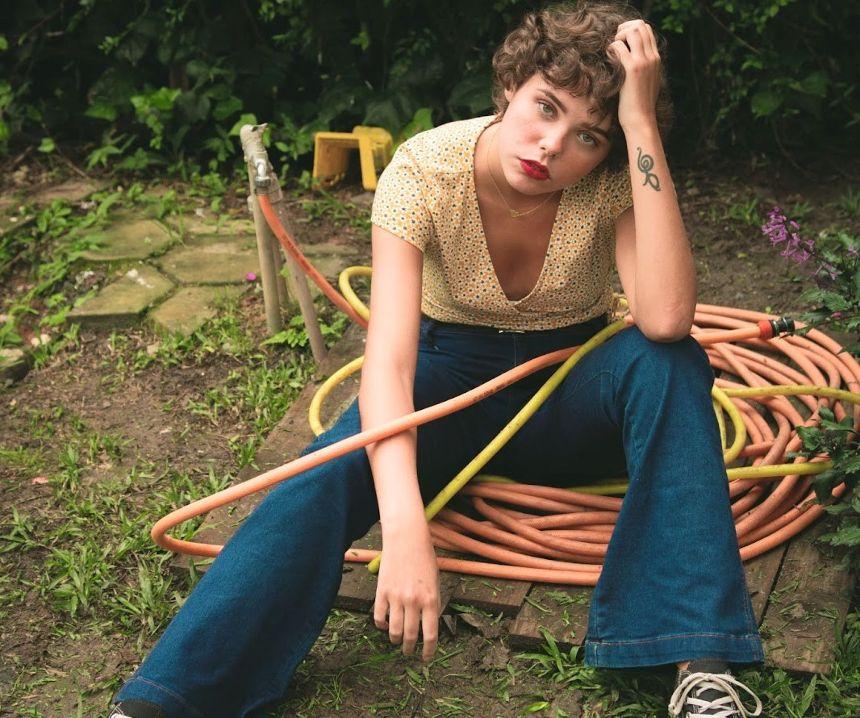

As we move into late spring, the rainy days of April have been replaced by the bright, sunshiney days of May. The grass is long, the birds are singing, and the garden needs to be watered.

Fortunately, our homestead operation is small enough that our watering needs can be managed through the use of a garden hose. Unfortunately, the rubber garden hose I purchased at the hardware store doesn’t always function as intended. Don’t get me wrong, it gets the job done. The hose doesn’t leak, and it holds up in inclement weather. However, it seems to be prone to getting kinks in the line whenever I drag it around the property.

Something about the natural twistiness of the rubber causes it to fold in on itself to the point that its water can’t reach the end of the line, resulting in a few, sad drops of liquid coming out of the hose. So I must spend several minutes each time I want to water the garden walking the length of the hose to remove any kinks. This is made doubly hard by the fact that removing one kink from the hose often results in two more forming nearby!

This can be frustrating at times, but patience and a few deep breaths allow me to remove enough of the kinks that I can go about my day. The plants receive the water they desperately need, the hose is—temporarily—kink-free, and everyone is better for it.

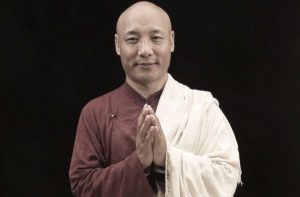

Our Buddhist practice is a lot like removing the kinks from a garden hose. Oftentimes, we sit on the cushion with the expectation that things will quickly fall into place. We have the “right” teacher, we purchased the expensive meditation cushion, and we’ve watched countless YouTube videos designed to help us realize enlightenment. But when we actually start to chant, meditate, and study sutras, we notice that things don’t flow as they should.

Perhaps the sutras don’t make sense to us because of their iconic imagery. Maybe the rockstar Dharma teacher loses a bit of their appeal upon close inspection. Perhaps sitting in silence with our thoughts is more unpleasant than we thought it would be. In any event, we find “kinks” in our spiritual practice in the same way that a gardener might find kinks in a garden hose. And these kinks can become more and more frustrating as they stop us from manifesting our buddha-nature in daily life.

However, it’s important to put things in perspective so that we don’t become discouraged.

In the same way that the natural bendiness of a garden hose causes it to form kinks, the defilements—greed, anger, ignorance, and so on—that we have as humans naturally cause kinks to form in our spiritual practice. This is to be expected, and it should not be taken as a sign that we are doing something wrong. Instead, we should look at these kinks as an opportunity to practice harder, and a reminder that more prep work is needed before we dive into the heady waters of Buddhist spirituality.

Of course, what that looks like in practice will differ for each person. It’s possible that we may need to find a new teacher who better fits our expectations, or we may need to study sutras with friends so that we can have our questions answered. Perhaps we must make peace with the fact that our minds are not the calm, tepid pools of tranquility that we envisioned.

The kinks and their cures may manifest in various ways, but there are two key things we must do to ensure they do not hinder our path to enlightenment. First, we must accept that they are there. Second, we must form strategies to deal with them.

For example, one kink in our spiritual practice may be that we have a hard time finding time to meditate during the day. It may be that we always wake up with the intent to spend time in single-pointed concentration. But it always slips our mind until the moment right before we lay down to go to sleep.

If this happens more than once, we may be tempted to either give up on maintaining a daily meditation practice or beat ourselves up for not having the discipline to stick to one. But both of these paths are folly.

Instead, it’s better to acknowledge the kink in our spiritual garden hose and make plans to fix it. In this case, we might shorten our meditation time a bit and move it to a part of our day when we are less busy. We might also tell the people in our lives that we’re reserving that time for Buddhist practice so they don’t disturb us.

In this way, we can remove the kink in our spiritual garden hose so that our Buddhist practice can flow freely through our life.

Namu Amida Butsu

Related features from BDG

Dharma’s Garden – Nourishing the Local Community through Homesteading

Can Small Farms Save the World? Part Two: Forest Gardens

We Are the Flowers in the Garden

Right Mindfulness and Vegetable Gardens

Grow Your Garden: A Simple Practice in Reflection, Part One

Mindfulness Practice in Japanese Stroll Gardens

A Buddhist Garden of Peace in Rural Montana