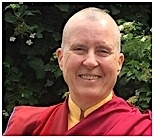

There is a Western Tibetan nun presently working to establish a Tibetan Buddhist nunnery in the US state of Maine. Khenmo Konchog Nyima Drolma is the abbess of the Vajra Dakini Nunnery, that is taking root in the coastal city of Portland, where no such nunnery has ever existed before. And while this ongoing task will take time, her determination is resolute, as is her deep commitment to the richness of monastic life, formed over many years of Buddhist practice.

The planned nunnery is in the lineage of Drikung Kagyu. According to the nunnery’s website, “The Drikung Kagyu order was founded in 1179 by Kyobpa Jigten Sumgön. It is headed by the two Kyabgon Rinpoches: His Holiness the Drikung Kyabgon Chetsang and His Holiness the Drikung Kyabgon Chungtsang. While Chungtsang Rinpoche resides in Lhasa, Chetsang Rinpoche has established the Drikung Kagyu seat-in-exile in Dehra Dun, in northern India.

In order to lay the foundation for a long-lasting presence at the lineage’s new location, Khenmo says she is now looking at what monastics require and what Portland can offer, aiming to ensure that the nunnery provides for the needs of the nuns as well as those of the public.

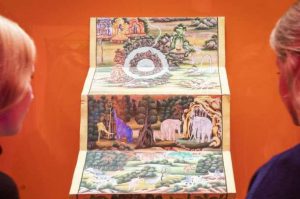

Khenmo has previously spent time in Dehra Dun, serving and training in Buddhist monasticism. A former art professor, she was able to offer her creative skills to her teacher in the form of a large-scale art project. Khenmo then spent a year creating a majestic piazza at the Songsten Library, which forms part of the Drikung Kagyu Institute.

“My teacher knew I was an artist, and he wanted the front of the library to be a piazza like in Europe,” she relates. Prior to this, she created an art and service program while an art and sculpture professor at Maine College of Art in Portland, so one could say that things have come full circle.

Monasticism, and Buddhist monasticism in particular, are not exactly a commonplace part of day-to-day life in the US, but interest and curiosity in the Buddha’s teachings is increasingly evident. Khenmo hopes that the eventual building will be both a welcoming place for Westerners exploring Buddhism, and a training place for those with an interest in becoming Buddhist monastics. But until the actual foundation of such a structure is realized, Khenmo is not waiting to go out within the community to serve and teach.

Khenmo says she finds Portland to be “a great place to get new ideas up and going,” and her enthusiasm is clear. She also feels that the current climate in the US lends itself to the growth of Buddhism, yet there is one aspect that she thinks has been under-represented: “It’s a creative period in the United States in terms of establishing Buddhist monastic centers.” She notes there are now many meditation centers open to lay Buddhists, yet few for Western monastic trainees. Khenmo shares her view that such monastic training centers should offer something to attract people who aspire to dedicate their lives to the monastic tradition.

Khenmo and others are discussing models that “fit and provide something that would attract others to offer their life.” She observes that many in the US are looking for a change and have a great interest in service, noting that she wants to enable those interested to have more ways to volunteer, to teach, to offer meditation instruction, and to commit to retreat.

So how is the new generation of Buddhist monastics in America approaching this challenge and opportunity? Khenmo knows firsthand that seeking Buddhist monastic training in the US can be difficult. In fact, in order to experience traditional Shedra training, she had to leave the US to go to Gampo Abbey in Nova Scotia, Canada, during the early days of her ordination in 1999. Since that time, the presence of Buddhist monastics in the US has increased, but support structures have yet to keep pace with their needs.

Today, a group of Western monastics meets yearly to support, share, and learn from each other. In her words: “Every year, Western monastics from all Buddhists lineages gather to share our wisdom and experience. We hold the gatherings at different monasteries and thus see the how each lineage has adapted to the West and what we are learning as Western monastics in the process. Historical and geographical prejudices have given way to understanding more of the richness of each tradition and respect for all the ways the Buddha’s wisdom is practiced. The Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering 2016 was at The Land of Medicine Buddha.”

Another of the ways that Khenmo seeks to live the Buddha’s teachings and grow her community will take place this September, when she joins and brings others to a Hunger Walk in support of Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi’s Buddhist Global Relief (BGR) efforts.

According to the Buddhist Global Relief website: “BGR holds annual ‘Walks to Feed the Hungry’ in cities and towns around the US and elsewhere, including Cambodia and India. A BGR walk brings together Buddhists from different communities under a shared purpose: to help people around the world escape from chronic hunger and malnutrition. A walk offers us the chance to express compassion in action in solidarity with the world’s poor. It’s also a great form of exercise and an opportunity to make new friends.”

Many temples have pledged to participate in the September walk, and Vajra Dakini Nunnery will be one of them.

Khenmo also visits local parks and beaches to teach meditation, and has even led a meditation group in the New York City subway. “The Tibetan system of training in bodhicitta emphasizes specific exercises to expand our capacity for loving-kindness and compassion. In these exercises, we work with imagining relating to first a neutral person and then a difficult person in the same way we do towards our most loved ones. Or we imagine breathing in their suffering and extending compassion on the outbreath. We try to gradually increase opening our hearts,” she explains. “In the subway retreats, we practice first on our cushions in the meditation hall and then walk to the subways to sit in meditation in the middle of all kinds of people, putting these meditations into practice as we sit quietly, noticing when our hearts are open and when they are closed. Going back and forth from the temple to the subway we are more at ease practicing in all situations and using all our daily interactions as compassion meditation! The response was wonderful as all could see city-living as a wonderful opportunity to practice!”

Using her deep experience, her creativity, and her commitment, as well as the support and wisdom of fellow Western monastics will undoubtably help to foster Buddhism on American soil. A motivation for seeding monasticism is to share “the richness of its life and what it can offer.”

For Khenmo, the question is how to expand the Buddhist teachings at this particular historical juncture, and open up the Dharma to those who may be new to Buddhist monasticism. To do this, she joins others who are reaching deep into their training and devotion to create new pathways of opportunity, which will in turn benefit not just the renunciants themselves, but the entire continent.

“How can we make the doorway more accessible? How we can use everything from our lineage to open the door wider?” she offers. And while Khenmo Konchog Nyima Drolma, abbess of Vajra Dakini Nunnery, seeks to answer these questions, she continues to serve the Dharma in both traditional and innovative new ways.

See more