The Japanese kesa is a garment rich in contradiction. Worn by austere Buddhist priests, these rectangular robes, or stoles, are constructed from some of the most sumptuous silk fabrics woven by textile artists. Traditionally, the garments are patched together by hand but feature a highly formalized structure and are laden with symbolic meaning. They are primarily outer garments worn to keep priests warm, but they can also be read like mandalas representing the Buddhist cosmos. Echoing the original creation of these robes in Japan’s temples, many kesa have been donated to Western museum and college collections. Decades ago, 16 of these robes found their way into the collection of Scripps College in the town of Claremont in southern California. These seemingly complex yet simple garments provide a unique understanding of the intersection of dress and devotion in traditional Japanese Buddhist practice.

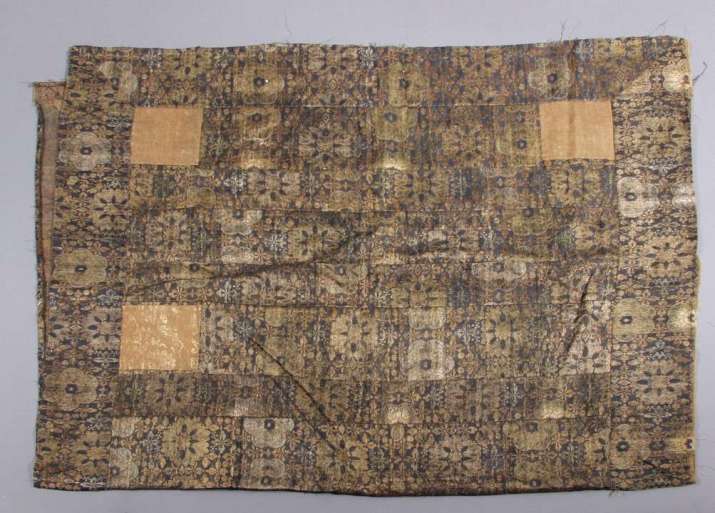

The Japanese word kesa (袈裟) is derived from the Sanskrit term kasaya, meaning “dark colored,” a reference to the yellowish-brown robes worn by early Indian Buddhist monks and the brownish robes worn by female monastics. Since the lay community traditionally dressed in white, the dark color represented the renunciation of the householder life. The original kasaya were single-layer garments stitched together by the monks from rags and discarded clothing of laypeople and then dyed using roots, bark, flowers, and twigs, particularly that of the jackfruit tree. The dark color and patched structure distinguished the early Buddhist community and deterred theft of the garments since they were easily recognizable.

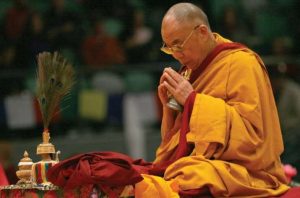

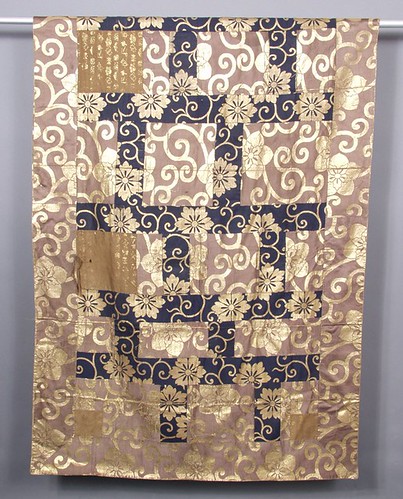

Although Buddhist followers in India were comfortable in a single garment, in the colder climates of China and Japan, monks wore several layers. In Japan, since at least the Heian period (794–1185), the kesa has been worn by Buddhist priests as their outermost robe, draped over the left shoulder and attached under the right armpit. While originally functioning as protection against the cold, it also served as a signal of the wearer’s Buddhist faith, and became increasingly elaborate over the centuries. During the Edo period (1600–1868), many kesa worn by priests of the various Japanese Buddhist traditions were patched together from silk brocade fabrics—often featuring gold threads—that were donated to the temples by members of the aristocracy, ruling military class, or wealthy merchants. By donating fabric to the Buddhist clergy, the lay community earned religious merit, and by stitching the fabric into a patchwork robe, the monks concentrated their attention on the creation of a devotional work of art, every stitch part of an act of meditation on the teachings of the Buddha.

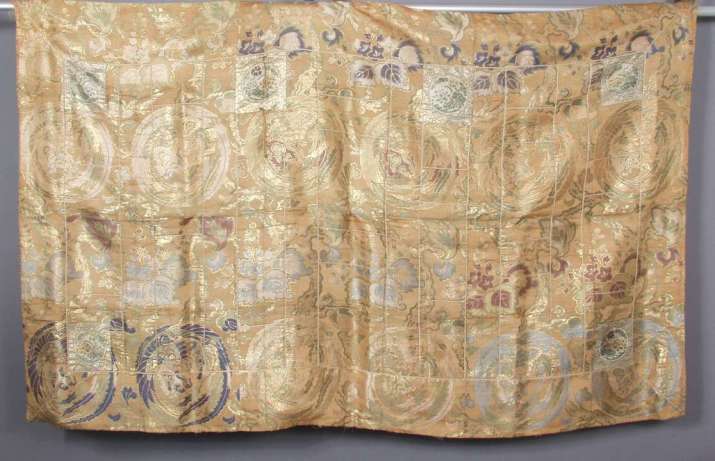

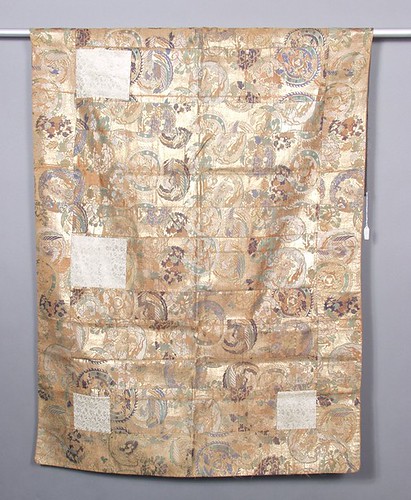

The kesa is basic in form, with no sleeves or collar. As such, the garment embodies the Buddhist concept of formlessness and the “unborn,” hinting at the hidden potential in all beings to attain enlightenment. However, this simple form also contains a complex and potent pattern. The squares of cloth are patched together to represent the entirety of the Buddhist cosmos in a structure that is reminiscent of mandalas—the geometric diagrams that are used in Buddhist visualization practices to represent the realm of enlightened beings. In kesa, cloth squares of varying sizes are patched together to form a border surrounding a central section. The center is organized into a series of columns or stripes, ranging in number from five to 25. The number of stripes indicates the wearer’s rank and the occasion for which it was worn, the highest number of stripes usually only being worn by an abbot during festival ceremonies. Most kesa, such as those featured here from the Scripps College collection, consist of seven columns. Known as Shichijo-gesa (七条袈裟) or “seven-striped kesa,” this type was meant to be worn by monks while in training or participating in ceremonies, according to the writings of Dogen—the 13th-century Japanese Buddhist monk who founded the Soto school of Zen Buddhism.

On many of these kesa, there are four or six patches in the central section that contrast in color with the rest of the garment. You can see it in the above image of the blue silk brocade kesa with gold and red patches. The four smaller squares in the corners of the central section represent the Four Heavenly Kings (Japanese: Shi Tenno), the deities who guard the four cardinal directions of the Buddhist cosmos. The two larger squares in the upper-middle section represent two compassionate bodhisattvas who flank the central column of the garment, a space that serves as an even more abstract representation the Buddha and his teachings.

When a monk wears a kesa, he is essentially wearing a mandala, an illustration of the Buddhist cosmos and a powerful sartorial symbol of his adherence to the Buddhist faith. More specifically, his sect and rank are indicated by the color and patterns of the garment. For example, in certain orders of Zen Buddhism a deep purple was reserved for senior monks and abbots. Certain patterns in the silk fabric also indicate particular sects, such as the phoenix roundels in the first kesa illustrated above and the one below. This fantastic bird, which in many cultures has signified resurrection and rebirth, has long been associated with the Jodo, or Pure Land school of devotional Buddhism, in which followers pray for rebirth in the Amida Buddha’s glorious Western Paradise.

Although these robes have existed in the context of Buddhist practice in Japan for centuries, interest in them as works of art is relatively new in both Japan and the West. In 1996, the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria in Canada held what may have been the first Western museum exhibition of these sacred garments, and in 2010, the Kyoto National Museum held the first museum exhibition of kesa in Japan. In the United States, the first major exhibition was probably at the Art Institute of Chicago in 2016. Scripps College, which owns the kesa featured here, has owned them for about 70 years, so though small, the collection is significant and represents a relatively early interest in this art form by Western collectors. As the donation of these textiles occurred before accurate records were kept at the college, we are uncertain of the identity of the donors, but the gift of such robes to an academic institution where they can be studied to encourage an understanding of Buddhism would surely lead to good karma.

See more

Scripps Collection Highlights (Scripps College)