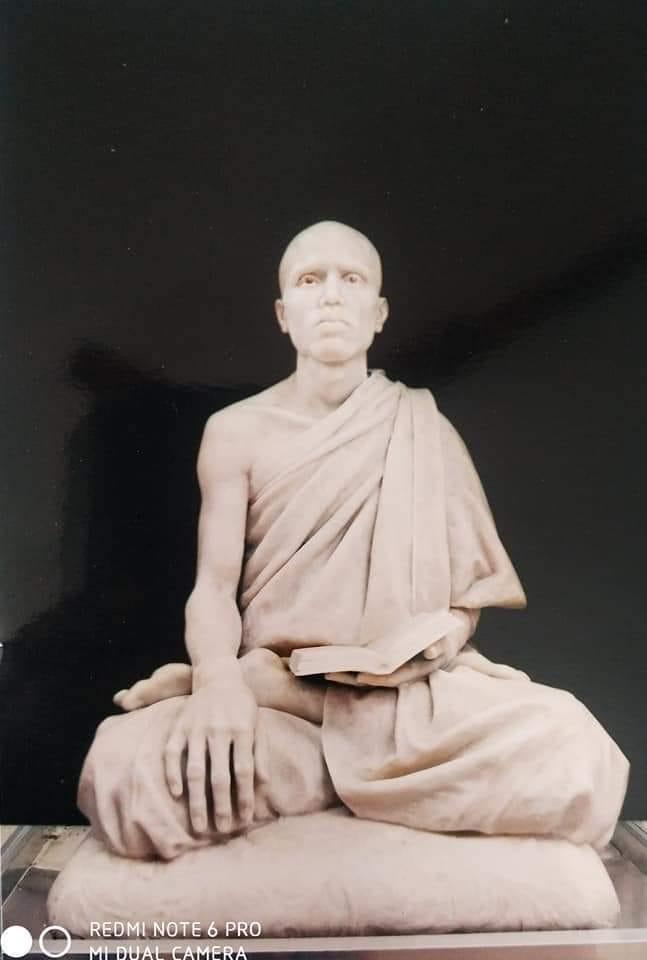

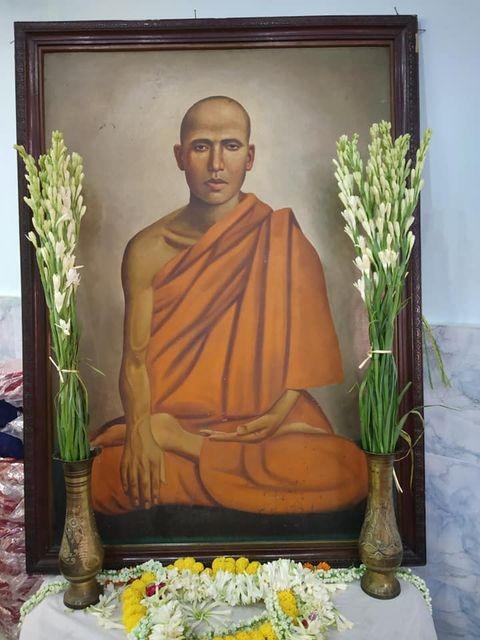

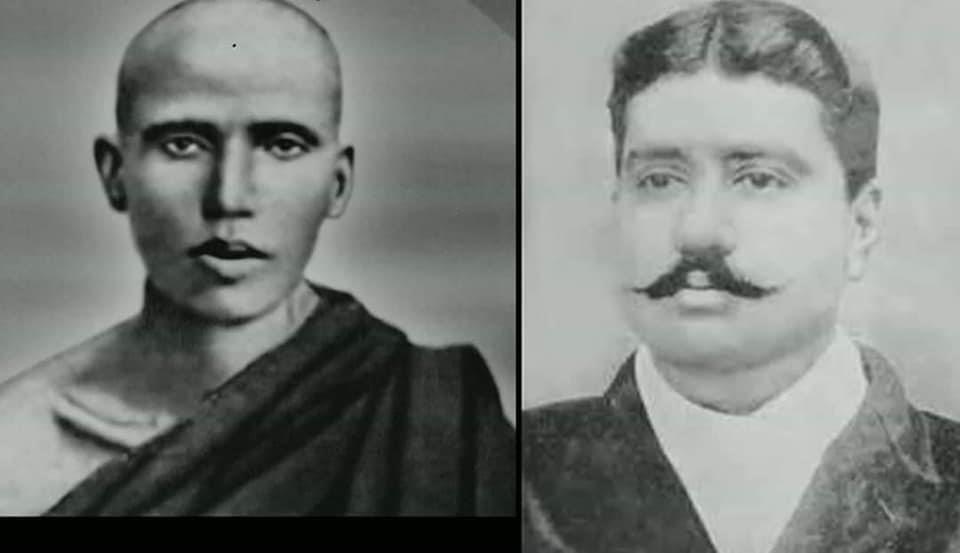

With his soulful gaze and strikingly set brow, the somber countenance of Kṛpāśaraṇa Mahāthērō (22 June 1865–30 April 1927) is instantly recognizable to any Bengali or Bangladeshi nearly a century after his death. The Theravāda Buddhist monk and philanthropist was a key reformer of Indian Buddhism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He pioneered humanitarian and education projects in pre-independence India and Bengal (present-day Bangladesh, and West Bengal in India). Under the watchful eye of the British Raj, and amid a vibrant environment of new intellectual and nationalist ideas, Kṛpāśaraṇa established an impressive number of monasteries, organizations, and educational institutions, most prominently the Bengal Buddhist Association. In recognition of his humanitarian work and tireless support of Buddhism in the Bengal Delta, Bengalis gave him the epithet “Karmayōgī,” referring to him today as “Karmayōgī Kṛpāśaraṇa Mahāthērō” (I will refer to him as simply Kṛpāśaraṇa).

Humble origins and entry into the Buddhist order

Kṛpāśaraṇa was born on 22 June 1865 in Unainpūrā, a Buddhist village in Patiya Subdistrict of Chattogram District in present-day Bangladesh. He was the sixth child to father Ānandamōhan Barua and mother Ārādhanā Barua. The family was poor, and young Kṛpāśaraṇa was never able to attend school. In his commemorative biography, Karmayōgī Kṛpāśaraṇa (1950), scholar Sīlānanda Brahmacārī stated that although Kṛpāśaraṇa suffered from a debilitating state of poverty and deprivation, if he was ever regretful, he never expressed his sorrow to his father.

When Kṛpāśaraṇa was just 10 years old, Ānandamōhan Barua died unexpectedly. His mother, Ārādhanā Barua, became a widow and was unable to care for her children. Young Kṛpāśaraṇa worked as a laborer in a relative’s house to alleviate his mother’s plight. He would earn two takas (the Bengali currency in British India), and gave that money to his mother for family expenses. Ārādhanā was stunned and touched by Kṛpāśaraṇa’s heart and dedication. As time passed, Ārādhanā realized that Kṛpāśaraṇa had a propensity to aid and help others, and that he could be initiated into the Buddhist order as a monk.

Under the mentorship of his preceptor (upajjhāya) Sūdhancandra Mahāsthabīra, Kṛpāśaraṇa was ordained as a novice (sāmaṇera or pabbajjā) on 14 April 1881. As a novice monk, Kṛpāśaraṇa carefully studied the monastic laws and disciplines (vinaya). Thanks to his meticulous learning, Kṛpāśaraṇa established himself as a top student, and was quickly able to attain higher ordination and become a bhikkhu at the age of 20, under the preceptorship of Ācārya Pūrṇācāra Candramōhana Mahāsthabīra (1834–1907), the second Saṅgharāja of Bangladesh.

Kṛpāśaraṇa was eventually given a new monastic name, “Candrajyōti Bhikkhu,” by his teacher. Despite this formal title, his personal name seems to have stuck, and barely anyone used his monastic name with any real consistency or seriousness. The informal name of “Kṛpāśaraṇa Mahāthērō” came to be his most popular, and was the one most recognized by his followers and monastic peers.

Ācārya Pūrṇācāra left a tremendous impact on Kṛpāśaraṇa. After Kṛpāśaraṇa received higher ordination, he traveled to Bodh Gaya with Ācārya Pūrṇācāra. In his book Karmayōgī Kṛpāśaraṇa, Sīlānanda Brahmacārī notes that while at Bodh Gaya, Kṛpāśaraṇa experienced some kind of insight while reflecting on the decline of Buddhism on the Indian subcontinent. At Buddhism’s most sacred yet dilapidated site, he decided to devote his life to reviving Buddhism in India. (Brahmacārī 1950, 14–15)

Aside from his own concern at Buddhism’s disappearance as a living faith, Kṛpāśaraṇa was inspired by the Buddha’s instruction that monks should walk for the welfare of the multitude and for the happiness of many sentient beings (bahujana-hitāya bahujana-sukhāya). This first pilgrimage definitively set Kṛpāśaraṇa on a path that many reformists would follow.

Kolkata and the Bengal Buddhist Association: Kṛpāśaraṇa’s greatest legacy

After Bodh Gaya, Kṛpāśaraṇa returned to Chattogram, settling in the village of Bākkhālī. He continued to meditate on how he could contribute to the Buddhist community by rebuilding its institutions and spreading Buddhism throughout Bengal and India. On 15 June 1886, he arrived in Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) by request and resided at a monastery called Nabīna Bihār, on 72/73 Maṅgalā lē’ina Street.

It was at Nabīna Bihāra that Kṛpāśaraṇa found himself horrified at the laxity and disorganization of the Buddhist communities in Kolkata. He is said to have felt that so lifeless were these groups, they did not seem to care to know their own religion’s teachings. Kṛpāśaraṇa felt that a re-energized and resurgent Bengali society, animated by the urgent calling to protect the ethnic Buddhist communities of Boṅgabhūmi, was the only solution. His first step was to establish Mahānagara Bihāra by renting a place on 21/26 Bho Street. Despite the humble status of his first monastery, Kṛpāśaraṇa’s second and most enduring institution would also be founded in Kolkata. Aware of growing native nationalism under the British Raj, and eager to tie religious identity to national and ethnic belonging, he decided to found a Buddhist organization in the heart of British India.

This Buddhist institution, unlike the lethargic groups that had dismayed him, would actively seek devotees and seekers and bring them together, nurturing in them a cohesive identity as proud students and custodians of the Three Treasures. It was established on the auspicious eve of Prabāranā Pūrṇimā (Āśbinī Pūrṇimā) on 5 October 1892: the Baud’dha Dharmāṅkūra Sabhā (hereon referred to individually as the Bengal Buddhist Association). Contemporary philanthropist and Buddhist scholar Bhikkhu Bodhipala asserts that the Bengal Buddhist Association was one of the pioneering Buddhist groups in British India, and this proud legacy since colonial times has endured up to the present day as Bengal’s representative association. But more was to come.

Kṛpāśaraṇa’s monasteries spread throughout India and Bengal

After successfully establishing the Bengal Buddhist Association and its physical headquarters—a monastery called Baud’dha Dharmāṅkūra Bihāra in Kolkata—Kṛpāśaraṇa’s name spread. This growing esteem prompted a wave of activities by the monk, which mostly consisted of establishing sister institutions (bihāra) in Boṅgabhūmi and beyond. In all these unique and diverse places, Kṛpāśaraṇa always had in mind the needs of those regions’ devotees, mindful that they could not congregate and act without institutional support.

In 1907, Kṛpāśaraṇa purchased a 669-square-meter plot of land in Lucknow so that he could construct a sister institution to Baud’dha Dharmāṅkūra Bihāra, which was named simply Lucknow Bodhisattva Bihāra. In the same year, he established the Shimla Baud’dha Samiti, another branch institution in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh. In 1910, he traveled to Darjeeling to start a new sister institution to Baud’dha Dharmāṅkūra Bihāra. King Bijaẏa Cām̐da Mahatāba, the ruler of Bardhaman, authorized him to found a monastery, although construction would not be completed until 1919. After Darjeeling, Kṛpāśaraṇa traveled to Ranchi, the state capital of Jharkhand. In 1915, he established another new Baud’dha Dharmāṅkūra Bihāra branch in Ranchi with support from the Raj. In 1918, another branch of Baud’dha Dharmāṅkūra Bihāra was established in Shillong, the capital of Meghalaya.

In addition to his activities in northern India and West Bengal, Kṛpāśaraṇa made significant contributions to Unainpūrā, the village where he was born. He renovated and reconstructed the ancient monastery of Unainpūrā Laṅkārāma in 1921. He founded a branch of Dharmāṅkūra Baud’dha Sabhā at the request of village residents. In the same year, he opened a new Dharmāṅkūra Baud’dha Sabhā branch in the Chattogram Hill Tract (CHT) area of Rangamati.

Kṛpāśaraṇa returned to Kolkata in 1922, founding a sister institution of Baud’dha Dharmāṅkūra Sabhā in Jamshedpur, Tatanagar. This was sponsored by a Tata family company in Jamshedpur, based in Tatanagar, which donated to him a 5,620-square-meter site to build a Buddhist monastery and meditation center. Finally, he built a monastery in Shillong two years before his passing in 1925.

Schools, libraries, and journals: education as passion

Kṛpāśaraṇa had been dismayed at the ignorance of Bengali Buddhists, and he placed the blame on their lack of formal education. Prof. Shimul Barua wrote in his book Mānaba Cintanē Bud’dha Cintā-Jāgaraṇē (2021) that the self-educated Kṛpāśaraṇa wanted Buddhists under his care to live and learn differently to him, to enjoy the opportunities he had lacked. As someone who never had the chance to enjoy a formal education, he saw it as the key to securing respectable positions for working people and enabling them to climb above their previous economic station.

Hence, he set about establishing schools and colleges in Boṅgabhūmi. He founded the Kṛpāśaraṇa Free Institution, a non-profit school, in 1913. Despite being located on the grounds of Baud’dha Dharmāṅkūra Bihāra, this school accepted students of all religious backgrounds and provided free education in both Bengali and English. With the assistance of the prominent Buddhist scholar Dr. Benimadhab Barua (1888–1948), Kṛpāśaraṇa supervised this institution and it quickly grew in popularity. In 1916, Kṛpāśaraṇa started an evening school to benefit working people in affiliation with his Bengal Buddhist Association. With the help of academic and journalist W. C. Wordsworth (1878–1950), who was also a former director of Bengal’s Education Ministry, the Bengal Buddhist Association received funding for running both the Kṛpāśaraṇa Free Institution and the Evening School for Working People.

Kṛpāśaraṇa was also friends with Sir Ashutosh Mookerjee (1864–1924), a former vice-chancellor of Kolkata University. Dr. Dharmasen Mahāsthabīra (1928–2020), the late 12th supreme patriarch (Saṅgharāj) of Bangladesh, recognized in Kṛpāśaraṇa Mahāthērō and Sir Ashutosh Mookerjee’s bond a shining example of noble companionship or kalyāṇa-mittatā. (Dharmasen 2021, 436-37) This bond also exerted an influence on secular education in Boṅgabhūmi. Kṛpāśaraṇa convinced Sir Ashutosh that since educational credibility was, for better or for worse, based on university affiliation, rural schools, and colleges needed to tie themselves to the prestigious Kolkata University. This institutional affiliation would encourage pupils from underprivileged schools and colleges to compete for jobs with graduates from more renowned counterparts. Sir Ashutosh, therefore, helped to establish academic ties between Kolkata University and the rural institutions of Caṭṭagrāma.*

Kṛpāśaraṇa also placed a strong emphasis on women’s education. In 1913, he founded the Baud’dha Mahilā Sam’milanī (Buddhist Women Council) organization to enhance the welfare of women. The Baud’dha Mahilā Sam’milanī’s goal was to encourage women to pursue an education and would help by providing scholarships and grants to applicants. While information remains sparse about the female education specialist known only as L.L. Jennie, records suggest that she assisted Kṛpāśaraṇa in launching a scholarship program for women. During the women’s assembly at Baud’dha Dharmāṅkūra Bihāra in 1913, he declared that every woman deserved the same rights as men and that a woman could work outdoors just like a man. To this day, this fellowship remains active, providing financial support to women who are pursuing an education in school, college, and university, as well as vocational training.

Kṛpāśaraṇa recognized the importance of establishing libraries and journals. Prof. Shimul Barua noted that Kṛpāśaraṇa was inspired by the illustrious memory of Nālandā Mahāvihāra (the medieval super-monastery with a famous monastic curriculum). In 1909, he founded Guṇālaṅkāra Library at Baud’dha Dharmāṅkūra Bihāra in Kolkata. With the assistance of the Bengal Buddhist Association, he collected a large number of books, manuscripts, and scriptures for the library. Kṛpāśaraṇa also wanted a platform for local scholars to publish their research. One year earlier in 1908, he had founded Jagaṯjyōti, a monthly Buddhist journal. He picked two renowned scholars, Guṇālaṅkāra Mahāsthabīra and Sāmaṇera Pūrṇānanda Sāmī, to edit the journal. It remains in circulation to this day, shedding light on movements and trends of social and cultural awakening in Bangladesh and India.

Kṛpāśaraṇa’s involvement in education coincided with an increasingly literate society in Boṅgabhūmi and British India, driven by a diverse and sometimes unrelated network of locals (some of them part of the caste elite and educated Europe or America) that chafed under the restrictions of the old ways as well as foreign domination. Understanding the value of education for both men and women, he devoted his life to founding schools and journals as well as supporting local academics and educators. His thoughts about educational welfare were ahead of his time.

A vast and inescapable shadow

Kṛpāśaraṇa passed away in Kolkata on 30 April 1927. One year later, his body was returned to his birthplace, Unainpūrā, as per his final wish. The village was also the site of a grand funeral ceremony, led by Buddhist monks and organized by a large number of devotees.

While he died long before Indian independence and the Partition of Bengal in 1947, let alone the creation of Bangladesh in 1971, it is impossible to separate the flourishing sense of religious and ethno-national identity that defined those periods of modern Bengali—and South Asian—history from the foundations that he built in the early 20th century. Indeed, it might even be fair to call him one of the figures that rode varying waves of nationalism throughout the first quarter of the 20th century. By the time he passed away, India was shuddering under burgeoning ideas of independence and statehood—direct consequences of the activities of influential figures like him. What was even more extraordinary was that, unlike many reformists that came from upper caste or local elite families that had ties to the West, he seems to have remained humble and honest about his impoverished origins for his entire life.

The legacy of Kṛpāśaraṇa continues to enrich and inspire Bengali society, but it is made somewhat more complex by how the region he loved so much was split between India and Bangladesh, two entities he might have struggled to recognize and reconcile. To this day, the Bengal Buddhist Association remains based in Kolkata, but much of what Kṛpāśaraṇa represented and advocated for can be found in the vibrant Buddhist communities of Bangladesh. He spent time in both places. It is perhaps a fruitless intellectual guessing game to think about what he might have done today. What is without doubt is that the shadow he cast is long and vast, touching all of Bengal, regardless of national affiliation or passport. The Bengali communities in Boṅgabhūmi rightly see Kṛpāśaraṇa as having played a critical role in shaping Bengalis’ self-understanding of native heritage during a tumultuous period of political, social, and economic transition that led directly to the decline and eventual fall of the British Raj, ushering in a new and volatile era of national politics for the Indian subcontinent.

It is therefore not helpful to compare him directly to other leading figures of Buddhist reformism, like the more famous Sri Lankan Anagarika Dharmapala (1864–1933), who lived and died at around the same time. Their goals did not necessarily overlap, and the organizations they founded took on divergent identities and trajectories. Most importantly of all, the nations of Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh that were created in the wake of their accomplishments and European colonialism’s formal end in South Asia stand as unique entities of their own.

* These include: Mahamuni Anglo-Pali Institution; Silak Dowing Primary School; Kartala-Belkaine Middle English School; Noapara English High School; Andharmanik High School; Naikaine Purnachar Pali School; Dhamakhali High School; Pancharia Middle English School; Satbaria Girl’s School and Library; Unainpura Primary School; Unainpura Junior High School; Rangunia English High School; M.A. Rahat Ali High School; Sakhpura English School; Rangamati School and Library

References

Brahmacārī, Sīlānanda. 1950. Karmayōgī Kṛpāśaraṇa. Kolkata: Baud’dha Dharmāṅkūra Bihāra.

Bodhipala, Bhikkhu. 2005. Kripasaran: An Epitome of Buddhist Revival. Kolkata: Baud’dha Dharmāṅkūra Sabhā.

Barua, Shimul. 2012. Bānlāra Baud’dha: Itihāsa-Aitihya O Sanskr̥ti. Chattogram: Anōmā Sanskr̥ti Gōsṭī.

Barua, Shimul. 2015. Karmayōgī Kṛpāśaraṇa Mahāthērō Smārakagrantha. Chattogram: Karmayōgī Kṛpāśaraṇa Mahāthērō Sārdhaśatajanmaśatabarṣa Udayāpana Pariṣada.

Barua, Shimul. 2019. Bēṇīmādhaba O Uttarādhikāra. Chattogram: The Kharimāṭi Printers.

Barua, Shimul. 2021. Mānaba Cintanē Bud’dha Cintā-Jāgaraṇē. Chattogram: The Kharimāṭi Printers.

Chowdhury, Sanjoy Barua. 2022. “A Forgotten Buddhist Philanthropist from Boṅgabhūmi: The Life and Works of Kṛpāśaraṇa Mahāthērō (1865–1927)”. In Studio Orientalia Slovaca. Vol. 21.2. 89-115.

Chowdhury, Hemendu Bikash. 1990. Jagaṯjyōti: A Special Edition Commemorating Kṛpāśaraṇa Mahāthērō’s 125th Birthday. Kolkata: Baud’dha Dharmāṅkūra Sabhā.

Mahāsthabīra, Dharmādhār. 2009. “Bānlādēśe Sad’dharma Punarut’thānē Pradhāna Ācāryagana”. In Brahmanda Pratap Barua (ed.). Buddhism in Bengal, 169-80. Kolkata: Barun Kundu.

Mahāsthabīra, Dharmasen. 2009. “Yugasraṣṭā Saṅgharāja Ācāriẏā Pūrṇācāra” In Sathipriya Barua (ed.). Mahājñānī mahājana, 16-19. Chittagong: Gandhara Art Press.

Mahāsthabīra, Dharmasen. 2021. “Unainpūrā Laṅkārāma” In Sajib Barua Diamond, Sanjoy Barua Chowdhury, et al. (eds.). Jyōtirmaẏa, 436–437. Chattogram: Purba Publishing.

See more

Life of Kripasaran Mahashtavir (Dharma Documentaries)

Related features from BDG

The History and Heritage of the Buddhist Diffusion in Boṅgabhūmi

From Vajrayoginī to the Land of Snow: The Legacy of Atīśa Dīpaṃkaraśrījñāna (982–1054)