This article forms part of the “Buddhist Voices from the Land of Rivers” series, which is based on visits by the authors to Buddhist sites in Bangladesh and their meetings with leaders and activists from the Buddhist community.

When Samaneri Gautami publicly announced her intention to take novice or samaneri ordination, there were no objections from Bangladeshi monks; in fact they were very supportive. She and four other women from Bangladesh and two from Calcutta were ordained together in India. Subsequently, 18 other women, inspired by their example, also took novice ordination in India. “I was given the sangha name Gautami to represent my work leading the bhikkhuni order and the female community in Bangladesh, like the Buddha’s stepmother Pajapati Gautami,” says Samaneri Gautami.

Returning home, she met the Sangharaja or Supreme Patriarch of Bangladesh, the deputy Sangharaja, and several senior monks, and received many invitations to continue to teach the Dhamma and guide meditation retreats, which she had already been doing prior to taking ordination. She was overjoyed, as it would help her to serve as an inspiration for other women. “Women were beginning to emerge from the darkness for the first time, understanding that touching monastic robes was not a sin and [that] even women could be ordained,” says Samaneri Gautami. “I thought of having women ordained in Bangladesh.”

However, this determination to revive the bhikkhuni (fully ordained female monastic) order in her home country would lead to a series of run-ins with senior sangha members in Bangladesh. Samaneri Gautami made plans to hold a female novitiate ordination ceremony in Bangladesh in January 2013, and invited monks from Bangladesh and India. They included Venerable Dr. Bharasambodhi, a Bangladeshi monk living in India, whom she knew from teaching the Dhamma and meditation. The invitation was accepted by the deputy Sangharaja of Bangladesh, Venerable Praggabangsa Mahathera, and many other senior monks. Her initial target was to ordain 20 nuns, but the number soon increased due to interest raised by posters announcing the initiative. Despite an initial warm reception, however, the path to Samaneri Gautami’s vision was to prove a rocky one.

“Just one week before the ceremony, many senior monks secretly held a meeting and decided to pressure us to cancel the ceremony,” says Samaneri Gautami, adding that prior to this meeting, these monks had donated boxes of robes. “After the meeting I was told female ordination could not be held in a Muslim country. I told them that all this time, although I was not given any security, I was safe and never threatened by the Muslim community.”

The senior monks continued to oppose the initiative although by this time it was too late to cancel the program, so they instructed Samaneri Gautami not to use monastic robes, which in the Theravada tradition are saffron or orange, but to use either white or pink robes instead. Finally Venerable Sasanapriya, then secretary of the Bangladesh Sangha Council, arranged for her to meet the director of the Sangha Council, who reiterated the old but unsubstantiated caveat of a woman’s contact with monastic robes being a sin. As he was a senior monk, Samaneri Gautami could not object. He also instructed her to use only white robes for the ceremony.

“I reminded him that I was officially and properly ordained by the sangha according to the Vinaya. I suggested that as Venerable Dr. Bharasambodhi was coming to Bangladesh from India, this issue could be discussed with him in detail to ensure the ordination ceremony was held in accordance with Vinaya rules. After that I would consent to their instructions,” she says. Unfortunately, this suggested meeting did not take place.

“We continued as planned and I re-invited the monks to attend the ceremony, explaining there were no other alternatives or enough time to reschedule,” Samaneri Gautami continues. “I agreed to implement any later instructions I received after the ceremony.” Despite the growing public interest in the ordination, however, most of the senior monks still did not attend, but continued to oppose the ceremony. Moreover, during Venerable Dr. Bharasambodhi’s visit, none of the senior monks requested a meeting to discuss female monastic ordination. “As soon as he left for India, the senior monks came to my residence and officially ordered me to disrobe within seven days,” she states.

“They brought some leaflets stating that women who touch robes are committing a sin. I asked them to enumerate any mistakes I had made.” Their reply, she says, was that bhikkhuni ordination was impossible as Bangladesh was a Muslim country, although she reminded them that so far no Muslims had harmed her; it was only the senior monks offering opposition. “Then I asked, ‘What wrong have I committed? Is it because I am female?’ When I said this, they didn’t answer,” she recalls.

“The Buddha even accepted the invitation for alms from Ambapali, who was a courtesan. . . . I was very sad after having done so much for the society,” she said. “I have taught meditation in several places where hundreds of participants attended. I was even invited by the deputy Sangharaja on his birthday to teach meditation. So it was really sad to be treated in such a manner by senior monks.”

Sramoni Sangha Facebook

Samaneri Gautami has since determined to make it her life’s goal “to strive so that the next generation of women doesn’t face such difficulties. I want at least their desire for an ordained life to be one of free choice and beauty.”

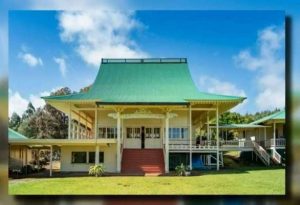

After arriving at her residence, we noticed that besides the support of a few other novice nuns and four women who had undertaken to observe the Eight Precepts, Samaneri Gautami also received strong support from the lay community. We were keen to hear her future plans for the women living with her and for securing a formal nunnery or monastery, which would provide more security and recognition.

“Those who received the ordination will remain, and some are planning to be ordained in the future. I am aware of this problem,” she said. “There are some devotees who wish to donate a place for building a nunnery. I hope I can provide more space for people to practice meditation.”

In June this year, Jnan Nanda and Samaneri Gautami met again in Indonesia at the 14th Sakyadhita International Conference.* Looking relaxed and happy, she shared many updates on the development of the bhikkhuni order in Bangladesh. Despite continued pressure from senior monks, Gautami’s influence within and outside the lay Buddhist community in Bangladesh continues to grow. Among lay Buddhists she is a Buddhist nun who receives the respect she deserves, while in non-Buddhist communities she is seen as an activist for women’s rights, appreciated and supported by other activists and human rights organizations. There has as yet been no official recognition from the Bangladesh Sangha Council for either full or novice female ordination, but many monks have provided help and support in various ways, which Samaneri Gautami values highly.

Currently, the number of samaneris residing with Gautami—including newly ordained novices—numbers eight (some of the others having disrobed), and due to her efforts to provide a better religious environment for Buddhist women in the country there are now even “requests from non-Buddhist women, including university students, for ordination.” So far she has refused, afraid that she will face more trouble if she consents.

Ven. Prof. Bhikkhuni Dhammananda from Thailand was one of several nuns that Samaneri Gautami met at the conference. Ven. Prof. Dhammananda has herself faced difficulties in Thailand after her ordination. Having learned to speak Bengali while studying in Calcutta, she was so happy to meet and speak Bengali with the three samaneris from Bangladesh that she invited them to Thailand for a one-month training retreat under her supervision, to which the nuns readily agreed.

The nuns hope to travel to Thailand in November this year. Samaneri Gautami told Jnan that Ven. Dhammananda is also planning to arrange for higher ordination for the visiting nuns in December, after their retreat. If everything goes as arranged, this will be another successful milestone for Samaneri Gautami, for her junior colleagues, and for the bhikkhuni order as a whole.

We feel strongly that Samaneri Gautami’s unique and passionate voice deserves to be heard because her actions can motivate Buddhist women in Bangladesh, enabling them to play important roles in uplifting the local Buddhist community.

John Cannon is the former content editor and Jnan Nanda, currently a PhD candidate at the University of Hong Kong, is the former news and media analyst of Buddhistdoor Global.

See more

The Journey of Women Going Forth into the Bhikkhuni Order in Bangladesh: An Interview with Samaneri Gautami, Part 1 (Buddhistdoor Global)

“Buddhist Voices from the Land of Rivers”: Let Hope Rise from the Ashes (Buddhistdoor Global)

“Buddhist Voices from the Land of Rivers”: Looking from the Inside Out (Buddhistdoor Global)

“Buddhist Voices from the Land of Rivers”: Moanoghar, Beacon of Hope (Buddhistdoor Global)

“Buddhist Voices from the Land of Rivers”: In Conversation with Venerable Buddhadatta (Buddhistdoor Global)

“Buddhist Voices from the Land of Rivers”: Villagers Observing “Uposatha” in Rangamati (Buddhistdoor Global)