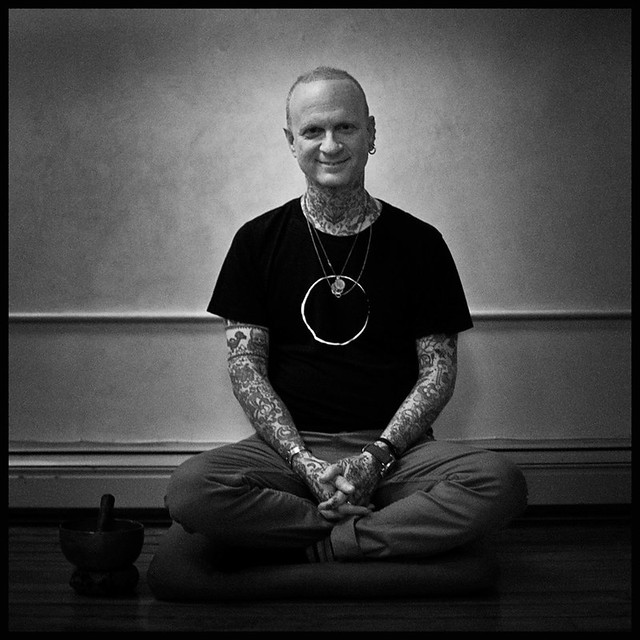

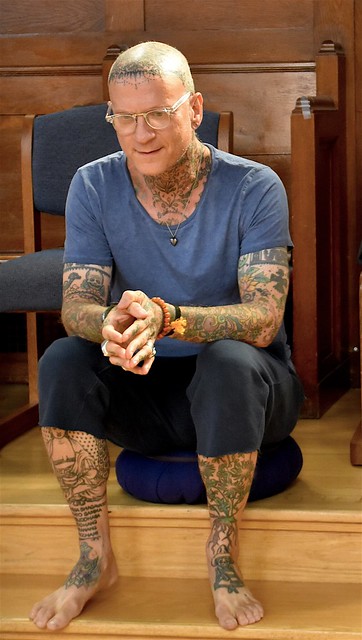

What kind of path in life leads one to become a Dharma teacher? Josh Korda’s journey is probably not what one might expect. He hasn’t taken up monastic training and robes, nor does he speak in the hushed tones of the post-hippy boomer meditator. Instead, dominating the young-looking smile and kind eyes one might expect from a person steeped in years of meditation and the study of Buddhist sutras, and the clothes of a fashionable urbanite, are a head and arms heavily decorated with tattoos. As it turns out, tattoos are not uncommon at the Against the Stream Buddhist Meditation Society, where Josh Korda is an authorized teacher under the tutelage of the also-very-tattooed founder, Noah Levine.

Today, Korda is the guiding teacher of Dharma Punx NYC and a visiting teacher with the Zen Center for Contemplative Care. He is also the author of the newly released book, Unsubscribe: Opt out of Delusion, Tune into Truth (Wisdom 2017), in which he chronicles his journey from drug and alcohol addict to teacher of Buddhism. I recently spoke with Josh Korda about his life, history of difficulties, and his new found role as a teacher of meditation with a nuanced understanding of both the Dharma and Western psychology.

Buddhistdoor Global: You lay out your history beautifully in your book, but could you give us a short summary—Josh Korda in a nutshell?

Josh Korda: Well, I’m a lifelong New Yorker/Brooklynite, son of a first-generation American artist (father) and writer (mother). Due to early traumas involving my father’s alcoholism, I too became a low-bottom alcoholic and drug addict. Fortunately, I managed to get clean over 22 years ago, largely through 12-step support and Buddhist practice. During my drinking years, and for a period after, I worked in advertising while practicing in various sanghas. In 2002, I met Noah and became a devotee of what I’d call the Dharma Punx approach to the Dharma. In 2005 I became the guiding teacher of Dharma Punx NYC, a role I’ve sustained ever since.

BDG: My sense is that the life you’ve lived has made it a lot easier for many people to relate to you as a human, but how do you move from the “we’re both suffering humans” connection to the teacher-student relationship?

JK: Ha! I don’t move out of the “we’re both suffering humans” connection. That’s always a part of my spiritual counseling; as I was a sponsor for many years in recovery programs, I always connect and offer support through disclosing my own experiences. I believe deeply in personal disclosure, a foundation I’ve used throughout my teaching and articles for various Buddhist publications.

BDG: A lot of deeply personal revelations about your life come out in your book. Was that difficult for you, sharing your own battles with addiction, the loss of a good friend, feeling the sting of your wife calling you a prima donna?

JK: Not as much as you’d expect! After years of disclosing my most embarrassing, shameful, and painful experiences to rooms filled with strangers—that’s the deal if you want to recover from addiction, which itself is an attempt to repress or deny painful emotions and experience—taking it one step further and laying it on the line in a book came naturally. I’m much happier being transparent. As many psychologists have noted over the years, keeping experiences hidden leads to stress and anxiety.

BDG: Two fascinating aspects of this book are your use of modern psychological research to illuminate Buddhist truths, and your almost exclusive use of Theravada/Pali material. Starting with the second one first, one of the tropes of Mahayana is that it is the vehicle best suited for addressing the full breadth of human emotions and experience. Inside this claim is the sometimes subtle, sometimes not, critique of “Hinayana,” by which is often meant Theravada, Buddhism as limited in scope: fine for a few but not really the masses. Surely you’ve encountered this along with some of the amazing Zen and Vajrayana teachers out there. What keeps you working with Pali texts?

JK: Because Theravada was originally associated with the renunciate path, i.e. nuns and monks living in monasteries and strictly following 227 precepts, other branches of Buddhism believed it was emotionally stifling. Of course, this is a vastly distorted view of the Pali canon, which contains countless suttas in which the Buddha extols the virtues of knowing and expressing emotions. For example, the second and third foundations of mindfulness emphasize affect awareness, while kalyana-mitta, or true friendship, where one shares all of one’s secrets and experiences with friends, is presented as the whole of the path, the prerequisite . . . not that meditation is more important!

BDG: Using contemporary psychology is sometimes discussed as being a double-edged sword: on the one hand it gets people engaged and shows the relevance of the Buddha’s teachings. On the other hand, it can lead people to reduce Buddhism to a therapy technique or, when psychological claims are thrown into question, people might think that Buddhism is dubious as well.

JK: I grew up in an apartment where the bookshelves were lined with books by Freud, Jung, Erickson, Rank, and Klein (my mother’s collection) along with books on Buddhism (my father’s). As a teen, when I read The Three Pillars of Zen I never saw much of a difference between it and the other psychology books I read! To this day I view the Buddha as a psychologist, not a religious figure. Furthermore, presenting the Buddha—and the Dharma—in a mystical or religious frame leaves it just as vulnerable to other charges, namely it being inappropriate for therapeutic or clinical modalities, it being unfounded, dubious religious dogma, and so forth. I’d rather Buddhism receive the recognition it deserves as the first cohesive and useful psychology, geared towards ending unnecessary suffering and presenting practices that cultivate peace of mind.

BDG: That leads us into my next question. You make it clear that you’re not a “mindfulness teacher” in the sense of the movement of people teaching a limited technique focused on helping alleviate stress or physical pain. Do you think there is an appropriate place for all of this, perhaps even in your own path and teachings? Or are there lines that you find pretty clear that you won’t cross?

JK: Mindfulness in its current form, via John Kabat-Zinn’s adaption of the Four Foundations of Meditation [Satipatthana Sutta], in which he stripped the sutta of its Pali terms and its language, but kept the tools intact, is a fine set of psychological tools for both dyadic work (with a therapist) and self-soothing and stress reduction. But that’s not enough to achieve lasting change. Human beings are social beings and especially vulnerable to emotion contagion; if we work long, stressful hours, isolate ourselves from community and the emotion co-regulation provided by friends, no amount of meditation and mindfulness will suffice. Hence, the other factors of the Eightfold Path outside of meditation: especially the factors of right livelihood, action, speech, and intention. At the risk of sounding repetitious, the Buddha said friendship was the foundation of the path, not mindfulness or meditation. The Buddha was certainly correct, as clinical psychologists and psychiatrists such as Allan Schore, Peter Fonagy, John Bowlby, Mary Ainsworth, Mary Main, and many others have amply demonstrated.

BDG: Excellent. Coming back to the book: where do you hope this book goes? Who do you think most needs to read it?

JK: I wouldn’t presume to answer that. I just hope that those who spend their precious time with it find something of value. Beyond that it’s all gravy, as they say.

BDG: And lastly, where next? What project do you hope to be working on in the years to come?

JK: Well, I’d love to write another on a subject I’ve been working on recently, namely how to feel secure in a world that’s unreliable to say the least. Or, as I put it in a talk right after Trump was elected, “how to stay sane in a sh*t show.”

See more

Against the Stream Buddhist Meditation Society

Dharma Punx NYC

Why I Come Clean to Students About My Insomnia, Anxiety, and Sobriety (Tricycle)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

From Chamonix to Chenrezig and Thangkas to Mountain Landscapes – The Story of Neljorma Tendron

An Olive Branch: Reaching Out to Those Affected by Abuse in Buddhist Sanghas

Exploring Engaged Buddhism with Professor Christopher Queen