This article originally appeared in Buddhistdoor en Español.

Few 20th century thinkers have been so influential in Mexico’s social and cultural life as José Vasconcelos (1882–1959), a philosopher and poet, erudite politician, and educational ideologue. From Oaxaca, he was also known as the “Teacher of the Americas” and is renowned for his contributions to building a widespread public educational project, with support from the Secretariat of Public Education (SEP). Vasconcelos was instrumental in founding this institution in 1921, from which he promoted education with the hope of it becoming universal in a Mexico struggling to define the boundaries of its national identity after a chaotic revolutionary process. Among many other achievements, Vasconcelos is also known for being the rector (1920–21) of the National University of Mexico (today the National Autonomous University of Mexico [UNAM]), which he endowed with his iconic and famous motto: “Through my race, the spirit will speak.” The phrase summarizes his polemic theory that the Latin-American mixed “race” would end up becoming the apogee of world civilization.

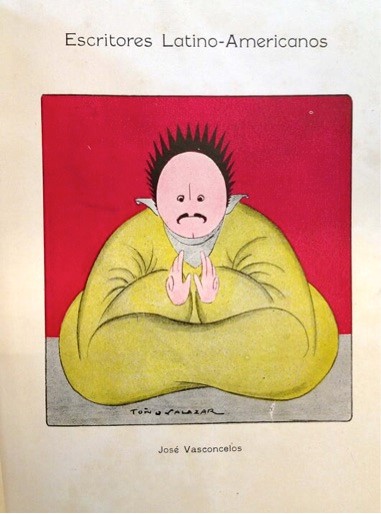

Conversely, Vasconcelos’ fascination with Asian cultures—particularly Buddhism—is one of his facets that is still relatively unknown today. This would not seem to be the case in his day, during which his contemporaries were familiar with his love of the East, especially for India. The testimonies of other authors mentioned it, as well as some visual sources, including a notable caricature in the magazine La Falange in 1922. Illustrator Toño Salazar represented him as a seated buddha dressed in an enormous yellow tunic, with his characteristic prominent ears and spiky hair. Six years later, in 1928, Diego Rivera would satirize Vasconcelos in his mural Los Sabios (The Wise Men). Salazar painted him with his back to viewers, sitting on a white elephant, an unmistakable symbol of his passion for India. The mural is on the same building that houses the SEP, which Vasconcelos founded and built.

From revista.reflexionesmarginales.com

Given that Buddhist ideas and symbols were decisive to his thought and person, both personally and ideologically, it is worth considering his role as part of an early chapter in Buddhism’s entry into modern-day Mexico.

Vasconcelos was not alone in this reception and interpretation process. Before him, writer Amado Nervo (1870–1919), primarily influenced by theosophical versions of Buddhist sources, had composed verses and stories in which he intermixed Buddhist ideas with Christian mysticism and notions of Hinduism. In parallel, poet José Juan Tablada (1871–1945) would introduce haiku and some concepts from Zen Buddhism into Mexican literature after a trip to Japan in 1900. However, Vasconcelos’ approach to Buddhism would be very different from that of his contemporaries. Unlike Tablada, Vasconcelos never visited any country with a Buddhist population and probably never saw a Buddhist monk firsthand. In contrast to Nervo, Vasconcelos would reject the influence of theosophy, which he accused of “in general, not being careful with the authenticity of its quotes, or following any methodology.” (1961 [1937], 127)

Vasconcelos particularly abhorred the works of its main authority, Madame Blavatsky (1831–91), whose writings and interpretations he found replete with “charlatanism and ignorance.” (1938 [1920], 85 No. 1) His exposure to Buddhism came from two main sources: art and texts. They must have been fertile seeds for him, leading him to eventually produce studies on Buddhist thought and religion and to create Buddhist images as part of the symbolic imagery for his institutional educational project.

His direct contact with Buddhist art—and with the visual diversity of different Buddhist schools—would seem to date back to his period of exile in the United States and Europe from 1915–20. During this time, Vasconcelos would visit New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and Paris’s Louvre and Guimet Museums, all of them with extraordinary Asian art collections, where he would have gazed upon Buddhist pieces from sites as diverse as India, Southeast Asia, Gandhāra, China, Japan, and Tibet, perhaps shaping a vision of the complexity and multiplicity of these traditions. He mentions the Guimet in his memoires: “The passion for all that is Hindustani kept us in this . . . site.” (1998 [1936], 41) It is nonetheless striking that in his writings about Buddhist art, particularly the section “Hindu art” in Aesthetics (1936), Vasconcelos omits any reference to the differences between Buddhist schools, as if he could not or did not want to recognize the differences.

Vasconcelos’ early readings of Buddhist texts seem to have been prior to this time, perhaps before or round 1908, the year that the Youth Athenaeum was founded. This discussion and reflection group was made up of young intellectuals of the day, including Antonio Caso, Pedro Henríquez Ureña, and Alfonso Reyes. Vasconcelos himself recounted that he brought “for the first time to the meeting, a double volume of the dialogues of Yajnavalki [sic] and Buddha’s sermons in the English edition by Max Müller, recent at that time.” (2014 [1935], 352) Although Vasconcelos did not name the aforementioned Buddhist work, everything would seem to point to it being the famous Dhammapada, a Pali work that Müller translated into English in 1881. However, it would also be during his exile when he must have devoted himself more seriously and systematically to the reading and study of Indian works and academic pieces by European and American orientalists in the libraries of different cities, especially those in New York.

The result of his work would be one of his most important writings, Estudios indostánicos (Hindustani Studies, 1920), in his own words: “a sort of manual for the study of Hindustani thought.” (1938 [1920], 9) In this book, touching on a range of philosophical and religious currents in India, Vasconcelos devotes a long section to Buddhism, one of the first important Latin American contributions—and definitely the first Mexican one—to the informed study of Buddhist thought. Despite countless imprecisions, generalizations, oversights, and methodological mistakes, Vasconcelos’ book represents an initial effort to study and understand Buddhism from its sources and via erudite reflections made by renowned 19th and early 20th century orientalists. His main source would seem to have been Paul Carus’ The Gospel of Buddha from 1894. Vasconcelos also consulted other Buddhist, Sanskrit, and Pali works for his book in translations directly to English and French, somewhat unusual in a Latin American setting dominated by theosophical versions.

Although Vasconcelos expressed interest in The Lotus Sutra (in Burnouf’s translation, 1852) and the Lalitavistara Sūtra (the version by Foucaux, 1892) as a basis for the account he wrote of the Buddha’s life, Vasconcelos focused his attention on works by non-Mahāyāna schools, including the Buddhacarita by Aśvaghoṣa. In studying the doctrines, he completely omitted Mahāyāna sources, favoring exclusively several titles from the Pali Canon (in the English translations of the Pali Text Society and the Sacred Books of the East series), especially turning to the Theragāthā and Therīgāthā (Therita-Gata [sic]), Jātakas, Vinaya, and Milindapañha. He thus created—without planning to— the idea of a Buddhist corpus whose impact on readers has yet to be studied. In parallel and via this work, Vasconcelos launched and established the foundations for Buddhist and Indology studies (“Hindustani” as he would have said) in Mexico, fields of academic study for which there would be a vacuum of important works in this country for several decades afterward.

The same year, 1920, in which Hindustani Studies was published, Vasconcelos’ exile ended and he returned to Mexico, working as the rector of the National University. One year later he founded the SEP, an institution from which he would conduct radical and sweeping reforms of education in Mexico, including the federalization of public education, the creation of public libraries, the universalization of education with rural teachers, and the mass publication at affordable costs of philosophical and literary classics. Vasconcelos’ goal of “creating the characters for a native Hispanic-American culture” (2011 [1921], 221), and his ideal of an educated and enlightened Latin-American people were based on what he considered as the civilizing pillars by antonomasia: Mesoamerica, Greece, Spain, and India.

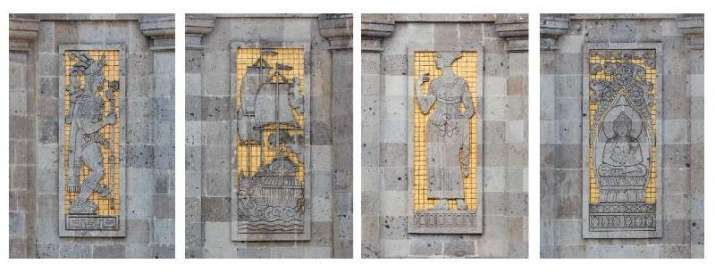

His vision was artistically captured in the Fiesta Courtyard of the SEP building in Mexico City’s Historic Center. Vasconcelos instructed Puebla artist Manuel Centurión (1883–1952) to create four bas-reliefs representing these four core areas. They depict the civilizing hero of Mesoamerica with the legend “MEXICO / QVETZALCOATL;” a woman representing Greek culture bearing the legend “PLATO / GREECE;” and Spanish roots are represented by a caravel reading “LAS CASAS / SPAIN.” Finally, Eastern influence is embodied by the Buddha, with the legend “BVDA / INDIA.” The Buddha is seated on a lotus, with his hands in the dhyāna mudrā, surrounded by a halo and aura. Above him are decorative plants and clouds. The illustration is a hybrid and seems to be inspired by several sources—possibly of Japanese, Chinese, Thai, and Tibetan origins.

It is highly significant that Vasconcelos included the Buddha along with references to Quetzalcoatl, Plato, and Bartolomé de las Casas, thus acknowledging his role as an educator and highlighting his teachings as a fertile source that could nourish his ideal of the Latin American civilization. In his own words, he included these four references “as a suggestion that in this land with this Indo-Iberian lineage, the East and West, the North and South had to all come together, not to clash and destroy each other, but to combine and meld together into a new loving and synthetic culture.” (2011 [1921], 221)

The figure of the Buddha as part of this same ideal is also captured in a mural painted by Jalisco-native Roberto Montenegro between 1922 and 1923, which is in Vasconcelos’ office. It is titled Wisdom, Hindustani Studies, Religious Ideologies and depicts a Buddha on its left side, clearly influenced by Japanese representations, sitting on a lotus that, in turn, rests on a white stone elephant. Unlike the Buddha in the courtyard, whose possible viewers were everyone entering the building, the Buddha in Vasconcelos’ office would be reserved only for him and his visitors.

In the first three decades of the 20th century, Vasconcelos showed a great fascination for Buddhism, recognizing in the Buddha a wise man who inspired him, both personally and within the scope of his educational project. His interest in this tradition was so great that even though he was unable to abandon his Christian identity, he sought a way to reconcile both religions. In his book El Monismo Estético (Aesthetic Monism 1919) and, particularly, in Hindustani Studies (1920), he formulated the idea that Christ was none other than Maitreya, the future buddha that Śākyamuni had announced. This let him fully embrace his mystical vision of Christianity, taking only those features from Buddhism that he considered compatible with his vision of human improvement, outside of all the ritual, devotional, and contemplative practices.

Despite having a selective approach toward Buddhist traditions due to the circumstances of the era, Vasconcelos can be recognized as one of the most important characters for the early introduction of Buddhism in Mexico, a model with a controversial personality and controversial ideas, both in his day and now, but one who undeniably represents a prominent person in the history of Buddhism in Mexico.

This article is part of a study underway on the history of Buddhism in Mexico.

Works by Vasconcelos cited:

1938 [1920], Estudios indostánicos, Mexico, Ediciones Botas.

1961 [1936], Historia del pensamiento filosófico, in Obras completas de José Vasconcelos, Mexico, Libreros Mexicanos Unidos.

1998 [1936], La tormenta, Mexico, Trillas.

2011, [1921], La creación de la Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico, INEHRM and SEP.

2014 [1935], Ulises criollo, Mexico, Porrua.

Roberto E. García is a Sanskrit and Pali translator and a scholar of the narrative traditions of Indian Buddhism. Today he is a professor-researcher of Buddhist studies at the Center for Asian and African Studies (CEAA) at Mexico College, where he conducts research on the lineage of royal (regia) authority in literature on Indian Buddhism, and on the history of Buddhism in Mexico. García has published several academic essays on Buddhist literature and culture. Meriting mention among his publications is the book Jātakas, Antes del Buddha. Relatos budistas de la India, a direct translation from Pali of stories of the Buddha’s past lives. From 2015–17, he was a researcher and translator at the Buddhist Translators Workbench, a Sanskrit lexicographic project of the Mangalam Research Center for Buddhist Languages in Berkeley, California.

See more

Panorama general de la revista “La Falange” (1922-1923) (Reflexiones Marginales)

Los sabios (Goverment of Mexico)

Oficina y salones del secretario (Goverment of Mexico)

Roberto E García (Academia.edu)

Imagining the Buddha in the Art of Ancient India (YouTube)

The past lives of the Buddha: an introduction to the genre of the jātakas (YouTube)