Japanese Buddhist poems are known for their haunting beauty, conjuring up feelings of melancholy and solitude. They are also interpreted to reflect the aesthetic principles of wabi-sabi. In some sense wabi designates the emotive response to the artistic representation of simplicity and solitude. Also, known are the Edo period (1603–1868) of the “floating world,” ukiyo-e. The term ukiyo (“floating world”) is a homonym of “gloomy world” (ukiyo). The emotions expressed in Japanese art, including poetry, literature, calligraphy, performative arts, paintings, and so on, cover a wide spectrum. In this essay, I would like to focus on expressions of melancholy in Buddhist poetry and explore what their message may be.

The most well-known Japanese poet with Buddhist leanings is probably the famous haiku poet Matsuo Bashō (1644–94). Haiku are poems in three lines featuring five, seven, and five syllables, respectively. Many people have heard the following poem by him:

furuiki ya the old pond

Kawazu tobikomu a frog leaps in

Mizu no oto the sound of the water

(Davis 2019, 731)

This poem uses nature symbolism to express how one moment, the moment of awakening, can encompass the whole cosmos. In other words, this poem combines imagery of naturalness and simplicity to articulate and illustrate the Buddhist theory of momentariness, claiming that “three worlds are in one instant” (Chin: chana sanshi) and the “three thousand worlds are in one single thought” (Chin: yinian sanqian). These phrases are often interpreted to articulate the mystical experience.

But there is another dimension to these kinds of expressions—the reality of impermanence. In Heian Japan (794–1185), the melancholy caused by the awareness and experience of transience was a pervasive theme. The Tale of Heike,* which reports events from the end of the Heian period, tells the story of Giō, who is released from her position as a dancer at the court of Taira no Kiyomori (1118–81) when the younger Hotoke shows up. Giō summarizes her feelings in a tanka. Tankas constitute poems in five lines featuring five, seven, five, seven, and seven syllables, respectively.

moeizuru mo since both are grasses

karuru mo onaji of the field, how may either

nobe no kusa be spared by autumn

izure ka aki ni the young shoot blossoming forth

awade hatsu beki and the herb fading from the view

(McCullough 1990, 34)

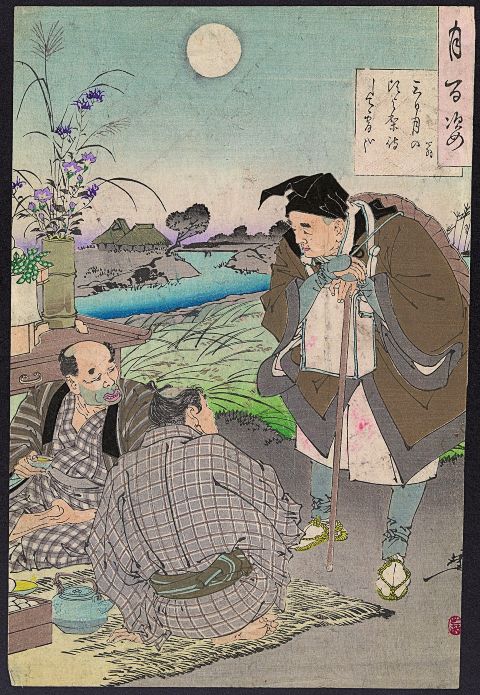

The same sense of transience is also reflected in the poetry of famous Buddhist monks in Japan. Saigyō Hōshi (1118–90), an itinerant poet-priest of the late Heian period, explicates the melancholic character inherent in the experience of transience.

kokoro naki even a body without a heart

mi ni mo aware wa can still know

shirarekeri what melancholy is

shigi tatsu sawa no when a snipe flies out on a marsh

aki no yūgure in autumn twilight

(Raud 2019, 142)

The mind of momentariness captures the continuous flow of reality in one snapshot. In this moment, when a bird flies out onto the marsh, the cosmos and the buddhas manifest themselves. Cutting off the “before and after,” residing neither in nostalgia for the past nor in the hope for a better future, and relinquishing the desire for permanence all express the “wisdom” (Skt: prajñā) of the Buddha. Yet, according to these Buddhist poets, we detect a feeling usually not associated with awakening in this experience of momentariness: melancholy.

The Edo period Buddhist Zen master Ryōkan Taigu (1758–1831) goes one step further. He not only acknowledges the reality of impermanence and the experience of melancholy, Ryōkan even mourns his old age and failing health, the insomnia that goes along with it, and the struggle of light and heat against the cold and darkness:

老朽夢易覚 old and withered I wake easily from my dreams

覚来在空堂 and find myself in an empty hall

堂上一盞燈 where there is but one candle

挑尽冬夜長 struggling to persist in the long winter nights

(Imoto 2009, 118)

The question that these kinds of poems raise is whether these poets, especially Ryōkan, failed to attain awakening and to defeat the four characteristics of suffering, birth, old age, sickness, and death? Do their poems indicate defeat, attainment, or rebellion? Ryōkan is usually considered one of the “crazy monks” and as such joins the ranks of Jigong (1130–1207), Wǒnhyo (617–86), and Ikkyū (1394–1481). These monks gained a reputation for undermining the precepts in the name of the “skillful means” (Skt: upāya) and “compassion” (Skt: karuna). Did they also subvert Buddhist orthodoxy?

I don’t think so. I believe that these poems are reminders of the old Mahāyāna insight that saṃsāra and nirvāṇa are not separate from one another. As the Zen adage states: “This mind is the Buddha”** (T 2005.48.296c28). Dōgen identifies “buddha-nature” as “impermanent”*** (DZZ 1:21). Buddha cannot be found but in the transient moments of our life. Every moment is fully contained in itself. Dōgen calls this a “Dharma-position” (Jap: hōi) that expresses the “dynamic totality” (Jap: zenki) of all buddhas, ancestors, and bodhisattvas. This complete immersion in the moment that reveals the activity of all buddhas past and future is what these poems point us to. This Dharma-position, which reveals the workings of the cosmos in all of its simplicity and melancholy, is beautifully illustrated by Dōgen’s description of the passing of the seasons.

haru wa hana in spring, flowers

natsu hototogisu in summer, cuckoos

aki wa tsuki in autumn, the moon

fuyu yuki saete in winter, snow

suzushi karikeri vivid and cold

(Dōgen, Sanshōdōeishū 6)

* Samurai and Monks: Lessons in Impermanence (Buddhistdoor Global)

** “This Mind is the Buddha”* — Being Religious (in Japan) (Buddhistdoor Global)

*** Does a Philosopher Have Buddha-nature? (Buddhistdoor Global)

References

Imoto, Nōichi. 2009. Ryōkan 2. Tokyo: Kōdansha.

Davis, Brett. 2019. “Expressing Experience: Language in Ueda Shizuteru’s Philosophy of Zen,” in The Dao Companion to Japanese Buddhist Philosophy, ed.: Gereon Kopf, 713–38. Dordrecht: Springer Nature.

Dōgen zenji zenshū (Complete Works of Zen Master Dōgen). 2 volumes. Ed. Dōshū Ōkubo. 1969–70. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō. [Abbr. DZZ]

McCullough, Helen Craig (trans.). 1990. Tale of Heike. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Raud, Rein. 2019. “Japanese Thought and the Japanese Cultural System,” in The Dao Companion to Japanese Buddhist Philosophy, ed.: Gereon Kopf, 135–54. Dordrecht: Springer Nature.

Takakusu, Junjirō and Kaigyoku Watanabe, eds. 1961. Taishō Taizōkyō (The Taishō Edition of the Buddhist Canon). Tokyo: Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō Kankōkai. [Abbr. T]