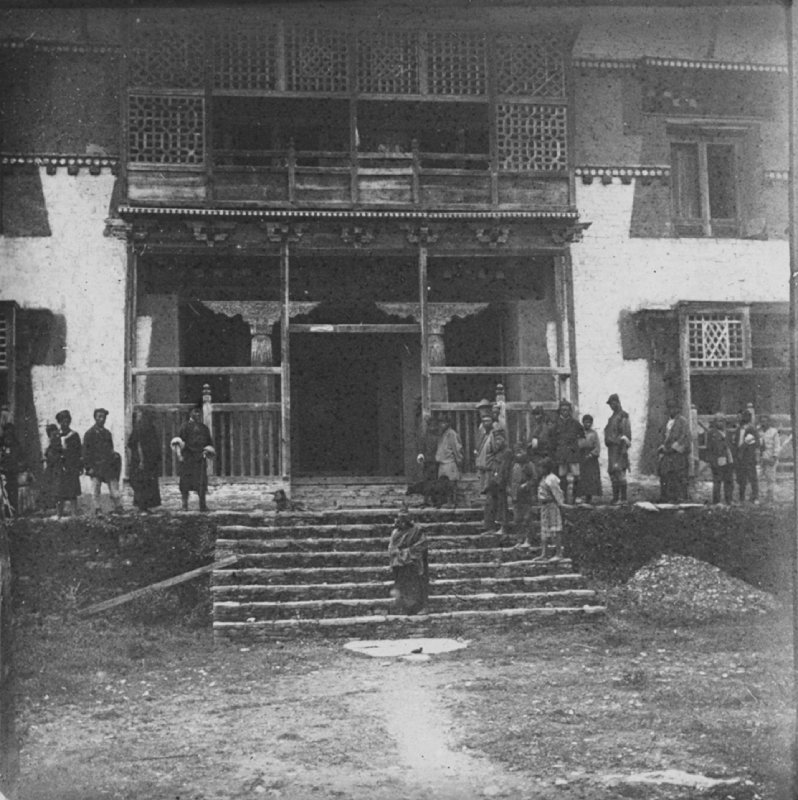

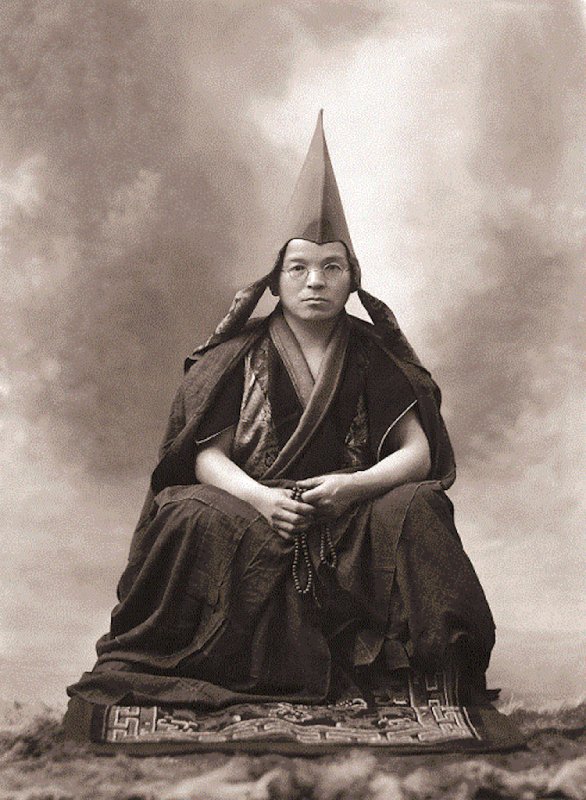

photographic collection. © École française d’Extrême-Orient (Paris)

Jacques Bacot’s scholarly publications, which span 1908–62, make recurring allusions to the author’s personal encounters with eastern Tibet and the people living in that region. This intimate link is central to understand how Bacot felt about Tibetan religious traditions throughout his life.

Bacot was born into a liberal Catholic family. Unlike other Europeans and Americans who were fascinated by Tibet at the time, Bacot did not convert to Buddhism. Yet he was undoubtedly committed to Buddhism as a distinctive sympathizer, as is clearly shown by his preface to Marguerite La Fuente’s 1933 translation of Lama K. Dawa Samdup and W. Evans-Wentz’s landmark rendition of The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Here, Bacot suggests: “The document revealed to us by Mme. La Fuente does not concern the ‘Amis’ (friends) alone, but all curious about Buddhism. Its interest and scope go beyond the boundaries of Buddhism itself by the gravity and universality of its subject.”

In referring to the “Amis,” Bacot meant something more concrete than simply general Buddhist sympathizers. Together with Grace Constant Lounsbery, a playwright, a translator, and the author of La Méditation bouddhique (Buddhist Meditation) (1935, foreword by W. Evans-Wentz), Marguerite La Fuente was a founding member of the French Buddhist Society, or Les Amis du Bouddhisme. While Les Amis du Bouddhisme (probably unwittingly) revived in their own right a pioneering trend of Parisian Buddhism from the 1890s onward, their main concern was to provide access to authentic Asian Buddhist texts and teachings.

The association was founded in 1929, and had been directly inspired by Chinese Buddhist reformer Master Taixu’s (1890–1947) visit to Paris (he was touring Europe and America at the time). In 1933, Lounsbery declared in a press interview that the society’s public events regularly attracted more than 400 people. In 1939, the society began publishing its own journal, La Pensée bouddhique (Buddhist Thought), where for 30 years translations of Buddhist texts as well as studies on Buddhism, with a focus on meditation, were published. Teachings by Buddhist monks and opinion columns were original features of this periodical. The society reached beyond national cultural borders and took an active part in the World Fellowship of Buddhists in the 1950s.

Several eminent intellectuals, artists, and scholars were its close associates, invited speakers, and contributors: besides Jacques Bacot himself, André Bareau, the noted scholar who specialized in the lives of the Buddha, and Alexandra David-Neel (who would later become honorary president of Les Amis du Bouddhisme), one should especially mention the sisters Suzanne and Andrée Karpelès—respectively a scholar of Pali and an artist inspired by Asian art, who spent part of their youth in India—who, like Bacot, were members of the Association française des Amis de l’Orient (literally, the French Association of the Friends of the East) created in 1920 in close relationship with the Guimet Museum.

The Karpelès sisters inspired their close friend Marcelle Lalou, a gifted painter herself, to opt for Buddhist studies in the late 1910s. Lalou would become Bacot’s student, colleague, close friend, and successor. This is but one example of the extraordinarily dense social and cultural networks surrounding Buddhist studies in Paris at the time.

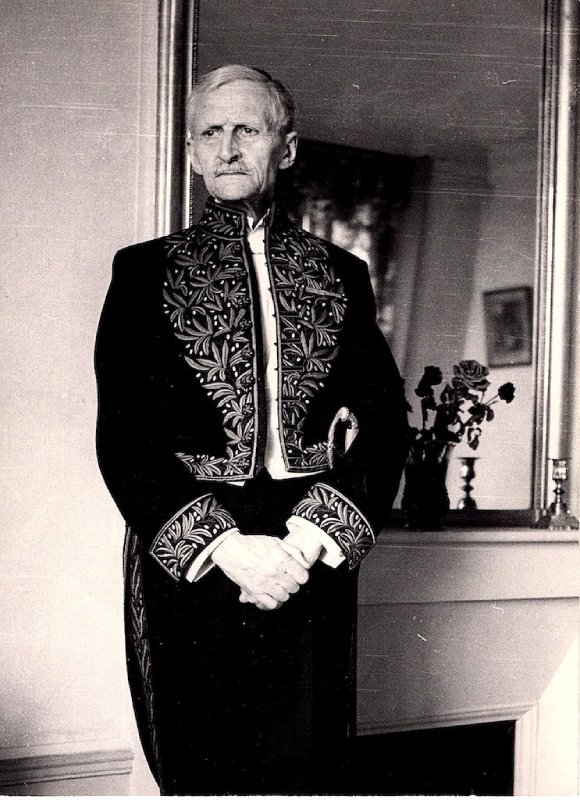

Paris, c. 1947. Jacques Bacot photographic collection.

© Private collection of Olivier de Bernon

Like many of his contemporaries in the interwar and postwar periods, Bacot was particularly drawn to mystical trends in world religions and advocated self-critical interfaith dialogue beyond the rigid and artificial divide between East and West. It was Bacot who prefaced the first volume of D. T. Suzuki’s Essays in Zen Buddhism (1940), translated into French by Pierre Sauvageot and the poet René Daumal and others for the three later volumes (1944–46). Here Bacot stresses Suzuki’s input as combining insights stemming both from within and without, bridging the gap between critical and apologetic approaches of Buddhism.

Bacot was also skeptical about the various forms of “neo-Buddhism,” or European (Theosophy-inspired) Buddhism, of his time. Indeed, in his popular work Le Bouddha (The Buddha) (1947), Bacot assumed that these Westernized fads were “artificial and standardized” interpretations of Buddhism, “without sap” and unable to “grow deep roots and far-reaching boughs.” Bacot’s contacts at the time are revealing in this regard. Returning to Paris from China in 1945, the noted progressive Catholic thinker Pierre Teilhard de Chardin became a regular guest of Bacot’s salon. Together with other illustrious specialists of Asian studies, such as René Grousset, Louis Massignon, Paul Masson-Oursel (the president of the Second International Buddhist Congress that was held in Paris in 1937), they founded the Union des Croyants (The Union of Believers), an association loosely connected to the World Congress of Faiths initiated by Francis Younghusband in 1936.

A significant figure in this group was Solange Lemaître, author of a biography of Ramakrishna and a close friend of artists such as Francis Poulenc and Félix Fénéon. Her books Le Mystère de la mort dans les religions d’Asie (The Mystery of Death in Asian Religions) (1943) and Textes mystiques d’Orient (Mystical Texts from the East) (1955) were prefaced by Bacot. In his introduction to the former book, Bacot wrote: “In aiming at the True beyond death one attains the most of truth beneath.” In the latter, he described Lemaître’s text anthology as a “luminous progress and a moving journey from summit to summit beyond the human spheres of the knowable.”

photographic collection. ©Ville de Digne-les-Bains

Last but not least, another familiar guest of Bacot’s salon at the same period and regular penpal was Alexandra David-Neel, the renowned explorer of Lhasa and French Buddhist icon who in 1925 returned to France from a 14-year journey in Asia. Bacot’s letters to David-Neel always end with discrete but heartfelt greetings to lama Aphur “Albert” Yongden, David-Neel’s adopted son and most loyal companion since their first meeting in Sikkim in 1914. These lines certainly strike the most intimate chord of Bacot’s memories of his own travels to Tibet, as they are clearly reminiscent of his adventures and “most solid and sure friendship” with Adrup Gönpo, whom Bacot had credited in Le Tibet révolté not only for being his language instructor, middleman, and “businessman,” but most of all for providing him unique access to Tibetan culture and sensibilities.

(Indre-et-Loire, France). © Private collection of Olivier de Bernon

A final anecdote helps us make the connections between travel, Tibetan studies, and the perception of Tibetan religions during this tumultuous yet intellectually fertile period. In his last opus, which drew heavily on his travels, Introduction à l’histoire du Tibet (1962), Bacot, as if remembering his quest for Pémakö, evoked the Hungarian savant Alexander Csoma de Kőrös, whom he—like many others until today—held as the first Western Tibetologist, and his quest in the 1830s for the elusive Śambhala (bde ’byung, Source of Bliss), the most famous of Tibetan Buddhist earthly paradises supposedly located north of the Himalayan range. Bacot then quotes an anecdote reported by George Roerich, son of painter, traveler, Theosophist, and pacifist Nikolai Roerich, whom he personally knew. In the story translated by Roerich, a pilgrim searching for Śambhala is told by a Himalayan hermit not to go further: “In your own heart lies the kingdom of Çambhala.” Of course, one could multiply the readings of this fable-like story across space and time, from Asian traditions and narratives to the origins of Tibetan studies in Europe and its spiritual/literary sublimations in the postwar period.

The relationship between academic research and a personal quest comes full circle here. Bacot’s trajectory was a balance that the French scholar wanted to maintain between reality and fantasy, insight and projection, discerning and dreaming. Here is eventually the crux of Bacot’s input to Tibetan studies in France and the pulse of his academic activity. Bacot stood out as a scholar and his studies have played a significant role in the reception of Tibetan culture and Tibetan Buddhism in Europe. Yet his vision of Tibet never surrendered to simplified narratives: rebel Tibet is here to stay throughout his work. This is where it should also be remembered that his writings flesh out his intimate experience of Tibet. While intersecting with his personal convictions and reflecting his own intellectual commitments, they are embedded in the personal relationships the French traveler had developed with Tibetans at a crucial stage of Tibet’s entangled history with Europe.

See more