This photographic essay takes us back to a time when opinions about Tibet were beginning to circulate in Europe for the first time. The essay is an invitation to freely stroll through formerly unpublished images of the few documented areas of eastern Tibet (historically known as Kham) taken from 1907–10, at a critical period in its history. In the process, a singular life trajectory becomes clear, that of the photographer’s awakening to Tibetan studies. Through the lens of the French traveler and scholar Jacques Bacot (1877–1965) and his alternatively impressionistic and sharp snapshots of Tibet, we can witness the emergence and materialization of the intersections between travel, academia, and the reception of Tibetan culture and religions in France in the course of the 20th century.

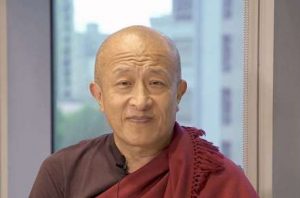

Adrup Gönpo, 1907 or 1909–10. Jacques Bacot photographic collection.

© École française d’Extrême-Orient (Paris)

A pioneering scholar and a pivotal figure of Tibetan studies in France, Bacot traveled in eastern Tibet for the first time in 1906–07. On his return to France in January 1908, Bacot’s collection was exhibited in the Guimet Museum. It was the first in France to feature Tibetan objects directly brought back from Tibet. In the aftermath of the 1903–04 British military expedition to Lhasa led by Francis Younghusband, Tibet was drawing wide attention in Europe. Bacot certainly developed a fascination for this still partly mysterious country while in northern India in 1904, a highlight of his one-year-long world tour and first long journey.

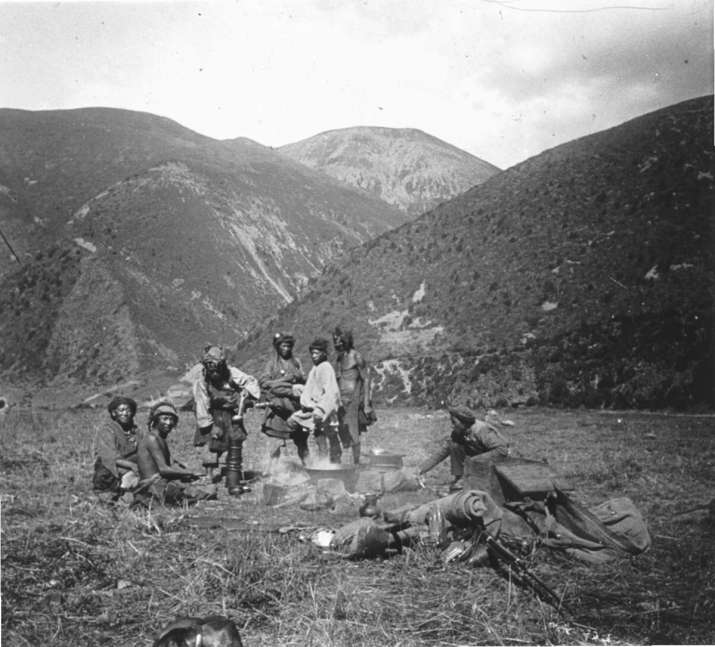

Nyakrong (ཉག་རོང་།), Kham (ཁམས་།), northwestern Sichuan, September 1909.

Jacques Bacot photographic collection. © École française d’Extrême-Orient (Paris)

Between 1909 and 1910, Bacot left Paris again for Kham on a journey that he had prepared for with the invaluable help of Adrup Gönpo, a former Bönpo lama from Dechen (Bde chen) County who had expressed a desire to go “on the other side of the ocean” and make the long journey to France. Together with his later sojourns in Darjeeling (1913–14) and Kalimpong (1931–32), Jacques Bacot’s exploration of Kham distinctively contributed to promoting Tibetan culture and religions in France and Europe.

Hosted at the library of la Maison de l’Asie in Paris this summer, a small temporary exhibition has displayed a selection of Bacot’s (for the most part) unpublished (and unfortunately originally uncaptioned) photographs stored at the École française d’Extrême-Orient, archive documents deposited at the Asiatic Society of Paris, and personal items from the private collection of Olivier de Bernon, one of Bacot’s grandsons. The exhibition highlights the French traveler’s decisive contribution to the history of Tibetan studies.

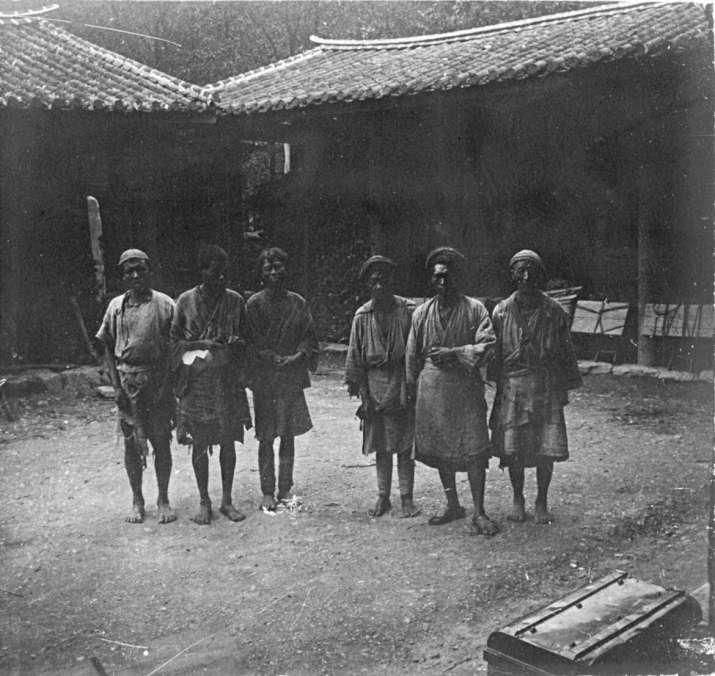

Kham (ཁམས་།), Tibet Autonomous Region (བོད་རང་སྐྱོང་ལྗོངས་།), July 1907.

Jacques Bacot photographic collection. © École française d’Extrême-Orient (Paris)

Although Bacot was far from a professional photographer, his images are invaluable as atmospheric and historical materials, heightened by their recent refreshed printings in the scope of the exhibition. Bacot almost exclusively used stereo cameras and plates, which were a popular medium at the time for art, education, and entertainment. Viewed with the appropriate device, called a stereoscope, stereographs create the illusion of depth and enable the viewer to enjoy a three-dimensional, quasi-immersive experience. It is no wonder that Bacot stuck with this equipment for his early journeys to Asia.

Much like his travel narratives, Bacot’s photographs provide evidence of the traveler’s open, watchful eyes and give flesh to his early sensitiveness to the Tibetan world. Bacot’s redefinition of Tibet needs to be understood amid the backdrop of the history of Western explorations of Tibet. Bacot himself stated that “Tibet is not only ice and wasteland” and he wondered: “Why stick to an image of the whole country from its uninhabited areas?” Likewise, Bacot praised the diversity, richness, and distinctiveness of Tibetan culture.

Jacques Bacot Photographic Collection. © École française d’Extrême-Orient (Paris)

Leaving France in November 1906, Bacot reached Dali in Yunnan in March 1907. From there, a lone European traveler accompanied by local personnel, he walked northward along the Mekong River. In Tsekou (Cigu) in Dechen County in May, he met Adrup Gönpo. All along the road following the east bank of the Mekong until Yerkalo (Tsha kha lho), they came across villages, Catholic churches (several Christian missions had settled in the area), and Buddhist monasteries reduced to ashes by the soldiers of the warlord Zhao Erfeng; so was the recent fate of Batang (’Ba’ thang), still in smoldering ruins when they arrived.

As they retraced their steps, Bacot, who at first had aimed to find a route to Lhasa, was told about an unexplored area called Poyul, southwest of the Mekong. On their descent, Bacot’s outfit made two incursions on the other side of the river into the “territory of Lhasa.” Although these proved unsuccessful, by doing so Bacot had a chance to partly follow the trail of the Khawakarpo pilgrimage anticlockwise, like the Bön po pilgrims. Bacot felt compelled to share his discoveries, and started writing a draft of his journey in his diary, stating that “the only purpose of my narrative is to make the reader travel across one of the most beautiful countries in the world.”

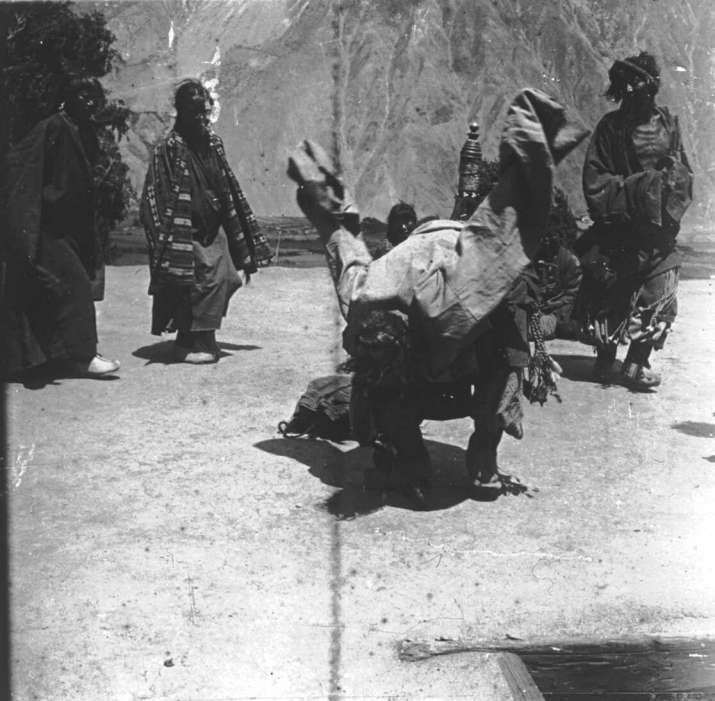

April or October 1907. Jacques Bacot Photographic Collection.

© École française d’Extrême-Orient (Paris)

Combined with a geographical and cartographic exploration of eastern Tibet, Bacot’s first trip was clearly meant as an ethnographic and anthropometric field survey. Even though it was meant for a broad readership, his 1909 travelogue Dans les Marches tibétaines (In Tibetan Borderlands) is still a goldmine for ethnographers and historians interested in the area and its ethnic groups, such as the Naxi/Mosuo, Yi/Nuosu, Lisu, Bai, and Derung. Regarding Tibetans, Bacot immediately distances himself from the idea held by academics and theosophists that Tibet was exclusively the land of “lamaism,” and that Tibetan Buddhism stood out merely as a degenerate mimicry of pristine Indian Buddhism.

Region (བོད་རང་སྐྱོང་ལྗོངས་།), July 1907. Jacques Bacot photographic collection.

© École française d’Extrême-Orient (Paris)

Reckoning the religions of Tibet as rich and diverse, Bacot paid acute attention to their multiple forms of expression: theater, music, dance, ritual, folk religion, pilgrimage. This no doubt makes Bacot a pioneering scholar of Tibetan studies. While his investigation called for an external approach to the landscapes and inhabitants of Kham, it quickly turned into a desire to access Tibetan culture from the inside as the traveler became totally immersed in his new environment: “Alone, living the life and speaking the language of another milieu, one ends up experiencing its effects and thinking in a new way,” Bacot lucidly observed in his Rebel Tibet (Le Tibet révolté), his second travel narrative.

To be continued in part two.

See more