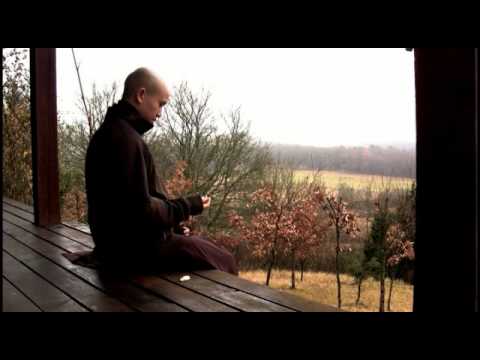

Who better to teach us about love than a modern master who once found himself in the same turbulent situation? There are many who might wonder what a “non-attached” monk like Thich Nhat Hanh has to say about this prickly question. But those who have not read his book Cultivating the Mind of Love (Parallax Press, 2006) may not be aware of the Zen Master’s first beloved. In fact, his story may be more challenging than others because he was a monk and she was a nun, and they never met again after they separated. Cultivating the Mind of Love is a compilation of Dharma talks that systemize his ideas on what it means to truly love. There are no clichés in this book; nor is there anything that neatly “fits” into preconceived stereotypes about Buddhist ideas on love. Thich Nhat Hanh’s conclusion is not only unique, it is deeply inspiring, scripturally informed, and demands great inner courage to accept.

Nhat Hanh begins his book with a poignant recollection of how he met an apprentice nun who treated him as her mentor, and how they dealt with their emotions whilst striving to heal ravaged Vietnam and revitalize Buddhism as a religion that cared about the young. He recalls how he first became a monk after seeing a picture of the Buddha on a magazine cover. After several years, love irrupted into his life, although he also notes that it is not some fixed event that happened in a past he has left behind. Love was always there and will be there after we are long gone:

“If you look deeply, you will be able to see your true, original face, and your true first love. Your first love is still present, always here, continuing to shape your life. This is a subject for meditation. When I met her, it was not exactly the first time we had met. Otherwise, how could it have happened so easily? If I had not seen the image of the Buddha on the magazine, our meeting would not have been possible. If she had not been a nun, I would not have loved her” (p. 15)

To gain wisdom and insight, one’s emotions must be acknowledged. Nhat Hanh recalls that he tried to tell her of his love by speaking of other things, and at the end of it all, she confessed that she did not understand a word (p. 18). But she did in fact understand, and she tried to resist, but could not. They accepted the Noble Truth of their love. But as Nhat Hanh fondly notes, their work together revitalized Buddhism as a force for social justice and relevance in Vietnam, realizing their dreams of bringing healing to their nation. She was like a princess, and his bodhichitta was her guardian (p. 23). Their strong desire to realize the Dharma protected them both, and they were able to love genuinely within the dignified limits of their calling as Buddhist clergy. Although his Dharma brothers were understanding and compassionate about his love, the nun’s fellow sister was not so confident. Taking a courageous step, they acknowledged the need to devote their full effort into making Buddhism a truly social force in Vietnam without each other.

“I remember the moment we parted. We sat across from each other. She, too, seemed overwhelmed by despair. She stood up, came close to me, took my head in her arms, and drew me close to her in a very natural way. I allowed myself to be embraced. It was the first and last time we had any physical contact” (p. 27).

It has since been many decades, and Nhat Hanh can only point to the letters that he wrote to her but she never received. The Zen Master shares with his students many other losses he has endured, among them a close brother who was probably killed during the Vietnam War and a nun who felt abandoned, lost hope and left the Order. His love story is by no means a fairy tale.

But for Nhat Hanh, love does not stop at tragic endings. In the spiritual life, separation and death do not have the final word. As he points out beautifully after finishing his story, “What happened next continues today.” In other words, to ask him “what happened next”, or to be dissatisfied with what seems to be an unhappy ending, is to miss his most important message: When we are stuck in the notion of a self and a life span, we cannot understand true love, which is reverence, trust, and faith. An individual’s love is also made of crucial non-self elements, such as her ancestors, the mind, nature, and the cosmos. Seen this way, where does love begin and how can it end? Our limited questions, centered on the self and a time span, suddenly seem to lose their power. Love is simply self-less, always present. There is no difference between a human being’s love story and the Bhagavan’s teachings. By growing and cultivating deep self-respect, the people we inevitably lose are able to stay with us and influence our lives (p. 32).

Thich Nhat Hanh then gives an engaging commentary on several different scriptures that describe the non-self way of loving. The Dharmakaya, or Body of Truth, is always present and alive. There is no need to worry that the historical Buddha died two thousand five hundred years ago. It was a compassionate illusion that he created to teach his disciples that all physical things must pass away without exception. Being unconditioned, however, the Buddha is really present. Aware of this high reality, Thich Nhat Hanh does not worry that he did not meet his first love again physically. Their stories met in love, and it was a true blessing that the Bhagavan guided them to each other.

In human relationships, love must be experienced in order for it to be alive. This book is also one that is not so much read but experienced. The contents within were sermons given by the Zen Master. It was only later that they were published in the hope of benefiting a global readership. This book opens up the mind of love, which will make one more receptive to awareness and wisdom. But awareness needs to be answered by action. It is not enough to be aware of love; one must actually love. It is up to those in the vocation of discipleship to realize this challenge.

Cultivating the Mind of Love can be ordered online through Parallax Press or at any good bookstore or Buddhist bookshop.

Back to Plum Village Schools and Educators’ Retreat, April 2013 special edition homepage

Back to Thich Nhat Hanh Birthday Edition 2012