“Tear my skin, drink my blood, eat my flesh, chew my marrow, lick my brain, end up my dot.”

I was sitting next to Baba-ji, listening to him in a cloud of sacred smoke inside his hotel room, where I was staying with my partner and two friends. We were listening to Baba-ji in a state of totality, trying to record his eloquent words, seeking to integrate his teachings and attain his state of being.

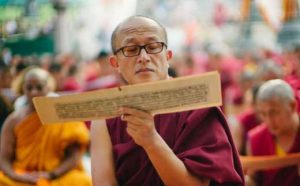

Baba-ji was always in that state of unshakable generosity, giving the fire of his intense devotion to his beloved, whom he called “Ma”—the Great Mother, the goddess, the creator, the lover, the life-generator present everywhere and in everyone. He made his love so palpable through his own presence—a love he embodied entirely. Always laughing and joking, but mostly mocking us, he teased our seriousness and our attempts to understand his teachings through intellect and meticulous notes. He would laughed: were we feeling it? Could we be “it”? He asked us directly: are you feeling love? Can you feel the fire of Sahaj? Can you surrender to the passion of the guru?

Baba-ji’s eloquence seduced our minds while simultaneously inviting us to surrender to pure wisdom and the immediacy of sensation. He encouraged us to move beyond intellect into the realm of presence, using the physical doors of our senses to access the invisible within us—a dimension with no place, no size, no direction, no purpose. It was a paradox of mind and heart. For 10 days, he led us with full dedication, teaching four Westerners who had traveled so far to his home and further on a pilgrimage to the holy tantric sites of Sikkim, northern India.

We had journeyed along treacherous roads that followed a wild river, shaking our brains and bodies like disoriented animals in an earthquake. Driving, through deep valleys and thick forests, we stopped at historical monasteries, high peaks, and waterfalls with caves where ancient yogis had meditated, including Padmasambhava himself. The legendary Mount Kanchenjunga loomed large in our imagination with mystical stories of a secret hidden land. It was said that those who reached this land would be forever joyful, liberated from all kinds of suffering in an eternal state of samadhi, never to return to the Wheel of Yama: samsara.

The indigenous habitants of Sikkim, known as Lepchas, believe Mount Kanchenjunga to be the abode of the deities. Their spiritual practices are closely tied to the land, rivers, mountains, and forests. Lepcha folklore speaks of Mayel Lyang, a mystical hidden land described as the “Land of Eternal Bliss.” This land is believed to be the original home of the Lepchas, created by the divine couple Itbu-moo and Tashey-tong, central figures in Lepcha mythology. Similar myths, such as the Tibetan legend of Shangri-La, also reference mystical realms hidden in the Himalayas.

The four of us, shaken to our cores, were inspired by the many stories. They fueled our motivation to meet the “Bengali Baba” as he was known, who lived in Kalimpong with his consort, Shodashi Ma. The sacred secret land was described as both an actual place and a state of being to be reached within our own psyche. This duality mirrored our journey—both the rugged outer pilgrimage and the inner spiritual path we walked alongside the guru, his blissful consort, and a few of his disciples. Baba-ji spoke in riddles, between sips of blessed alcohol from his skull-cup. His long lectures were punctuated by spontaneous laughter, praises to “Ma,” and sudden dances when he would play his single-stringed instrument, the ektara.

Baba-ji had once been an Aghori sadhu. The Aghori tradition, a mystical and ascetic sect of Shaivism, is known for its extreme spiritual practices that challenge societal norms. Rooted in non-dualism (Advaita), Aghoris see no distinction between pure and impure, sacred and profane. Everything in the universe is seen as an expression of the divine, including what is traditionally considered taboo. They meditate in cremation grounds, use human ashes in rituals, and employ skulls as bowls (kapalas) and femur bones as trumpets (kangling), symbolizing their detachment from the material world. These extreme practices are undertaken to reach enlightenment (moksha) in this very lifetime.

For those who seek purity, life and death are the same;

in ash, we find liberation;

in shadow, the light unfolds. — A quote inspired by the principles of Aghori philosophy, no source

Having followed his own guru on the path of an Aghori, Baba-ji’s path later softened, and he adopted the white-and-red nagpa shawl over a blue vest. The nagpas, associated with the Nyingma school of Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism, propagated by Padmasabhava, who changed the cultural and spiritual landscape of the Himalayas, live a non-monastic, yogic lifestyle. Like the Aghoris, nagpas also engage in esoteric practices that focus on transformation, meditation, and non-duality. However, they can also maintain a family and a home life, integrating spirituality with the everyday.

I was mesmerized by Baba-ji’s trajectory, knowledge, and devotion. He pulled tears from my eyes, and challenged my thoughts and conceptual constructs. He threw me from devotion’s abstract flow with his music and smoke to the sharp view of reality, offering us a full spectrum of all experiences. Some surrendered to his music, others to his smoke, and others to their notes. Baba-ji gave us everything without asking for anything in return but our presence. Likewise, Shodashi Ma, in her silence, was rooted deeply in her cherished love for the divine through yogic practice and hours-long rituals. Her deep presence resonated with profound love for each and every being and place she encountered.

Sitting at my desk in Brazil, my memories of those experiences feel like a dream, another dimension, another life. Yet they are not. These practitioners live in the same world as I do, reminding me that my heart can also touch the same love-trance and sharp lucidity they embodied.

We considered bringing Baba-ji to the West, to share his precious wisdom and touch the hearts of those who long to play, to dance, and to sing the poems of the enlightened ones. But we could not imagine how Baba-ji, with his dreadlocks, nagpa attire, and skull-cup, could teach in a place like New York City. Would we be prepared to subtract the context in which we live in to see someone as he truly is? Or would he become just another exotic figure, a subject for social media selfies? Would fame in the West corrupt his path, even if he accepted no payment, even as an offering from us?

I came to believe that his land—his home with its specific landscape and challenging roads—was integral to the sacred geography that allowed us to access his teachings; sacred not because the land is covered in gold, but because our motivation to meet the guru in his abode opened the invisible sacred gates of Sikkim, the source of so many sacred legends. Certain places on Earth do seem to sustain those who carry fire in their hearts, like a mountain with a lock that can only be opened by the fire we carry within. Without that inner fire, one could stand at the gates of heaven and never be able to enter. From this perspective, Shangri-La may indeed be a place, but the key to it is the invisible fire. The Himalayas are full of “fire-holders” for a reason: the geography is made for fire-holders. What would happen to fire-holders in an environment like New York?

Reflecting on this, I ponder the meaning of pilgrimage and the importance of going to certain sacred places. Effort is central to pilgrimage, as demonstrated by the many Tibetan pilgrims who travel to Mount Kailash, the holiest of mountains for Buddhists and Hindus, not by walking but by prostrating over a journey of months. Would the merit be the same had they simply walked or ridden a horse? Perhaps the fire that must be found before reaching the sacred place must be kindled through physical effort. As Baba-ji taught, the five senses are the secret gates to eternal bliss.

Whether through pilgrimage, yogic discipline, devotional pujas , or volunteer work, involving the body ignites the fire that can open doors of bliss. When a pilgrim reaches the sacred Mount Kailash after arduous physical effort, or when a true yogi attains bliss after years of persistent tummo or kundalini practice, it’s the fire within that opens the gates. If Baba-ji were to go to New York, the meaning of the sacred geography—a symbol that the Earth’s distant primordial wisdom—would be lost. The faraway nature of such places reminds us that before any encounter, we must seek the key within ourselves. Baba-ji held the key, but he could only show us the way; he could not open the doors for us.

Back home, so far from that magical place, my intention is to keep the fire alive—to become a fire-keeper, longing for “Ma” and resisting my longing for fake gratification and the comforts of worldly distractions that extinguish the flame. When the fire burns, it can be blissful or terrifying, but we should not ignore the ache of a longing heart. My calling is the song that I must dancing to until I reach the gates of Shangri-La.

By passion the world is bound; by passion too it is released.

But by heretics this practice is not known,

For they pass from existence to existence. — From the Hevajra Tantra

See more

Tiffani Gyatso

Yangchenma Arts & Music

Related features from BDG

The Magical Kingdom of Bhutan

Inner Sanctuaries and the Temples of Tibet

Creative Happiness: A Journey through Suffering and Joy