Early Buddhist writing delivers its share of patriarchal material. Women are described as “the stain of the holy life” (SN 1.76) and “a snare for Mara” (AN 3:68). They are also described as dangerous temptresses and the image of their decaying bodies in charnel grounds are used as teachings for monks struggling with desire. For a predominantly male monastic community, women can be obstacles to be overcome.

Intellectually, I can appreciate the rationale. These types of passages attempt to steer male audiences away from the distraction of (hetero) sexual desire. But I cannot credit the authors too much: there is nothing kind or compassionate about the accusations made against women in the name of awakening. The authors of early Buddhist literature repeatedly chose to guide their male readers away from women by insulting them. I am quite certain such illustrious thinkers could have found alternative means had they made just a bit more of an effort.

But I will not discard all of Buddhist literature because of some of it. On some days, I read past the denigrations and look for something more inspiring instead. On other days, I stay with the ugliness and wait for some kind of wisdom to tell me where to go. But when I encounter positive portrayals of women, I always cherish them. I read those passages over and over, almost as though I am trying to wash my eyes clean of the hurt previous passages created. I raise the positive portrayals up and shine a light on them, because Buddhism is more than its moments of misogyny. If I didn’t believe that, there would be little reason left for me to stay.

I recently came across a precious moment of female-focused inspiration in the pages of the relatively obscure collection known as the Mahāvastu. It is just a few lines—a small scene tucked away in what is a much larger and more dramatic narrative—but it is so lovely that it deserves a moment of recognition.

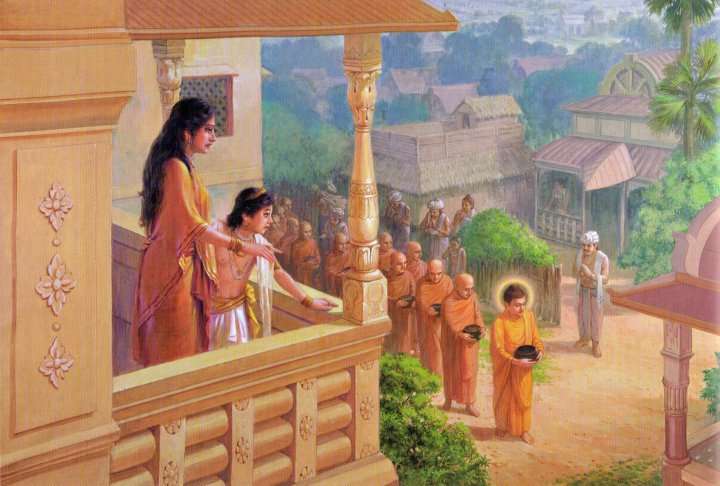

The story takes place during the Buddha’s return home after he attained awakening. The Buddha was residing in a park not far from his hometown of Kapilavastu and the king decided to bring the entire Śākyan community with him to greet his illustrious son.

The Buddha was aware of their approach and wondered how he should greet them upon arrival. He knew that the Śākyans were a proud people and that if he remained seated, they would be offended. But if he stood up, all of their heads would shatter as a result of the power of his cosmic sovereignty. He therefore chose something different: he lifted himself into the air and met his community while floating above them (a smile is surely required here).

After generating the necessary gasps of astonishment, the Buddha proceeded with a magical display of his powers, transforming the upper part of his body into water and the lower half into flames. Then he switched things around and transformed his lower body into water and his upper half in flames. Then he transformed himself into a bull that vanished and re-appeared in various places in the sky, and then he turned himself into a fountain, spouting water in all directions.

Mahāpajāpatī (the Buddha’s stepmother) and Yasodharā (the Buddha’s wife) were in the crowd with the other Śākyans, witnessing this extraordinary event. Mahāpajāpatī, however, could not see any of it because she was blind.

Her blindness is a detail I have not encountered elsewhere, but according to the Mahāvastu, Mahāpajāpatī cried so many tears after her stepson left home that her eyes were filled with scales and she was blinded as a result. She could hear everyone around her gasp with delight at the Buddha’s display, but she could not see any of it and asked Yasodharā to describe what was happening.

Realizing that nothing she could say would do the moment justice, Yasodharā instead cupped her two hands together and caught some of the water that was pouring out of the Buddha’s body as he performed his miracle. She then brought the water to Mahāpajāpatī and bathed her eyes. The scales fell away and Mahāpajāpatī’s sight became as clear and faultless as it had been before.

The story continues after this moment, focusing on the Buddha and his father, keeping the male protagonists at the center of the narrative, but the scene of these two women is nevertheless included, and it is tender and kind.

Women are so often described as competing temptresses whose sole purpose it is to disturb the spiritual pursuits of the men who left them behind, but in this story, another picture has been captured. Two women, who do not speak to anyone but each other, and do not ask anything of anyone, wander quietly onto the scene and manage their suffering by themselves, finding a solution without having to ask a man—any man—for help.

Yasodharā feels compassion for her mother-in-law and finds a way to heal her—something Mahāpajāpatī never even asked for. The quiet dignity of these two women in this scene, their cooperation and mutual kindness, is touching. They are lost in a sea of male characters and no one around them appears to even notice them. They are invisible and virtually silent.

But they are visible to us. And by taking a moment to notice them, they remain visible to us. They continue to be seen.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Kisa Gotami Meets Beyoncé

In Conversation with Vicki MacKenzie on The Revolutionary Life of Freda Bedi

Why Education Matters: Improving Female Empowerment and Health Practices in Nepal