The mutual influencing and interweaving of Taoism and Buddhism in China is a vast, centuries-long integration that took place on many levels: religious, social, artistic, philosophical, poetic, and martial. As such, the subject of their mutual absorption is essential to any serious study of Taoism, Buddhism, or China. More than that, the study of their structural co-existence is at the same time complex, subtle, and overlapping.

Taoist martial arts, known as internal martial arts, derive ultimately from longevity practices with the aim of achieving immortality. Buddhist martial arts, known as external martial arts, derive from combat, with the objective of invincibility. When Taoism and Buddhism met in the sphere of monastic martial arts, the concepts of immortality and invincibility also co-mingled.

It is important to point out at this early stage of the discussion that there are fundamentally divergent attitudes at the core of Chinese and Western culture. China displays with pride the Three Teachers, Lao Tzu, Confucius, and Buddha, as the essence of Chinese religious practice and legacy. Excellent ideas and practices are honored and brought together. By contrast Western religions fight, conquer, and abolish other religions and traditions, and do not, as a rule, adopt potentially useful concepts from other religions. The coming together of Taoism and Buddhism in Chinese monastic martial arts is in itself a reflection of a fine quality in the character of Chinese culture.

This short series of articles will examine some aspects revealing the influences of Taoism and Buddhism in Chinese martial arts. This article presents the 108 Luohan System of martial physical training taught at prestigious Taoist monasteries in the early 20th century. Luohan are otherwise known as arhats, semi-saints in Buddhist lore, not quite bodhisattvas. Eighteen eventually came to be the customary number of luohan in art and legend, and these 18 personalities correlate with Buddhist principles and actions of some kind, such as meditating, or taming a tiger.

There are many versions of the Luohan Quan as it is known. That practiced by the Shaolin monks today is a set of basic physical exercises. In southern China, at both Taoist and Buddhist monasteries, the 18 luohans expanded into multiple movements per luohan, creating a system of 108 training exercises and the accompanying mental actions of concentrating on a virtue or imitating an animal.

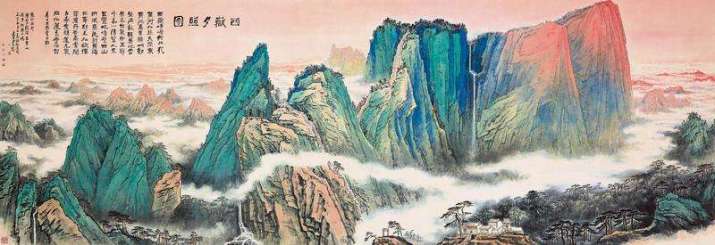

There are not many accounts of life in a Taoist monastery before modern China, and even fewer translations. Standing out among them are Thomas Cleary’s translation of Wang Liping’s training as a Taoist wizard, by three Taoist wizards of the Dragon Gate sect, Opening the Dragon Gate (Tuttle 1996). Another gem of destiny is the life story of Guan Shihong, who entered South Peak Temple on Huashan, one of China’s most sacred mountains, when he was nine years old, in about 1920, when his aristocratic warrior grandfather asked the grandmaster of Huashan for a personal favor.

Guan Shihong is the only wizard of the Zhengyi-Hushan sect to have lived outside of China. In California, another Chinese-American, Deng Ming-Dao, chronicled his teacher’s life, training, and teachings. The accounts are a small miracle of devotion: The Wandering Taoist (Harper 1986).

Wu Chanlong of the Taiping Institute explains that the 108 Luohan Quan learned by Guan Shihong is a very elaborate system that includes more than 108 forms, with 18 of them being considered the root. There are sets, such as the 18 Methods of the Arhats, Small and Large Arhat, Tiger Taming, 18 falls of the Arhats, Drunken Arhat, and also Gorilla Boxing, the Eight Steps, Plum Blossom, and more. There are also armed practices, with 108 weapons sets, including 35 forms for long weapons and 72 for short, and over 24 combined combat sets. These are all part of the 108 Luohans.

The 108 Luohans was a Buddhist martial style that included three parts: calisthenics, making the body light, and self-defense. This comprehensive training was used at South Peak Taoist temple in the 1920s, especially for boys aged about 12. Guan Shihong explains: “The 108 Luohans was a Buddhist martial system that had come to Huashan during the Tang dynasty, when Hindu, Buddhist, and Taoist masters, uninterested in religious factionalism, had gathered to exchange knowledge. Finding similarities between Kundalini yoga and Taoist meditation, the Taoist and Hindu masters intermingled the physical techniques, even while retaining their allegiance to their respective gods. The Taoists taught the Buddhists blood-circulating meditations and internal exercises. In turn, the Buddhists gave the Taoists their external martial art, the Luohan system.”

The Luohan system was fun to learn and easy to memorize because each Luohan had a virtue and an action. Huashan is a legendary mountain, dangerous, mystical, with various micro-climates and weather systems. For a group of eager competitive young Taoist novices, the entire mountain became a training ground. In particular the Luohan exercises for making the body light could be brutal. The master would shove the boys off of cliffs of varying heights, invariably causing some crashing discomfort.

“But look how the deer jumps up the mountain, raising its center of gravity,” they’d be told. “And look how the tiger hunches down the mountain, slowly, forelegs extending as the center of gravity is held back. Look how they make their bodies light.” In time, Guan Shihong could land on his legs no matter how he was thrown off the cliff; he could land on one leg, he could land on his hands, he could land seated. He could jump up a mountain, and come down with stealth.

After two years, the 108 Luohans were learned. Only upon completing the 108 Luohans, with the externals thereby strong, could the internals of herbalism and Taoist qigong be taught. Buddhism in the martial arts has much to do with the concept and preparation of protection. Taoism in the martial arts has much to do with transformation. Subsequent articles will explore these aspects of immortality and invincibility.

See more