Writing this article during the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, I am drawn to wonder how this virus, one out of millions of viruses on earth, has brought out the worst and best of humanity around the world? The coronavirus seems so symbolic. It can be anything that scares and separates people, causing prejudice, hatred, violence . . . but I have a deep faith in the human capacity to connect. Let me share a story with you.

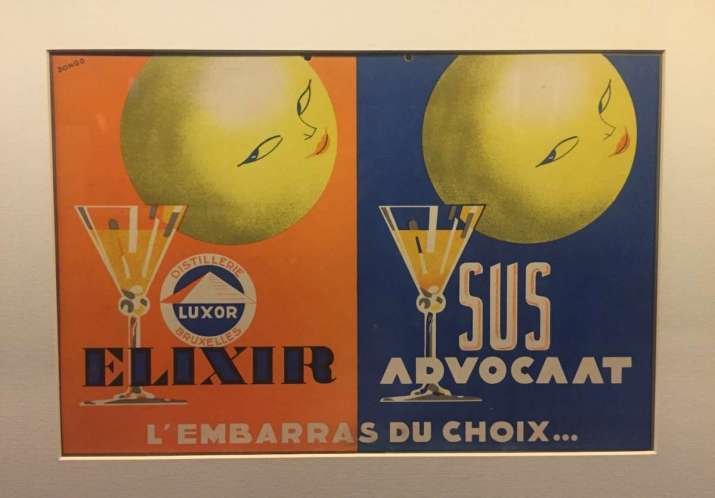

One summer, after attending a wedding in Oslo, I traveled around Europe, going to places old and new, catching up with friends here and there: La Seine, the Vienna State Opera, Museum Island in Berlin, the Temple of Poseidon outside Athens . . . drinking almost everyday. However, I was completely sober during my stay in Belgium. I was visiting a Chinese Buddhist monk friend of mine, and Chinese Buddhist monastics follow hundreds of rules, no drinking being one of them.

In fact, the venerable was the first Buddhist monk that I had ever known. When I studied art history in London, I wrote a thesis on ceramics used as religious offerings in late Imperial China. Literature on ceramics is abundant, but practices about offering ceramics were obscure. Having seen the venerable in monastic robes around the university library a few times, I decided to approach him for inside knowledge. Soon after that, he went on to pursue a PhD in Buddhist studies in Belgium. For me, the connection with Buddhism took me on an unexpected and inspiring journey: I delved into the study of Buddhist art, worked with Buddhist monasteries, and even started writing a column on Buddhism. So, I’d always wanted to catch up with my friend and I had never been to Belgium.

Where the venerable lived was interesting. It was a care home for retired Catholic priests. Situated in an affluent district of the city, the residence was thoughtfully designed for the comfort and convenience of the elderly. Moreover, the rent for external residents and guests was very friendly. Because of a personal connection of the dean of the Theology Department at his university, the venerable and his fellow students from overseas were offered accommodation here. Given the favorable conditions, I stayed at the residence for five days, while taking day trips to other cities by train.

On the first day, the venerable showed me around the building. He told me that the average age of the priests was over 80. Devoted to the Don Bosco order, they had traveled to different parts of the world, set up schools and colleges and helped to improve local education for the young people. Now they had returned to their homeland, but with almost no relatives. The parish took the responsibility of providing for them and volunteers came in to cook and clean. But each priest had his own room and lived with great self-reliance.

In the beginning, the venerable tried to help them with practical things, such as getting cutlery, because in Chinese culture, this is a virtuous way to take care of the elderly. But he soon realized that it was not appreciated here, so he stopped. There were more differences between them. For instance, while the monk and the priests all practiced celibacy, Chinese Buddhist monks do not eat meat. Nevertheless, the venerable did not seem to be bothered by any inconvenience. At the end of the tour, he explained the meal times and showed me where the food and drinks were in the kitchen. “I heard they also have a wine cellar, if you like wine,” he added.

Oh, I love wine! Even up to this day, although I have become a Buddhist, I could not take the precept of no drinking for the laity. I know that Catholic monks drink wine, and they even make wine—very good wine, actually. But I never went into the cellar. I did not want to drink alone, and I did not know whether the retired Catholic priests wanted to drink with me. They look so stern and serious. Strangely enough, they spoke all the languages in the world except for English: Flemish, French, German, Italian . . . I haven’t forgotten all my French yet, but what would we talk about? We had nothing in common, in terms of culture, religion, or gender. Perhaps they perceived me as a sinful Chinese girl? Maybe they would want to convert me?

So I kept myself busy. The venerable was occupied with writing his thesis. We only had one proper talk one afternoon. The rest of the time, I tried not to disturb his academic and ascetic life. So on my own, I visited several sites and many museums in Belgium.

On day three, at breakfast, the venerable introduced me to two priests who spoke English. Father David had stayed 20 years in North America. He told me with great pride how he had driven across the US. He had also been to Vietnam and Hong Kong, which gave him some knowledge about Asia. Father Antony had spent more than half of his life in the Congo. He spoke emotionally that he was going back to Congo soon, despite his old age, because he saw the country as his second home.

“They are actually jovial,” I said to the venerable after breakfast. “Yes, they are,” he replied. “Sometimes they sing funny songs together, out of the blue in the middle of a meal. It is good that they keep each other company. This year, so far, two fathers have left us.”

What a life, I thought to myself. The world has changed so much. In ancient times, people who chose a spiritual path were placed in the highest position in the social hierarchy, above aristocrats, warriors, farmers, and traders. Now the order is completely reversed. Monks and nuns across religions are considered a strange identity. These retired catholic priests are probably the most educated men in the Western world, but a disappearing breed. My Buddhist monk friend has also had many challenges. The world’s oldest university, Nalanda in India, was a monastic centre, but now he had to obtain a degree in Buddhist studies in a Western university. Moreover, having vowed to abide by so many monastic rules, he found himself living in a culture that encourages personal freedom. Indeed, to practice spirituality in our time requires so much self-discipline and will power, and the mental capability to deal with loneliness.

On day four, I missed breakfast. I woke up late because I was exhausted from my day trips. The table had been cleared. I entered the kitchen and had my breakfast at a side table. Next to me, a beautiful yellow canary was chirping in its cage. This time, Father Anthony walked in. “Bonjour,” he said to me, and walked straight toward the canary. He mimicked her singing as if he was talking to her, and chuckled.

Unexpectedly, he turned his head to me. “Do you know what she is saying?”

“I have no idea Father, there are many languages that I do not yet know,” I replied.

“Oh, I know.” He sounded a little mischievous.

“Really? Please tell me then,” I smiled at him.

“She said,” Father Anthony cleared his throat: “—it is good to be alive!”

That could have been a moment of sudden enlightenment in Chan Buddhism. I was surrounded by immense bliss and I felt tears in my eyes. “I see, Father,” I mumbled.

“It is good to be alive,” he repeated and exited with heartfelt laughter.

The next morning, I arrived for breakfast on time, but did not see Father Anthony. I was told he had left the previous night for the Congo. I had wanted to say goodbye, but I guessed that our farewell had already been said in the best possible way. I myself was leaving the following day, early in the morning. I could not explain why I felt melancholic. Perhaps about fleeting time? Perhaps about leaving this place that I had initially found so distant?

“I am going to Italy tomorrow and the Vatican,” I raised my voice and made an announcement in French. Finally, I found a way to express my respect and appreciation for the life vocation of the fathers. Before I left, I wanted to make a connection with them. Sure enough, their faces lit up. Some started to chatter in languages that I did not know, some asked me where I would be visiting. “Are you going to Turin? We all studied there . . .” Father Antoine asked me.

You see, this world can be so confusing and overwhelming. Do not expect to solve all the puzzles with your mind. Our minds can only analyze based on the things we know or that we think we know. Real understanding starts with an open heart. No matter how many differences lie between us, we have the same human existence; we have the same instinct to connect with each other. Let there be no conflict within you, no conflict between us. We can move forward together.