In her childhood memories, her mother’s garden is filled with lilies, peonies, roses, with oak, fig, and pecan trees, and the lush green grass of Texas. Japanese architectural pieces and outdoor sculptural elements such as the tōrō, a traditional Shinto shrine lantern, graced the yard. The tōrō is now resting in Lindy Pollak’s San Francisco hillside garden.

Japanese roots

The design of her family’s garden in San Antonio was heavily influenced by their stay in Tokyo and Yokohama in the early 1950s. Later, living in France, the lovely gardens and parks were an integral part of their lives, and inspired the design of certain elements in their gardens in Texas. Lindy’s father had been studying to be an architect at the University of Texas before he joined the army in 1942. His bent towards architecture and design seems to have influenced Lindy’s eye for line and form, though she doesn’t recall seeing any of his models or studies. She did, however, inherit his drawing tools. Lindy now uses these tools for her botanical drawing classes. Her mother Cora’s deep interest in horticulture, which was expressed on their modest estate in San Antonio, included knowing all the Latin names of plants, drying them, and hybridizing orchids and lilies. As a true horticulturalist, she ran a small plant business, traveling with the garden societies, always learning and trying new things out at home. She founded several garden societies, and won many awards in the Horticultural Society circles, accumulating a whole wall of prize ribbons. One year she even won “Garden of the Year” in the competition Beautify San Antonio.

Perhaps it was predestined that Lindy would be interested in aesthetics, plants, and art. Her early memories of Japan, when she was about nine years old, are still vivid. And from ages 10 to roughly 16, Lindy’s disciplined daily piano practice back in San Antonio occurred facing a silk-embroidered image of Mount Fuji. Recently, while sorting family possessions, she found photos of their living room in San Antonio with the piano and the familiar image of Mount Fuji on the wall near a folkloric shadowbox scene. These Japanese artifacts illustrate the time when she was seriously practicing Mozart, Bach, and Schubert, whose lyrical melodies are imprinted in her. Along with an interest in botany, music, and art, Lindy’s family nurtured a keen interest in textiles, collecting silks and kimonos, with her mother adept at crotchet, fine embroidery, and sewing.

Horticulture and design

As an adult, Lindy’s friends would often ask her for advice about their gardens, and she found it a socially engaging way to work with others. Having worked in the corporate world for a long time, and knowing that it wouldn’t last forever, she wondered what would be next. She moved to California, and having an interest in landscape design and horticulture, switched careers to work for plant nurseries in Marin County. In the Bay Area, Lindy studied landscape design at UC Berkeley Extension. She wanted to design and work with people in their gardens, rather than draw up plans all day at a desk. She learned how to make schematic drawings for landscape work, and then established her own design business, Meander.

Upon retirement, and now living in San Francisco, Lindy studied botanical drawing and painting for three years with Mary L. Harden, where she learned the basics of drawing and painting, hand-eye coordination for the analysis of subjects, and the basic color and transparency exercises for becoming a watercolor artist. Her interest in the watercolor classes was catalyzed by an exhibit of watercolor paintings at San Francisco’s Botanical Garden Library, curated by Mary. Encountering images of flowering trees and plants, Lindy felt that painting such images was what she wanted to learn. In the winter of 2014, soon after she had visited the exhibit, a light bulb turned on and she signed up for a beginner class. During the first nine months of the course, she was simply drawing with pencil, pens, rendering various subjects. Then she learned 17 specific pigment colors that Mary felt were best for beginning botanical painters—limiting the range to transparent watercolors. Lindy has since extended her palette in a watercolor workshop with Berkeley watercolor artist Julie Cohn, titled Imaginative Landscapes with Reflections and Trees. Lindy has always lived under large trees. In San Antonio it was enormous oak trees. She describes the comfort of the large overhanging branches, as an “all-embracing umbrella of permanent green!”

Color and fire

With an artist’s eye, she watched the skies during the recent fires in Northern California. She says the colors were very unusual, as the ash in the atmosphere reflected light in new ways. The clouds held hues of red-gold, Prussian blues, and tangerines caused by the water vapor meeting ash in the clouds: such beauty above, such tragedy below.

Working on a new botanical study, Lindy tried mixing pigments to match the same tonality as the interior sepals of a clematis flower, but couldn’t yet emulate it. Then a new paint tube arrived in the mail with a Minnesota Pipestone hue, and it was the exact match for the veined area. She finds it endlessly pleasurable to mix water and pigment on paper to see what happens, even when the result is often not what she had expected. As her creativity blossoms, she is looking to broaden her range of exploration in watercolors. Now that she has some foundation in technique, the next step is to develop her own personal style.

She is taking a Chinese Brush Painting class at San Francisco City College taught by artist Ming Ren, which offers a new painting process and approach. She hopes to explore peonies, lilies, chrysanthemums, and poppies in the Sino-Japanese sumi-e brush tradition, which trains the eye and hand in a way that she has not yet tried. Having lived in France as a teenager, Lindy certainly absorbed the more formal European style, which she has used with her landscape design clients in San Anselmo, but now leans toward a more Asiatic, free-form, and contemplative style. Hours can go by on the clock and yet she remains completely engaged in painting or gardening. Her sense of time is gauged by the passing of light coming down the slope in her backyard on a diagonal. The light rays change from hour to hour, season to season, sunrise to sunset, through the tall tree trunks of cypress and pine that form sharp angled shadows in the fading light of dusk. The geometric shapes of the shadows provide structure in the garden, which she has planted with numerous specimens of plants and flowers that relate to the light on the hillside, probably the same way her mother did when Lindy was a child.

Reflections

“Is there a contemplation I have to put into the watercolor? I know the other painters’ contemplations rub off on me . . . there is nothing but complete focus, one-pointed focus, it’s like a meditation when I put the time aside to work on a drawing or painting. It’s no longer analytic, it’s creative. In the integration of music and my visual brain, I infuse my whole being into the process.”* There is always an element of mystery in the dynamic relationship between the painter and the painting. Lindy sometimes seeks to paint in rhythmic phrases, with appoggiaturas (grace notes performed before a note of the melody, falling on the beat), leaving emphatic brushstrokes, like musical notes made apparent. She paints to Mozart in particular, for his sublime, rhythmic patterns. She claims to hear tones and see pigment colors simultaneously, which is a new phenomenon for her brain.

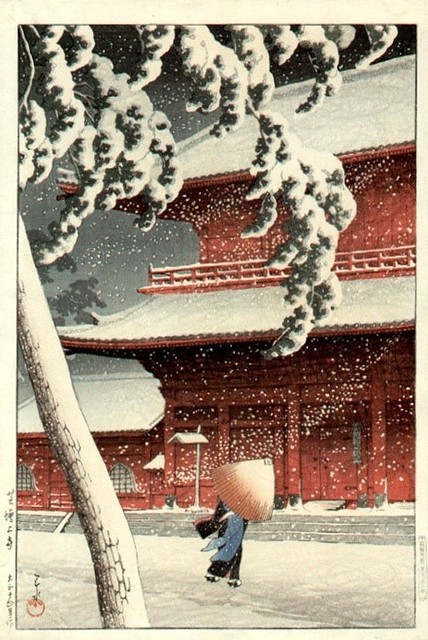

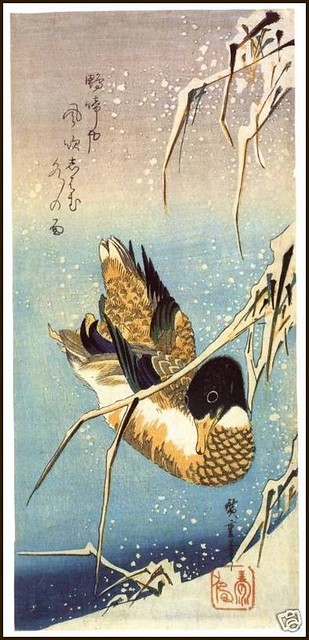

Hasui Kawase (1883–1957), who worked in the early 19th century, has been one of her all-time favorite Japanese block print artists. Andō Hiroshige is another favorite. His print, Wild Duck Swimming, is a beloved Japanese print she acquired in recent years. What drew her to the Japanese block print form of art were the asymmetry and clarity of design, the complexity of image and color, and the exciting presentation of the natural world, especially of snow, rain, and trees!

century

Garden meditations

Lindy bases her drawing and painting on the myriad ways in which she interacts with the natural world. These are her everyday meditations. In the garden, she spends many hours planting seedlings, bulbs, and seeds, in addition to fertilizing, moving mulch, trimming shrubs, removing pests, and watering her plants. She saves seeds and dries flowers. Her husband, Heinz, a consummate potato grower, also enjoys working in their shared garden. Tending to and nurturing the natural world is a meditation in itself—the divine symbiosis of plant, animal, and humankind. To provide foodstuffs for the bees, butterflies, birds, moths, hummingbirds, and their own kitchen, Lindy anticipates the organic growth of edibles and blooms she plants, feeling excited for the beauty of tomorrow.

Photographic images of the forms, fruits, and shapes of her garden offer subject matter for her artwork. Moving her body and limbs among the branches of the trees and in the fertile soil, feeling the textures of both earth and leaf, which are stretching out toward the sun, bring simple pleasures. She delights in the effects that of light on the appearance of coloration in a plant, with the light source moving first into sunlight, then into shade on stems and leaves. The pigments seem to be the same but the eye registers further nuances of tone and value. The flowing variations of color, the scents of vegetation, and the branches moving gently with the breezes, seem brimming with promise. Nature’s cycles inform the mind’s willingness to open, receive, and render the glory of her mysteries into form.

* Personal interview, 25 November 2017

See more

Black Cat Studio and The Mary L. Harden School of Botanical Illustration