Imagine there is only one African rhino left in the world. It’s not hard to picture a scenario in which this lonely survivor of human greed is being pursued by poachers to the ends of the earth. As it is cornered on the African plains, its death heralding total obliteration of the species, wildlife activists block the hunting party in a desperate bid to save its life. “Kill this one and there will be none left,” the activists shout at the hunters.

They thought the hunters ignorant of the ramifications of their actions. They thought wrong. The poachers bawl back gleefully: “That’s the whole point!”

Counterintuitive as it might be—surely even the hunters need a hunted—there is a vicious logic to this suicidal spiral into extinction.

A perverse and vile scenario

It would be hard to think of a more sociopathic or greedy response to the concerns of ecologists, and in this scenario we are speaking only of endangered species. The global biosphere is already in dire straits. Some 53 per cent of the world’s fisheries are fully exploited, and 32 per cent are overexploited, depleted, or recovering from depletion, according to WWF data. Bluefin tuna and other once-commonplace species are on the verge of being wiped out. No country in Southeast Asia has a tradition of effective biological conservation, which allows illegal trafficking of animal parts to put immense pressure on a diverse array of species. The battle against the illegal trade in wildlife is a war on a scale far bigger than most imagine.

One would think that even the most avaricious of poachers or perpetuators of the slaughter of endangered species could see, from a position of pure self-interest, the benefit in preserving the species they hunt. Extinction surely means a loss of livelihood. Yet, terrifyingly, vested interests have a lucrative reason to hope that these species should disappear forever, for the consequent increase in the value of the products farmed from those species would be high enough to last a lifetime. The influential marine wildlife environmentalist Paul Watson called this the “economics of extinction.”

The mechanism is relatively straightforward. To use a recognizable example, demand for African elephant tusks is wiping out these magnificent, emotive creatures. The poached tusks are stockpiled off the market, and as the elephant population plummets the value of those tusks soars. There is no incentive to stop the elephants from being wiped out because the tusks that remain will accrue astronomical value. It is highly likely that other products, such as body parts from sharks, rhinos, primates, and other creatures are subject to similar demand.

The only way to defeat supply is to discourage demand. While it is commendable to arrest poachers and to police wildlife reserves, campaigns to frame the wildlife trade as barbaric and uncivilized in the public consciousness do much better at reducing demand for products emerging from that trade. The campaign against shark fin soup consumption is a good example. In a 2014 report, wildlife trade concern group WildAid observed that sales at shark fin vendors had collapsed 82 per cent, and Chinese basketball superstar Yao Ming’s advocacy contributed to this significant decline in shark fin consumption in 19 out of 20 Beijing restaurants surveyed. (WildAid)

Moral authority and paradigm shifts

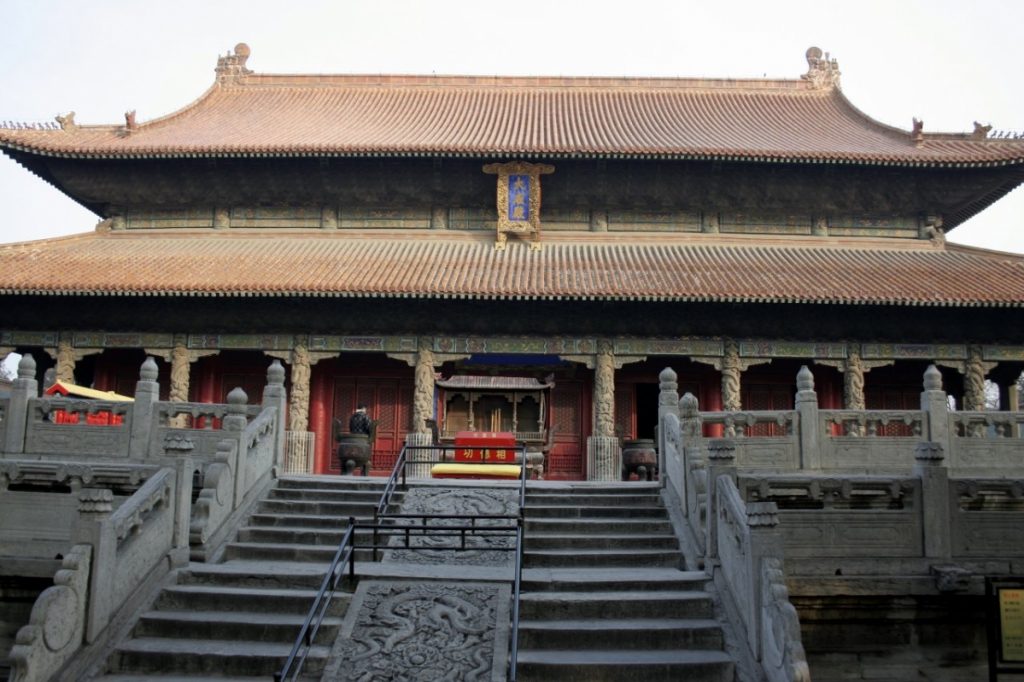

As one of the largest markets for endangered species, China has drawn criticism for the trafficking in the body parts of endangered species, which are often used as ingredients in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). The country’s great spiritual and ethical traditions of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism, all of which have played critical roles in the foundation of Chinese civilization, have recognized that without their involvement and spiritual injunctions against the wildlife trade, ecological biodiversity across the world will likely decline further from the economics of extinction.

Huge credit should be given to the China Daoist Association (中国道教协会). In 2003, the association published an authoritative statement that noted: “People should take into full consideration the limits of nature’s sustaining power, so that when they pursue their own development, they have a correct standard of success. If anything runs counter to the harmony and balance of nature, even if it is of great immediate interest and profit, people should restrain themselves from doing it, so as to prevent nature’s punishment.” (Alliance of Religions and Conservation)

Accordingly, the association also urged: “When [TCM] endangers the natural world it is no longer in alignment with Daoism’s spiritual principles. . . . There is no need to use expensive or rare ingredients from endangered species such as tiger bone or rhino horn. Daoism shows us that there are many ways to cure any one illness, and prescriptions that include animal ingredients are not necessary. Let us respect and inherit these Daoist traditions, and develop TCM in ways that benefit both human and non-human life. We ask all suppliers, practitioners, and consumers of traditional medicines to protect and care for plants, insects, and other creatures, especially endangered animals, and to refrain using them in TCM. (Alliance of Religions and Conservation)

In 2013, the theologian Martin Palmer reported that Chinese Confucianists had begun working on an eight-year plan of environmental action based around their many academies and temples. The various Confucian and Daoist initiatives, wrote Palmer, demonstrated a desire to find ways of being and living that “reflect deep Chinese cultural traditions.” Daoism and Confucianism, he declared, “as the two indigenous spiritual and philosophical traditions of China, are at the very core of the recovery of a specifically Chinese perspective on protecting our planet.” (chinadialogue)

Chinese Mahayana Buddhism, a foreign-turned-native tradition, is also in a strong position to join this beneficial resurgence of cultural values. Buddhist institutions should reach out to Confucian academies and Daoist temples to see how they could work on environmental projects together. Buddhist temples can host seminars and programs on the importance of wildlife conservation and the horrors of animal trafficking. These creatures are our fellow sentient beings, and we should not be treating Buddhas-to-be so appallingly.

While the act of consuming products from wildlife trafficking might be mistakenly perceived in some circles as a badge of taste or affluence, such behavior actually impoverishes the world’s affluence by driving species to extinction. We are only truly affluent when all life in the universe is allowed to flourish. The less biodiversity there is, the more impoverished we become. This is a spiritual injunction that also has ramifications for national development and the environment, which should concern the government.

The reality is that the traditions of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism teach ways of being that are far truer to the Chinese spirit than the materialist rapaciousness of wildlife trafficking. The environmental movement cannot (and should not) rely on instilling guilt or fear in people, which is often counterproductive.

China’s spiritual traditions should unite around the shared narrative that our inner and outer flourishing cannot happen if the destructive and wanton consumerism of wildlife is prioritized. The positive richness of nature is an affirmation not only of the planet’s ecological health, but also of the interconnectedness of all phenomena as taught in Buddhism, the natural way of the cosmos as seen in Daoism, and the Confucian sense of duty to one’s community and the need to cultivate the better nature and aspects of society.

The planet has never faced greater peril from the economics of extinction. Yet Chinese Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism have never been better placed to guide Chinese society toward a truly beautiful vision of Earth’s future.

Back to Planetary Healing: Buddhism and World Ecology Special Issue 2017

See more

Unsustainable fishing (WWF)

The Politics of Extinction (Truthdig)

Evidence of Declines in Shark Fin Demand, China (WildAid)

Daoism, Confucianism and the environment (chinadialogue)

Daoist Faith Statement (Alliance of Religions and Conservation)

Daoism Wildlife Statement (Alliance of Religions and Conservation)