Sky dancers people the higher dimensions of Buddhist art and metaphysical symbolism. They go by different names: apsara, feitian, ging, dakini, khandum, yogini, and indeed each of these sky-dancing creatures is distinct; these are not merely different names for the same thing. What they share is their angelic nature, their rarified consciousness, and otherworldly beauty. Defying gravity and the constraints of time and space, they are extraordinary dancers. In fact, if you ever see a flying sky dancer, you are probably in another realm, or on your way to one.

Japanese classical culture often reached sublime heights of artistic expression by taking a known story, a Chinese myth, an imported trope, and making it quintessentially Japanese by means of artistic method and spiritual focus. The classical arts of Japan nearly always include not only a religious justification for techniques and approaches to the subject matter, but indeed a religious action, an embodiment of metaphysical principle.

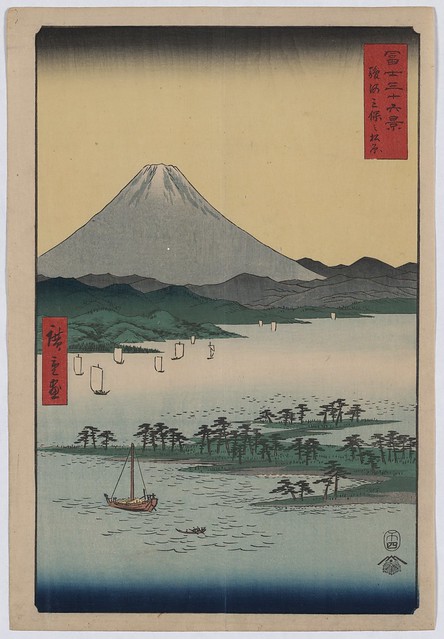

Period. Unknown artist depicting Miho no Matsubara, the

shoreline at the base of Mt. Fuji

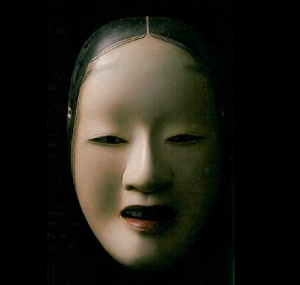

The Japanese Noh theater, appearing in the 13th century as sarugaku, led by its foremost performing and writing exponent, Kan’ami, become Nohgaku in the hands of his genius son Zeami. Noh became a literary treasure house, and a multi-art form combining architecture, drama, poetry, music, masks, costumes, and dance. Each art form is in an archaic and essential form. These are held together as a whole by energy and silence. The dance in Noh is abstracted and one of pure forms, like the universe framing dimensions of complete possibility.

Zeami taught as a powerful secret of his school of Noh, that the dance of Noh would be modeled on the Suruga-mai, or dances of the heavenly maidens when they appeared on Udo Beach. They revealed an otherworldly grace, a transforming power, and an inspiration to believers here on Earth. They moved between dimensions and dance was how they did so.

In the Noh play Hagoromo (The Feather Robe), we see one of the most beloved and common Noh plays, exemplifying what Zeami called the essence of Noh: “to unite high and low, and bring joy to the hearts of the people.” Here, a tennin, or heavenly creature, a sky dancer, loses her feather robe while swimming at Miho’s Matsubara Beach. A lowly fisherman takes it unknowingly, and only agrees to return it, allowing her to return to heaven, after she consents to perform a celestial dance for him.

The role of sky dancers in Buddhist metaphysics, in teaching and demonstrating dances, is remarkable and quite unlike other religions. It is the yoginis Yeshe Tsogyal, Mandarava, and Goma Devi who directly instruct yogis in Cham and Dzogchen dances. Dancing khandum instruct the dying person to make the right choice for avoiding rebirth in The Book of the Dead. Ging and dakinis fly around Zangdokpalri’s rainbows as part of the tantric dance generator it is.

Hagoromo is a most Japanese, sweet, distilled version of the story of a sky dancer demonstrating a dance. She wears a phoenix, the symbol of eternal rebirth, on her head. It is the source of her feathered robe. She performs the perfect heavenly dance for the fisherman, in gratitude and grace, and as a partner in the timing of the universe. She establishes the truth of the dances of Noh.

1940. Divine and cosmic power

It was the Zen aesthetic that Zeami incorporated with the Mahayana redemption, aspiring to escape the Wheel of Life and Death. The deft touché of awareness is what Zen trades in, and far from the tall tales of flying dancers and yogic visions, is the pure presence of the divine creature bathing the fisherman in light. It is the invisible calligraphy that the angel writes in the air. This is a silent shared moment between dancer, actor, and audience. All are held in the vital present. Energy, not form, vibrates from the performer. Consciousness is lifted as the main actor, the sky dancer, lifts his own. This is the blossoming moment, the “flower” of Noh, the transcendent understanding of the beauty and transience of life. The perfected forms of Noh become skilful means for experiencing higher consciousness through the appreciation and practice of art.

Remarkably, in the figure of one of the great ballerinas of our times, Wendy Whelan, for many years principal dancer of the New York City Ballet, not only the story, but the indelible presence of Hagoromo comes alive again. Whelan plays the angel in this production conceived by David Michalek. The fisherman is played by legendary New York City Ballet dancer Jock Soto. These two have been among the great partnerships at the NYCB over the decades, and seeing them rejoined in Hagoromo lends to the portrayal of a natural, spiritual wisdom; the dance of realized beings.

The angel dances for the fisherman. Photo by Stephen Kornbluth

CHORUS:

In white dress, black dress

Thrice ten angels

In two ranks divided,

Thrice five for the waning,

Thrice five for nights of the waxing moon,

One heavenly lady on each night of the moon

Does service and fulfills

Her ritual task assigned.

ANGEL:

I am one of their number,

A Moon-lady of Heaven.

(Hagoromo, translated by Arthur Waley, 1921)

See more