I met Ricardo Guerrero in July last year, during a landmark conference between Buddhists and Carmelites in Avila, Spain. It was an unusual conference by any standards: few Buddhists have much knowledge of Saint Teresa’s Carmelite Order, and Spain has had relatively little exposure to Buddhism. The conference’s premises and ambitions—to engage in genuine, non-missionary interfaith dialogue in the globalized age of Pope Francis—requires deeply original thinking. But Ricardo, a Spanish-speaking Buddhist leader immersed in Hispanic Christian society, is no stranger to original thinking.

Ricardo believes that he has always seen life in a Buddhist way. Born in 1964 and growing up Catholic, like so many children in Spain, he couldn’t find satisfactory answers to his questions about theism. “Many people in Spain see Catholicism as very close to power. The Spanish Church was complicit with the Fascist regime until 1979 and collapsed after Franco’s death. For us, the Church is historically compromised.”

The statistics seem to match: in Spain, fewer than 50 per cent of people profess to be Catholics, while only 18 per cent consider themselves practicing Catholics. This is a drastic decrease in numbers for a country that, only several centuries ago, was exporting Catholicism around the world through colonialism and helping to reshape the entire continent of Latin America in Catholicism’s spiritual image.

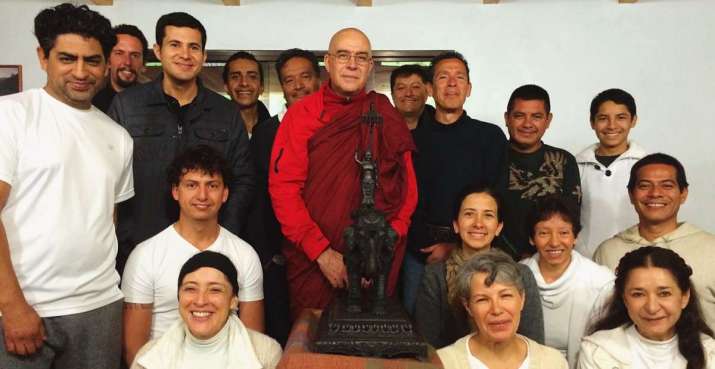

As for Ricardo, he left the Church at 18. In 2000, he went to Sri Lanka where he met the monk who would become his master, Ven. Nandisena—an Argentinian-born monastic who ordained in 1991 at Taungpulu Kaba Aye Monastery, in Boulder Creek, California, under Ven. Silananda. It was also Ricardo’s first time in a Buddhist-majority society, and he found the atmosphere of Colombo more welcoming than that of Madrid (he remembers, in particular, the many smiles of strangers). After reading about the Buddhist tradition and becoming a practitioner, he grew confident that it was the right spiritual path for him.

Together with Ven. Nandisena, Ricardo founded the Asociacion Hispana de Buddhismo (Hispanic Association of Buddhism) in 2012, with the goal of spreading Buddhism in South America. With the majority of the Spanish-speaking population living in South America, Ricardo chose to use the word “Hispanic” for his organization, rather than simply “Spanish,” taking into account the entire Hispanic cultural family. Notably, the Buddhist presence in South America dates back to the early 1900s and is actually older than the Buddhist diffusion in Spain, which really only began, very modestly, after the end of the Franco regime.

Expressly non-sectarian and ecumenical, the focus of the organization is to translate the Pali Canon into Spanish, although texts from different masters have also been translated. The association also offers meditation courses, classes on Buddhist thought (up to 40 sessions per year), and teaches mindfulness within the Buddhist philosophical framework.

“Publishing and translating is our priority. I’ve translated the work of Bhikkhu Bodhi, Ven. Dhammasami, and Shi Da Yuan. Without translated material we can hold and read, we have no hope of spreading Buddhism,” said Ricardo, explaining that the Pali Canon is absolutely crucial for Hispanic people to gain a solid, foundational understanding of Buddhism’s earliest teachings.

Ricardo draws inspiration from the US, as a model for the introduction of Buddhism in a new society. Buddhism in America, he explains, has been introduced at a relatively large scale, including diverse Buddhist traditions. It was the epicenter of what would come to be known as “Western Buddhism”—a distinct spirit if not a de facto new vehicle of Buddhism repackaged for American culture, concerns, and priorities. He feels that Hispanics need to move toward something similar: “We lack texts in Spanish and texts by Hispanic Buddhist scholars. Spain never had a true relationship with Asia outside of the Philippines, so it’s extremely difficult to acquire Spanish resources.”

The association has a base in Madrid and interested parties are welcome to visit the center. “There is already a solid Buddhist community in Madrid,” Ricardo notes. “But many Hispanic people are approaching Buddhism for answers they cannot find in Catholicism.” In 2011, Ven. Nandisena helped to establish the Instituto de Estudios Buddhistas Hispano (Hispanic Institute of Buddhist Studies), which operates under the association. It offers a diploma in Buddhist studies, which can be obtained by following an online course.

Despite the assocation’s many achievements, progress is gradual and often slow. It also hasn’t entirely been smooth sailing. Ricardo had wanted to establish a temple in Madrid with the help of the city’s 180,000-strong Chinese community. Unfortunately, he was unable to gather the sufficient funds and had to let go of the idea. He also concedes that his views on establishing a uniquely, culturally Hispanic temple does not always align with the aesthetics or preferences of potential collaborators, many of whom hail from an Asian context or heritage. “We don’t wish to open some kind of ‘ethnic’ temple that is commonly seen in other cities—while we welcome different cultural communities to open their own temples, we need a truly acculturated Buddhist center that is to Hispanic tastes and not simply importing Asian expressions.”

Ricardo is not shy about listing the trials ahead. Buddhism always needs time and patience to grow in a society acclimatized to a different religious tradition. Whether we speak of the “Old World” of Spain or the “New World” of Latin America, Ricardo feels that through its ancient teachings of meditation and comprehensive ethical guidelines, Buddhism provides desperately needed alternatives to the crisis of human values in Hispanic societies today.

“The traditional answers don’t work, and many are trying to find something they don’t know actually exists and is available for them,” he said. “We’ve suffered a lot through economic and social crises. Buddhism can support the individual. But, even though Buddhism is a personal practice, it needs communal support. One can’t do without the other. That is what this association is for.”

See more