The origins of “Pure Land Buddhism,” or more precisely, “the Buddhism of Pure Lands,” can be traced to the developmental stages of the Mahayana tradition. It bears both Indian and foreign religious elements acquired in the cosmopolitan milieu of northwest India. Along with the general Mahayana proliferation of Buddhas and cosmic bodhisattvas, we observe the belief in many Buddha-fields or Pure Lands—ideal places of unworldly purity that represent the journey of bodhisattvas to an enlightened state. Arguably, in the 2,500-year-long history of Buddhism in Asia the most popular of all Buddha-fields is Sukhavati, the blissful abode of the Buddha Amitabha, whose name means “immeasurable light.” His veneration is noted in China, Tibet, Korea, and especially in Japan, where it boasts the largest population of Buddhist followers.

The 13th-century colossal statue of Amida at the temple Kotoku-in in Kamakura stands witness to the devotion of the Japanese in the Mahayana tradition that came to be known in scholarly and partisan circles as “Pure Land Buddhism.” Buddhist pilgrims and tourists alike visit Kamakura to behold this 13.35-meter bronze statue of Amitabha, whose worship was systematized into an intricate theology by two famous teachers associated with the formation of Japanese Pure Land that dominated the Kamakura period of Buddhism, Honen (1133–1212) and his student Shinran (1173–1263).

Chinese Buddhism features a long and rich history of Pure Land developments and innovations with the early contributions of the illustrious masters Tanluan (476–542), Dao Chuo (562–645), and his student Shandao (613–81). Mural depictions of the Buddha Amitabha and his Pure Land, Sukhavati, at the Mogao caves in the Tarim Basin attest to his supplication both among Chinese residents and Tibetans, who governed the oasis town of Dunhuang at different times during the Tang dynasty (618–907).

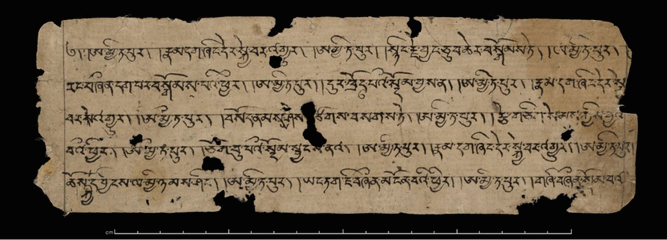

By the 8th century, the doctrines and practices of Indian and Central Asian Pure Land Buddhist traditions had reached the Tibetans, who embraced them and in time, produced their own indigenous Pure Land scriptures (Halkias 2013, 66–83). The Tibetan Buddhist canon features translations of two seminal texts in East Asian Pure Land Buddhism, the short and long Sukhavativyuha sutras, and twelve more Indian Sanskrit Mahayana and Vajrayana compositions that include five short dharaṇi texts (mystical incantations) invoking the presence and qualities of the Buddha Amitabha and his western Pure Land.

The Tibetan worship of Amitabha continued well beyond imperial times (7th–9th century), and over the centuries, gave birth to a unique genre of Tibetan Pure Land Buddhist literature. The demön genre comprises long and short aspiration prayers for birth in Sukhavati, elaborate lamrim- (gradual training) style commentaries, mortuary rituals, and contemplative practices inspired by the sutra and tantra traditions. Tibetan sutra and tantra teachings complement each other and are intended to embody a complete path of spiritual training towards Buddhism’s highest goal, the gradual realization of the enlightened state.

Many prominent Buddhist scholar-adepts from the Geluk, Kagyu, Nyingma, and Sakya schools of Tibetan Buddhism composed compelling aspiration prayers and gave elaborate teachings on the merits of Sukhavati. Unanimously quoted by Tibetan Buddhist masters from all schools, this important passage from the long Sukhavativyuha Sutra describes four practices that ensure rebirth in the Pure Land after death:

“O Ananda, any sentient being who recollects the Tathagata [Buddha] and his aspects, generates immeasurable roots of virtue, fosters the mind of enlightenment, completely dedicates [his merits for that cause], and prays to be born in the Land [of Bliss], when the time of death nears will face the Tathagata, Arhat, Perfectly Enlightened Amitabha, surrounded by a gathering of monks” (Peking Kangyur, vol. 22, 5.9.119).

In the Tibetan translation of the sutra, it corresponds to the 19th vow the bodhisattva Dharmakara pledged before attaining enlightenment in the form-body of Amitabha. Therefore, a Pure Land practitioner who aspires to attain rebirth in the Pure Land—a place of ultimate refuge arising in dependence on her aspiration and the fulfillment of Dharmakara’s vows—should engage in the following four activities: a) recollect Amitabha and his enlightened qualities; b) accumulate merit through virtuous activities of body, speech, and mind; c) foster the aspiration to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all forms of sentience; and d) dedicate all meritorious activities for rebirth in the Pure Land envisioned by Dharmakara.

Vajrayana Pure Land teachings are further geared towards the recognition of our luminous state of mind relying on the support of sound, visualization, and symbolic referents like maṇḍalas. Following the dissolution of the five aggregates of individuality into emptiness one arises in the form-body of the central deity, which in this case may be the Buddha Amitabha/Amitayus or the bodhisattva of compassion Avalokiteshvara, the regent of the Pure Land. In Vajrayana Buddhism, the characteristic bliss of Sukhavati is realized in this very life with proper training and the guidance of a qualified teacher.

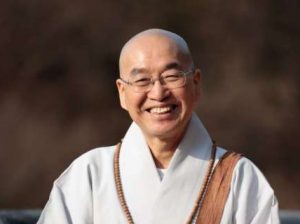

The tantric technique of transferring one’s subtle consciousness to Sukhavati is also important among Tibetan Pure Land practitioners. Many lamas and lay practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism practice the technique of phowa, which can be performed either for oneself or on behalf of the recently deceased.* This method is said to effect the transference of one’s very subtle mind to the Pure Land of the Buddha Amitabha so that the bardos, here referring to the intermediate states between death and rebirth, are bypassed entirely.

In Tibetan Buddhism, the Buddha Amitabha manifests in sambhogakaya ornamentation as the Buddha Amitayus, meaning “immeasurable life.” Although there are different artistic conventions and ritual practices associated with them, they are in essence the same Buddha with two aspects. The Buddha Amitayus is invoked during tantric rituals for long life, and figures as one of the most important long-life deities in Tibetan traditions.

For more than a millennium, the Buddha Amitabha/Amitayus and his Land of Bliss have been celebrated in lay and monastic Tibetan religious life and art. They feature in a stunning variety of ritual and contemplative Tibetan texts. The Pure Land teachings do not belong to any particular Tibetan Buddhist school, nor do they constitute an independent tradition; they have been interpreted from the perspectives of the sutra, the tantra, and the teachings of the “Great Perfection” (Dzogchen). The identification of Sukhavati with the “nature of the mind” prompted the well-known scholar and Nyingma master Dudjom Yeshe Dorje (1904–88) to proclaim that “the entire world of appearances and possibilities is the field of Sukhavati” (Halkias 2013, 187), and the siddha and treasure-discoverer (tertön) Namchö Migyur Dorje (1645–67) to reveal in a “pure vision treasure” (daknang terma) that we ought to “meditate on all places as Sukhavati” (Halkias 2013, 175). Therefore, in Tibetan religious contexts Sukhavati served not only as a tangible expression and attractive vision of what lies beyond death, but as a description of an enlightening vision that we can attain gradually, or non-gradually, in this lifetime.

*The Tibetan Buddhist master HE Choeje Ayang Rinpoche is considered the foremost authority on the phowa teachings and Tibetan Pure Land Buddhism. For more information, see HE Choeje Ayang Rinpoche.

References

Halkias, Georgios T. 2013. Luminous Bliss: a Religious History of Pure Land Literature in Tibet. With an Annotated Translation and Critical Analysis of the Orgyen-ling golden short Sukhavativyuha-sutra. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Hearn, Lafcadio. 1897. Gleanings in Buddha-Fields: Studies of Hand and Soul in the Far East. London: Kegan Paul.

Unless otherwise stated, all photographs are by the author.