First, 72 labors brought us this food; we should know how it comes to us.

– Zen oryoki chant

Second, as we receive this offering, we should consider

whether our virtue and practice deserve it.

Third, as we desire the natural order of mind, to be free from clinging

we must be free from greed.

Fourth, to support our life, we take this food.

Fifth, to attain our Way we take this food.

Whenever I’m struggling with asking for some kind of help, I often think of the Zen practice of oryoki. While it’s been a while since I’ve been part of a retreat where oryoki takes place, the ritual is still deeply embedded in my body.

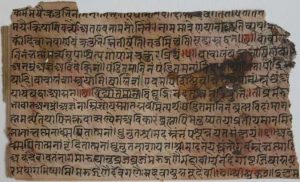

During longer retreats, called sesshins, Zen practitioners eat our meals inside the zendo (meditation hall) in a practice called oryoki, derived from a Japanese word that means “just enough.” It’s a beautiful and intricate ceremony with very specific protocols for how one receives the food being offered. If you and I ever have a chance to meet in person, ask me about my first encounter with oryoki at the San Francisco Zen Center. It’s worthy of a wacky Marx Brothers movie.

In an oryoki ceremony, servers kneel in front of each person and carefully ladle rice, soup, or whatever might be in their container into one of the three bowls of the meditator. Once everyone has been served, meditators are invited to consider the source of these foods and offer gratitude in the form of a humble bow.

Throughout the ceremony there are various chants. One comes after we meticulously set out our three bowls and utensils on our cloths:

Now we set out Buddha’s bowls;

may we, with all beings,

realize the emptiness of the three wheels:

giver, receiver, and gift.

The main point of oryoki practice, as I understand it, is to realize that “giver, receiver, and gift” are inseparable. As we engage in this practice we begin to learn how to give from a full heart, without attachment, and how to receive with grace and gratitude.

Taking part in oryoki meals over the years has taught me a lot about understanding giving and receiving in a non-transactional way. In everyday life, we often give something with an expectation that we’ll get something back, whether that’s a material object, prestige, respect, or even love. This kind of quid pro quo can feel forced and awkward—and it’s exhausting. It is one of the reasons many of us avoid asking for help.

We have gotten conditioned to thinking of giving and receiving as being an ego-driven act, but what if we look at it in another way? If we understand that we live in an interdependent world, to use Thich Nhat Hanh’s phrase, we see how we need each other to survive and thrive. We offer people a gift when we invite them to help us—in a genuine way that is based on relationship rather than transaction.

Think about a time when you gave something to an individual or group and it felt really great. You actually couldn’t wait to offer your money, time, or expertise. What was it that made the difference? Why did that act of giving feel like a joy rather than an obligation or imposition?

My guess is that first of all you felt some kind of affinity with the person doing the asking—even if you didn’t know them well. Maybe they reminded you of a younger version of yourself. Or perhaps they were asking on behalf of a cause that you are deeply committed to, such as environmental justice. Second, that act of giving connected you with the asker in an intimate way, and we live in a society that is starved for true intimacy. Finally, your own joy may have increased as you saw the recipient of your gift be able to do something they couldn’t do without this assistance. This relationship between giving and receiving is a very tangible way that we can become aware of the economic privilege that might have accrued to us in part because of our social position, and leverage that privilege for the greater good.

I invite you to consider all this as you notice any resistance that may arise as you consider asking for some form of assistance. What if, in asking another person for help, we are actually offering a gift to them? How might this awareness change the way you enter into a request for assistance? It’s a powerful practice. Give it a try.

Finally, to take a deeper dive on this practice of giving and receiving, consider the three ways of giving that are outlined in traditional Buddhist teachings:

• Amisa-dana: Giving material aid and objects, particularly to those in need. Traditionally this took the form in Asian communities of showing up early in the morning to offer food to monks during their alms rounds. In current times, it might look like creating bags of warm clothes and toiletries for our unhoused relatives.

• Dhamma-dana: Giving “loving protection,” in the form of Dharma teachings and guidance. Dhamma-dana can also include offering skillful advice to anyone in our circle.

•Abhaya-dana: Giving the gift of non-fear, considered to be the greatest gift of all because it empowers the receiver to make choices from a place of confidence.

What do you have to give, and how can you do so from a non-dualistic mind? What do you need, and how can you receive it also from that same outlook? There is so much to be gained from exploring the act of giving and receiving from a Buddhist perspective. I look forward to hearing your experiences and insights with this in the comments.

Related features from BDG

On Relationships, Greed, and Generosity

Engaging the Six Paramitas to Care for Animals, Part One: Generosity, Discipline, and Patience

Buddhist Robes and Buddhist Sacraments

A Time of Giving: A Christmas Meditation on Generosity for Buddhists

Threads of Generosity — The Work of Artist Lee Mingwei

Dilemmas of Generosity

From Happy Meals to Metta Meals

I love this reframing of some of our assumptions: “We offer people a gift when we invite them to help us.” This matches some rethinking I have done lately in regards to reaching out to former students.

I had the opportunity to be a server in the oryoki practice at SFZC that Maia describes in her article. I approached this with great trepidation, aware of so many things that could go wrong, such as making too much noise on bringing in the food to the zendo, dropping the tray of food, spilling food as I ladled or spooned the food into people’s bowls, putting it into the wrong bowl…

But this came to be one of the most significant experiences of my life. As I moved through the stages, as I spooned food into a person’s bowl, I felt such open heart in each person, each one supporting me in my role. I thought I was giving and the food was the gift and then realised that I was receiving so much and that the gift was to be in this role that I had feared and the flow of love being given by the person receiving food from me. I realised no separation between giver, receiver and gift, true unity.