In union, primordial energies come to be: spiritual potentiality and

spatial reality. The potential becomes real; the spiritual becomes

spatial. Image courtesy of Musee Guime

This three-part series examines tantric deities in the yab-yum posture of symbolic sexual congress. But beyond the obvious, why are they dancing? Indeed, why dance? This is a fundamental question where there is a depiction of dance in religious art, more so in prescriptive meditation art. I wondered earnestly for years why Padmasambhava used dance as the first art of Tantric Buddhism, establishing Vajrayana Buddhism at Samye Monastery in Tibet. I marveled at its primacy. I sought the insight to make the connection with dance and the establishment of psychic energy. One day, I asked the Je Khenpo, the head lama, of Bhutan, “Why did Guru Rinpoche use dance as the first art of Tantric Buddhism?” He answered, “Because people like dancing.” Sometimes answers are simpler and more surprising than expected.

I was startled when I read that Italian explorer Giuseppe Tucci (1894–1984) described the coupled deities in a temple mural of tantric meditation cycles, as engaged in “an orgiastic dance.” Tucci was the most perceptive of adventurers, with an ability to extrapolate cultural traces toward speculation of the very ancient. He was a master of interpreting symbols. The diverse languages in which he could read and write—among them Chinese, Pali, Sanskrit, Tibetan, Persian, Hebrew, and Classical Greek—each used an entirely different set of symbols to represent the sounds that comprise spoken language. Beyond fluency, Tucci was satisfied only when he could experience the poetry of a language, extinct or extant.

Tucci brought the same finesse to the study of Buddhist religious art, meticulously identifying every figure in temple murals, and by the same means he also learned the vast interconnectedness of meditation teachings, which are symbolically represented by figures—what Tucci called “A Buddhist Olympus”—as well as written down and transmitted mouth to ear. He was fluent in symbols, and his particular observations on the symbol of deities in yab-yum are noteworthy.

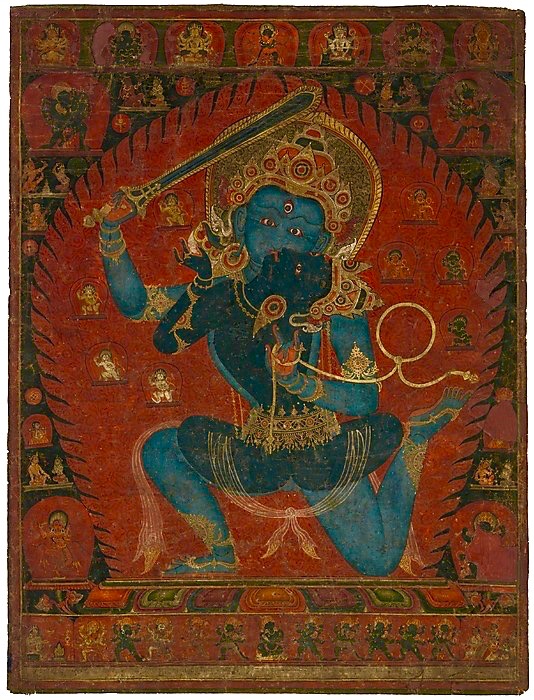

The direct power of the deity is strong in this tantric dance

Beyond archeology and linguistics, Tucci believed that knowledge of art and philosophy is essential to learning about a culture. He wanted to know what the symbols meant to those who produced them, down to a nuanced appreciation of cultural values. He used the word “orgiastic” several times in referring to deities in erotic embrace while dancing. After consulting with an Italian scholar, I confirmed that the Italian word and meaning was essentially the same as in English, connected to the Greek word orgia, “a gathering of several people who give free rein to their own instincts and sexual desires; from classical antiquity a ritual festival with norms of a Dionysian character; a mysterious rite.”

Orgia becomes a word with the emergence of Bacchic rites by the followers of Dionysius. Its origin is a religious superabundance. There was sex, slaughter, dismemberment, miracles in the natural world, dancing, chanting, and taboo transgression, all of it innocently in praise and honor of the god Dionysius. None of it was for its own sake, for the sake of pleasure, or the thrill of subversion. It might be worth noting that dismembered bodies float in the charnel grounds and hells depicted in the borders just underneath the deities in yab-yum about which Tucci writes so insightfully.

unknown. Note the very plain background. The arabesque of the

yogini’s body from toe to arm, the weight and sense of movement in

the deity’s lunging leg—these characterize dance. A delicate balance

is attained between sensuous realism and iconographic stylization.

From Core of Culture

Orgiastic is quite a term to use in describing a dance—particularly a dance of meditation deities. Tucci uses it when describing dancing wrathful deities in yab-yum in a mural painting at Tsaparang Temple in the Guge region of western Tibet. The words yab-yum mean father-mother, but in an expanded sense akin to the Chinese terms yin and yang, expressing complementary elemental energies. In the Tibetan conception, the male deity and his female consort are two aspects of the same single divinity; neither is superior. It is a transcendent symbol of the highest mystical union, Bliss and Emptiness, realizing the illusion of form. At the same time it is a depiction of sexual activity between athletic deities.

in harmonious movement and balance, the seed of each

within the other. Traditional. From Core of Culture

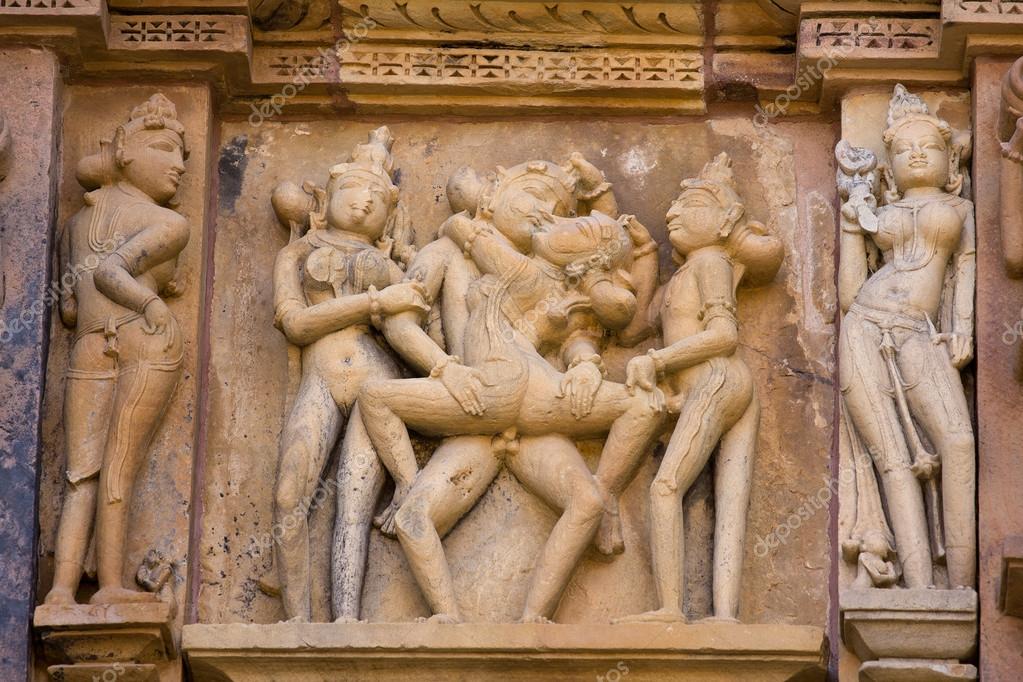

By contrast, the tai chi symbol representing the movement of yin and yang is not a depiction of sexual activity, although it is similarly meant to express fundamental ontological principles, including sexual coupling. Tucci emphasizes the visual connections to Indian art preceding their expression in Tibetan art. Ancient Indian sculpture and painting included a clear, if sacred, erotic energy between coupled deities. The eros is real, not merely symbolic, or less so, metaphoric. It was holy and it was sexually aroused.

Shiva, the Supreme Deity, is coexistent with the Void. In encountering his shakti, there arises the creation of the primordial energies giving life to everything; co-emergent, co-created. Even today, devout Hindus are sometimes bashful about the stone carvings depicting positions of the Kama Sutra that adorn temples. It is not symbolic sex to them. Tucci’s expert research methods transcended moralistic blindness and shock at the explicit. He was scientific and objective. Decades after first writing about tantric deities in yab-yum in Tibetan art, he would write one of his final books on erotically coupled tantric practitioners in Nepalese art, a subject more sexually extreme and varied than the one at hand.

Early 16th century, Nepal. Courtesy Himalayan Art Resources

Had the artists, or the yogis whose visions inspired them, wanted to eliminate the sexual aspect from the representation of cosmic principles, they would have designed something more like the tai chisymbol: no phallus, no yoni; lots of ontology. This art is overtly sexual for a reason. Enduring resonances of pre-historic indigenous ritual union? Actual tantric code “hidden openly” within mural paintings of tantra cycles, understood only by the sexually initiate? The ultimate metaphoric energies as literal beings in the mechanics of meditation? Elsewhere, Tucci suggests that the archaic Indian spiritual masters felt the deepest fundamental energies of life and sought, through symbolizing each in concrete form, to address them and turn them toward enlightenment and redemption.

This means that to depict them is to control them, to master them with dominant metaphysical principles. This does not preclude genuine eros in the depiction. In fact, the depiction of erotic union acknowledges the mystery of its archaic raw power. Buddhism absorbed the cultures and religions that preceded it; Buddhism did not annihilate them. Ancient beliefs, philosophies, and practices live on in Buddhism, transformed by its philosophy and metaphysics, while retaining the essence of their primordial identity and power.

The Gelugpa reformations effected to drain the blood and make abstract the occult from older Tibetan practices, systematizing them, and promoting a philosophical and metaphorical interpretation of sacrificial and erotic symbols, precisely because there were such entrenched practices and beliefs otherwise. To what extent is the eros real in Tibetan art? To whom? Why are Tibetan visualization deities dancing while coupled in erotic embrace? It is rather an outrageous idea. In an art in which nothing is left to chance, there is a reason they are dancing while conjoined in blissful union, producing an image of Bliss that is mind-blowing, all embracing.

“There remain, therefore, only the central figures on the wall to the right and to the left: a terrifying panel of coupled divinities who seem to be engaged in a gruesome dance. They are adorned with necklaces made of skulls and cut heads, brandish weapons, hold cups of skulls, and trample on creatures of more modest proportions who seem to contort under their mortal pressure.” (Tucci, 65)

has 16 arms and four legs; the dakini has two arms and two legs. Shining gold pierces

through the central column of energy chakras. The multiple arms can be seen as a

four-armed deity dancing. Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

References

Tucci, Giuseppe. 1935. Indo-Tibetica lll.2. Rome: Reale Accademia d’Italia

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Giuseppe Tucci, an Orgiastic Aha! Part One

Giuseppe Tucci, an Orgiastic Aha! Part Three

An Orgiastic Aha! Epilogue: Tucci in His Own Words