What do feeding monks, fighting a crowd to reach the front row of a rock concert, and celebrating the first day of summer have in common? They can all take place at a festival. Whether it’s a religious ceremony or an event in the name of art or music, festivals have a certain allure that brings together diverse crowds of people to share a cultural experience.

The anticipation of a major festival instills a certain type of feeling. There’s a welling of excitement in one’s chest, knowing that it is a “special day.” I have always been attracted to the type of energy that festivals generate. Being raised Catholic, the Christmas experience was filled with sensory delights signalling that it was an important time of year. Christmas music played over the radio, peppermint candies were sold, and an evergreen conifer tree appeared in the living room. A thrill came on Christmas morning from not knowing what to expect after a magical being’s personal visit to our home.

The out-of-time-and-place experience that came with the holiday festivities extend beyond the commercial side of the celebration. There was also the way the church was upgraded to honor the birth of Jesus with wreaths and the heavy scent of hundreds of flickering candles. But as maturity transpired, the level of excitement associated with Christmas began to fade.

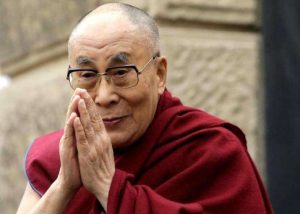

Even those in the United States who are not religious still tend to observe Christmas as a special time to spend with family or friends. Buddhists are familiar with religious holidays when they similarly celebrate important dates in the Buddhist calendar. The largest Buddhist celebration is known as Vesak, Visakha Puja, or Buddha Day. During Vesak, Buddhists across the globe celebrate the birth, enlightenment, and death of the Buddha.

Last year I attended a Buddha Day festival hosted at a Buddhist temple here in California. I went to the event alone, without knowing a single person there. It was my first opportunity to engage with the Buddhist community in Santa Barbara and I had no idea what to expect, aside from the fact that Buddhists know how to host a great celebration.

The first thing I noticed about the gathering was the beautifully wide variety of people that came to attend. There were many races and ages, and I immediately felt welcomed as a female college student. The day began with a traditional Theravada Visakha Puja ceremony, during which donations and food were offered to the monastic attendees. There was also chanting in Pali, Tibetan, and English. After a long lunch break, everyone gathered under the beautiful orange and yellow canopy that gave everything a relaxing glow, complimenting the colors of Thai, Tibetan, and Zen monks’ robes.

The second part of the celebration began with a recitation of the Buddha’s first teaching in Pali and in English. The visiting monks were then introduced, representing an impressive variety of monastic backgrounds. A substantial community discussion followed between those in the audience and the visiting monks on the relevance of the Buddha’s teachings in modern society.

In this way, Buddha Day served as a connecting force for a religion that began far away and has since made its way around the world. Americans who have no deep geographical connection to Buddhism had the opportunity to connect with monastics from the Asian regions where Buddhism originated. It proves how Buddhism is a religion that appeals to all, and has the potential to transcend cultural borders. Religious festivals show the importance of certain events in the religious year with certain rituals and festivals, reinforcing beliefs in them.* From Buddha Day, to Christmas, Yom Kippur, Diwali, and Ramadan, these festivities are relevant throughout the world.

When I traveled to Nepal, I quickly learned that there were more festivals celebrated than there are days in the year due to the diversity of religions, either of Hindu, Buddhist, or indigenous origins. In any diverse society, whether it be a variety of religious groups, immigrants, or a rank-based societal structure, festivals are able to take diversity and transform it into a common and transcendent identity. The magic also lies in that special feeling of not knowing what to expect, like a child on Christmas morning. This sense of the unexpected helped fuel the community discussion on Buddha Day on how things can be different than they are. It provided a significant opportunity for lay people and monastics alike to imagine how the binding values that brought them together could be imagined in our world today. It takes ancient religious beliefs to the future.

When I arrived at the airport in Ladakh, northern India, about a year ago, I was immediately greeted with a khata around my neck by Ladakhis in traditional dress and a schedule for the Ladakh Festival. I has not expected my visit to coincide with this annual celebration of Ladakhi culture, but as a foreign tourist I could not have asked for better timing. Throughout the week there were several traditional events, including dancing, singing, archery, polo, and cham dance. Many societies around the world have started to employ cultural festivals to attract tourists and boost their economies. In the process of image enhancement, these types of festivals also allow for cultural regeneration by reviving nearly-lost traditions and preserving local heritage. Beyond its capacity to inform tourists about the culture they are visiting, elders are able to share stories and experiences to unite generations to come.**

Humans are social by nature, so festivals and events become an opportunity to temporarily forget our fleeting, everyday concerns. They are unique experiences that allow for a deeper realm of connection by coming together over a shared common interest. Time and time again I feel something deep within me light up while at a festival. It’s that sensation that every human being craves—to feel united with one another.

The Summer Solstice Celebration is a festival that I helped to plan and hold last year—a large community arts event on the weekend of the first day of summer in an ocean-side community. Across all ages, religions, and political backgrounds, nearly 100,000 people gathered for a large parade and festival to honor the beginning of the best season of the year when you live near the ocean in Santa Barbara. What I witnessed, from the months of preparation to the execution, was unlike anything else. I saw massive crowds of people dance for hours on end, make new friends or deepen previous bonds, and try something new. I played with children while dressed as a giant bird puppet. I felt my heart open and my mind expand to the power of letting go to come together.

Image courtesy of the author

Something about these experiences is enlightening. I believe it is because they provide a special chance to come together with people from different cultures to celebrate a collective purpose in unison. The sense of belonging for religious, social, or geographical groups allows for a shared belief to develop in imagining what can be achieved when we work together. During festivals, we can enjoy being playful by breaking away from our day-to-day routines even as adults.

Celebrating culture and pride can also help keep our spirits up in times of crisis. Festivals can provide a counter-narrative to an unsatisfactory status quo. Sometimes these events are not for celebration, but for meditation or reflection.

Growing up in California, I found myself at the center of many major festivals, such as the internationally-known music festival Coachella. As an avid festival-goer of all types myself, I started wondering about the cross-cultural relationships between festivals. What really sparked my interest was when I attended my first “transformational” or alternative gathering. These festivals feature music, alternative healing tutorials, talks about social justice issues, and group meditation sessions. At events like these, festival-goers who have never thought about a meditation practice in their life are encouraged to give it a try. By offering different activities in a festival setting, participants are more likely to step out of their comfort zone and try something new.

Festivals serve societal unity. The atmosphere of a festival serves the creation, preservation, and foundation of social solidarity. Festivals are unique because they aid unity in the midst of diversity. The diversity and unity element of reversal found in festivals that can transform people and take them from one place to another.

A festival—whether a special event or an annual holiday—has the capacity to open the human heart to creative experience and play. You are sure to walk away a different person and experience a shift from one place to another after attending any type of festival.

* Juergensmeyer, Mark & Roof, Wade Clark, eds. 2011. Encyclopedia of Global Religion. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

** Lyck, Lise, Long, Phil, & Grige, Allan Xenius, eds. 2012. Tourism, Festivals and Cultural Events in Times of Crisis. Copenhagen:Copenhagen Business School Publications.