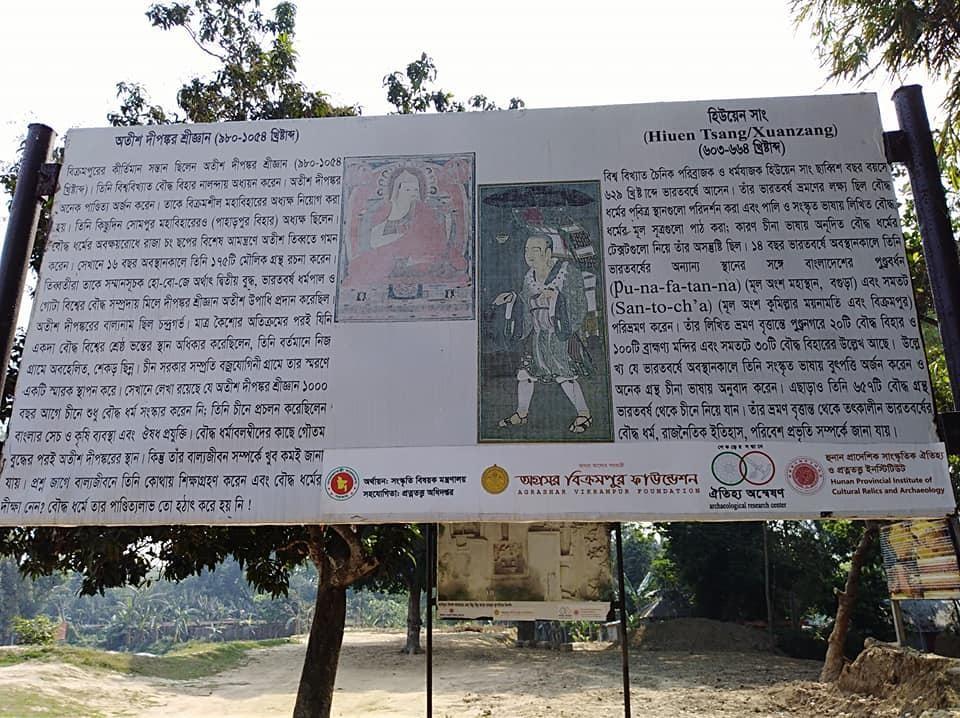

Atīśa Dīpaṃkaraśrījñāna (982–1054) was a Buddhist master who dedicated his life to compiling texts and propagating the Buddhist teaching for the benefit of all sentient beings from the territory of the old Indian kings to Indonesia and far beyond to the Himalayas. His texts, translations, and teachings were critical to the Second Diffusion of Tibet. Atīśa’s literary and scholarly works have impacted and enriched Buddhist traditions scripturally and doctrinally.

In 982 CE, Atīśa was born in the village of Vajrayoginī, Vikrampūra, in the district of Munshiganj of Dhaka, the capital of present-day Bangladesh. His royal name was Candragarbha—Moon Essence—given to him by his father, Kalyānaśri, and his mother, Padmaprabhā. Dīpaṃkaraśrījñāna was Candragarbha’s monastic name, bestowed by his preceptor, Ācariya Śīlarakṣita. He would receive his most famous name later in Tibet.

At an early age, Atīśa was influenced by renowned Indian masters such as Jetari, who first introduced him to the teachings of taking refuge in bodhicitta (the mind of awakening). There was also Vidyakokila, who taught him the essence of śūnyatā (emptiness). Eminent Buddhist teachers such as Rahulagupta, Avadhutipa, and Bodhivadra offered him additional guidance along his Buddhist path of awakening. As suggested by Rahulgupta, Atīśa decided to enter the monastic order. He was ordained as a monk under the supervision of Ācariya Śīlarakṣita.

After ordaining, Atīśa studied Buddhist philosophy, logic, epistemology, and ethics based on the monastic educational curriculum that defined the medieval super-monasteries such as Nālandā and Vikramaśīla. Then he made a pilgrimage to Bodh Gaya, the site of the historical Buddha’s enlightenment. It was sometime during this period that he decided to learn from a highly qualified master called Suvaraṇavīpa Dharmakīrtiśrī, who was also known as Serlingpa among Tibetans. Suvaraṇavīpa lived on the distant tropical island of Sumatra, which is now part of Indonesia. Atīśa made the journey by boat with a group of traders, taking more than 13 months to arrive. Under the compassionate mentoring of Suvaraṇavīpa, he spent 12 years learning and practicing the way of bodhicitta, which entails using various stanzas to guide one’s mind to be compassionate and mindful. Based on his studies under various Buddhist masters in Sumatra, Atīśa subsequently wrote The Seven Points of Mind Training.

Atīśa returned to his homeland after 12 years in Sumatra. His reputation as a brilliant Buddhist teacher rapidly spread throughout South and Southeast Asia. Honoring his extraordinary abilities and outstanding knowledge, the Bengal kings Mahīpāla (988-1038) and Nayapāla (1043-58) of the Pāla dynasty appointed Atīśa as the “high priest” (upadāya) of Vikramaśīla Mahārvihāra in present-day Bhagalpur in India’s Bihar State. Vikramaśīla was founded by King Dharmapāla (783–820) of the Pāla dynasty and was regarded as a sister university to the prestigious Nālandā.

Apart from his chancellorship at Vikramaśīla, Atīśa was further motivated to take up the position of abbot of Odantapurī (present-day Bihar Sharif, in Bihar) and Sompurī Mahārvihāra (Naogaon District of Rajshahi Division in Bangladesh), where he taught for 15 years. During his stay at Sompurī Mahārvihāra, Atīśa composed one of his masterpieces, Madhyamākaratnapradīpa.

Atīśa decided to leave Vikramaśīla after 17 years of teaching. After being invited by the Tibetan ruler Jangchub Ö, also known as Yeshe-Ö (984–1078), he began his long journey to the land of snows, arriving in Tibet in 1042. He had actually refused the invitation, but finally decided to go after reflecting on the sincere faith of Himalayan seekers of the Three Treasures: the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. Furthermore, Yeshe-Ö, a pious Buddhist, stressed to Atīśa that Tibet was only just emerging from its own dark age, after the period of the First Diffusion had collapsed following the death of Emperor Langdarma (d. 842), sending the Tibetan Empire spiralling into civil war. Tibet in the time of Yeshe-Ö was recovering, amid the Second Diffusion, but urgently needed to import Buddhist talent from elsewhere to re-establish the Dharma’s prominence.

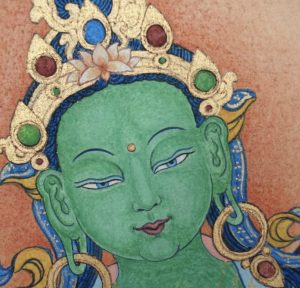

Having arrived in the Land of Snows, Atīśa was officially confirmed as a spiritual teacher by the Tibetan king, other Buddhist masters, and local devotees. He reintroduced and promulgated Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna teachings, worship of the five Tathāgatas (buddhas) in the Himalayas, and brought new Indian tantric concepts to the recovering Tibetan tradition. It was during this time that the king conferred on him the title of Atīśa, meaning “peace.”

In Tibet, Atīśa composed the monumental text Bodhipathapradīpa (A Lamp for the Path to Awakening), which describes three levels of spiritual capacity and establishes the foundation for the Lamrim teachings in 68 verses. The Bodhipathapradīpa had tremendous philosophical and doctrinal depth, and was later used by Himalayan masters as the basis for establishing the Lamrim tradition. Eminent Tibetan master Lama Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) consolidated and expanded his epic text Lam Rim Chen Mo on Atīśa’s Bodhipathapradīpa and Nāgārjūna’s Mulamadhyamakakārika. From Tshongkhapa’s Lam Rim Chen Mo, the reformist Gelug-pa tradition emerged in Tibet, influencing all the other Tibetan Buddhist schools, including the Nyingma, Sakya, and Kagyu.

The legacy of Atīśa and his teachings greatly impacted the next thousand years of Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna teachings. His importance has endured from India’s medieval Nālānda period to contemporary Vajrayana Buddhism, including the transmissions of acclaimed Tibetan gurus such as the Dalai Lama, the Karmapa, and Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Atīśa, who had been raised in Vajrayoginī and remains the national pride of Bangladesh, breathed his last in Tibet in 1054. Since the 10th century, his magnificent textual compilations and translations, have been of critical importance to Buddhist communities around the world. His Lam Rim Chen Mo is no doubt the most prominent body of his legacy. Although the fruits of his scholarship have been lost to his homeland, centuries of Buddhist civilization beyond South Asia have continued to inherit his contributions.

Atīśa transmitted the Buddha’s doctrine in a way unlike any other: he can be said to have saved Tibetan Buddhism, nurturing its weak flame as it was recovering from being nearly snuffed out. In the centuries since he died, his teachings have become legendary. Atīśa’s literary works have been passed down for hundreds of years to refine and spread Buddhist ideas to a broader audience, from the medieval period to today.

References

Behrendt, Kurt. 2014. Tibet and India: Buddhist Traditions and Transformations. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Chattopadhyaya, Aloka. 1996. Atiśa and Tibet. Delhi: Motilal Publishers.

Chowdhury, Sanjoy Barua. 2018. “The Legacy of Atiśa: A Reflection on Textual, Historical and Doctrinal Developments to Enrich Buddha Dhamma from the Azimuth of Vikramśilā to Modern Era” in JIABU: Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Universities (Vol. 11, No.1), Bangkok: Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University Press, 414–26.

Decleer, Hubert. 1997. “Atisa’s Journey to Tibet” in Religious of Tibet in Practice (ed. Donald Lopez). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Doboom Tulku and Glenn H. Mullim (trans.). 1983. Atisha and Buddhism in Tibet. New Delhi: Tibet House.

Tsongkhapa. 2004. The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Trans. Lamrim Chenmo Translation Committee). Vol. 1, New York: Snow Lion Publications.

Kalsang, Lama Thubten. (trans.) 1974. Atisha. Bangkok: The Social Science Association Press.

Related news from BDG

Bangladesh to Build Buddhist Monastery in Lumbini, Nepal

A Million Turn Out for Samyak Mahadan Buddhist Festival in Patan, Nepal

Archaeological Survey of India to Develop Vikramshila Buddhist University Archaeological Site