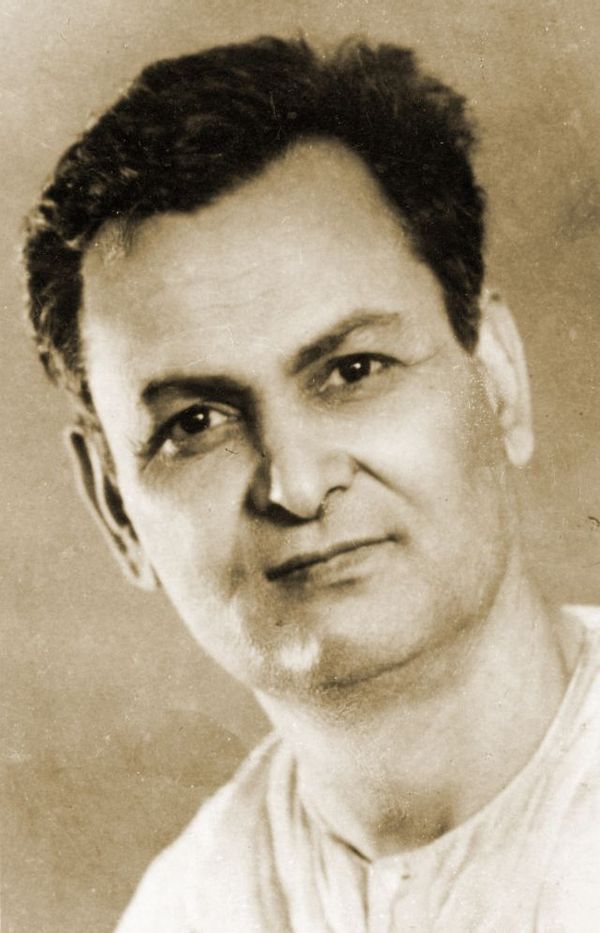

Rahul Sankrityayan (1893–1963) was a traveler and literary polymath who has been referred to as the “father of Hindi travel literature.” His interests were incredibly broad and it is difficult to fit him into any one box. While we will focus on his Buddhist side in this article, his seminal work was Volga Se Ganga (Volga to Gangas), a 1943 historical fiction collection of 20 short stories about the spread of Indo-European (referred to as Aryan) peoples into the Indian subcontinen, culminating in 1942. Like his life as an anti-colonial political activist and student of Marxismm, his Buddhist beliefs are not enough to define him. He was a translator and a student of world history. He enjoyed politics and art, and pursued religion with a distinct spiritual hunger. He was fluent in Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, English, Tibetan, Pali, Sanskrit, Arabic, and Persian. The Kashi Pandit community called him “Mahapandit” (great scholar) for his extraordinary erudition in Indian philosophy, especially Buddhist philosophy. As a result, he was known as Mahapandit Rahul Sankrityayan.

Sankrityayan was born in the house of his grandfather Ramsharan Pandey in the village of Pandaha, in the present-day Azamgarh District of Uttar Pradesh. As a child, he was known as Kedarnath Pandey. He lost his mother, Kulvanti Devi, early on. As a result, he spent his childhood under the tutelage of his grandfather. Ramsharan arranged for Kedarnath to study in a local Urdu madrasa, which was the only educational institution in the region.

Sankrityayan began to write from a very young age and his first publication was in Urdu. At first, the subject of his writing was travelogues because he was inspired by his grandfather’s service in the army and his visits to different parts of India. At the age of 10, he ran away from home to Kashi, but returned after a few days. Later, he moved to Calcutta and worked on the railways, and then in a shop as an accountant, where he learned English.

Sankrityayan built on his travelogue writing by going to different places and acquiring local knowledge. He concentrated on mastering the language wherever he went, paying special attention to Sanskrit, Pali, and Tibetan. He became proficient in all of these languages, as well as literature, philosophy, and rare books and paintings. He also became known as a skilled translator, having translated the Quran into Sanskrit.

Sankrityayan was very interested in maintaining contact with spiritual teachers. At the age of 18, he stayed at the monastery of Chakrapani Brahmachari in Varanasi and studied Dhrupadi, Sanskrit poetry, medicine, grammar, astronomy, and other subjects. At 19, he met Ram Avatar Sharma, a monk, and gained practical experience in various subjects in addition to his traditional studies. In 1915, he joined the Arch Musafir School in Agra and studied Sanskrit, Arabic, history, and theories of different religions for two years. It was here that his writings became widely disseminated, especially through essays in Musafir magazine in Agra and the Hindi magazine Bhaskar. In 1918, he traveled to Lahore and studied Sanskrit and Punjabi languages and literature. From this time onward he began writing many letters and diaries in Sanskrit.

Sankrityayan became actively involved in anti-colonial politics; he had already made a name for himself by criticizing the British government. The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre or Amritsar Massacre, in Punjab on 13 April 1919 transformed Sankrityayan into a powerful nationalist activist. He was arrested by the British government and sentenced to three years in prison for his involvement in anti-British activities. After his release, he moved to Bihar and joined Dr. Rajendra Prasad in further revolutionary activities. Later, he was inspired by the ideals of Mahatma Gandhi and joined his nonviolent resistance strategy.

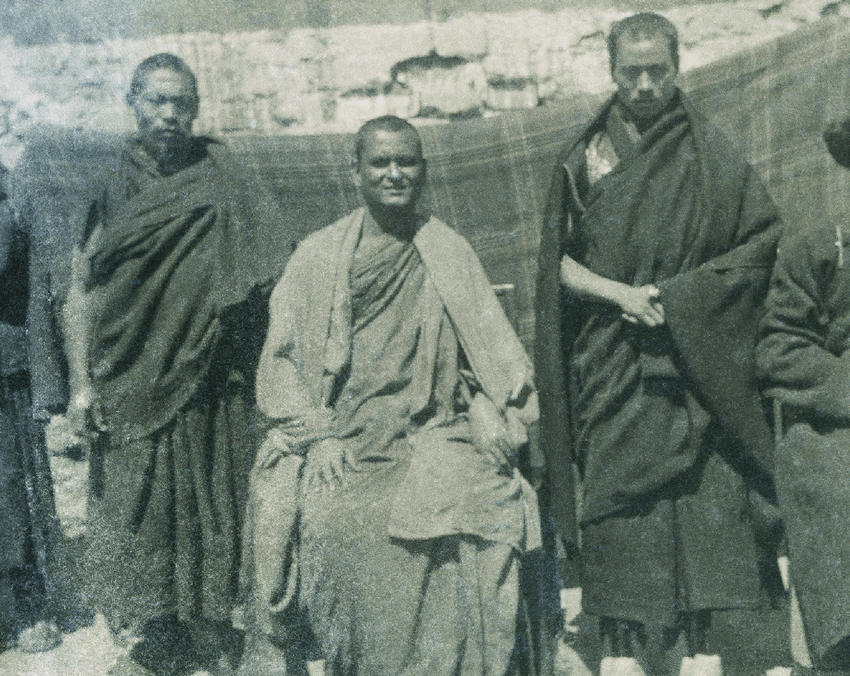

In addition to his political activities, Sankrityayan was a prolific reader and writer. Even while in prison, he read many books, including one on the Russian Revolution of 1917–23. He taught Vedanta and the Upanishads to his fellow prisoners, and gradually became a self-proclaimed communist. Around the same time, he became interested in Buddhist philosophy and traveled to Nepal to collect Buddhist manuscripts and literature. He was imprisoned again for political reasons on his return to India. He traveled to Tibet four times to study Buddhist literature and acquire a thorough knowledge of Buddhist philosophy, in the process collecting many valuable books and manuscripts from Tibet.

Due to his deep knowledge of Buddhist philosophy, Sankrityayan was engaged in teaching and research in Buddhist philosophy at the University of Colombo, Sri Lanka. The Mahabodhi Society of Calcutta helped him in this endeavour in many ways. He later learned Pali and Sinhala and concentrated on studying Buddhist scriptures. Attracted to Buddhism, he started practicing the spiritual tradition. In 1930, he changed his name from Kedarnath Pandey to Rahul Sankrityayan. The name “Rahul” comes from the son of the Buddha’s bodhisattva life and “Sankrityayan” was taken from his clan name “Sankritya.”

Sankrityayan remained active in political activities in addition to his learning. As a result, he was imprisoned many times but continued writing even in prison. He is said to have written the famous book Darshan Digdarshan during 29 months in Hazaribagh and Deuli jails.

Sankrityayan’s erudition did not go unnoticed. As a result, while he was in Russia, he received an offer from Leningrad University to teach. Responding to their call, he taught there for some time, returning to India from Russia in 1950. He later joined Vidyalankar University in Sri Lanka (then Sinhala) as a teacher.

Sankrityayan wrote many books on Buddhism and culture, and even as a self-proclaimed Marxist did not renounce his Buddhist faith. By studying Buddhist texts from Tibet, he did extensive research on Bengali Buddhism and came to see the Buddha’s philosophy as consistent with atheism. As a result, he came to study the original texts of many Buddhist scholars, such as Nagarjuna, Asanga, Vasubandhu, Ratnakirti, and others. Subsequently, he wrote many books on Buddhism and philosophy which are still popular in India’s literary world. Sankrityayan also wrote about 23 books in Pali and Sanskrit, among them Abhidharmakosha, the Khuddakapatha, and the Mahaparinirvana Sutra.

In Sri Lanka, Sankrityayan was given the title “Tripitakacharya.” He was also awarded the title “Sahitya Bachaspati” at the Allahabad Hindi Literary Conference in India for his contribution to Hindi literature. He received honorary doctorates from many universities, including Bhagalpur University. In 1963, the government of India conferred on him the Padma Bhushan award in recognition of his scholarship. Prof. Radha Banerjee Sarkar, head of the East Asia collection at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts, said:

“One of his major contributions was to turn the lens on the way faiths and cultures interconnected, to attempt for a holistic view of the continent. We have a habit of studying iconographies and histories in isolation, which is why we fail to see the way Buddhism and Hinduism interacted. Rahul was perhaps the first person to give a complete view of this interactive history, through his texts, the travels and the artefacts he brought back.” (Hindustan Times)

Toward the end of his life, Sankrityayan suffered from chronic illness. He was said to have suffered from diabetes for some time and later developed amnesia. He was treated at a hospital in Calcutta to restore his memory, and was later taken to Moscow for further treatment after his condition did not improve. Seven months in Moscow did not help, and was brought back to India on 23 March 1963. On 14 April 1963, he passed away at Eden Hospital, Darjeeling, at the age of 70.

Sankrityayan was initiated into a traditional religious culture and received education under many teachers and monks. However, he had a humanist and modernizing attitude that served him well as a pioneering writer and scholar. He studied almost all the religious literature of India and ultimately settled on Buddhism as his life’s vocation. Such was his devotion that his very name was a reminder of his personal faith: “Rahul Sankrityayan.” With more than 150 books attributed to his authorship, editorship, and translation, it will be supremely difficult to find another like him in the 21st century.

See more

The versatile genius of Rahul Sankrityayan (Hindustan Times)

Rahul Sankrityayan’s Work on Caste Is Necessary But Also Invokes Questions of Dalit Agency (The Wire)

My father told me about him many years ago. Trully an intellectual.