Won Buddhism grew out of the movement to reform and renovate Buddhism for the modern world during a transitional period in Korean history. The revitalization and progress in politics and economics also extended to the role of gender in Korean Buddhism’s encounters with modernity.

The founder of Won Buddhism, Sot’aesan, was born in 1891, around the time when indigenous Korean folk religions such as Tonghak and Chŭngsangyo had an influential presence, especially in southwestern parts of Korea. According to these indigenous traditions, this moment of transition marked the “close of the older heaven and the opening of the later heaven.” The older heaven is depicted in this cosmology as a time of absurdity, immaturity, exploitation of the weak, separation and division, inequality, and injustice, whereas the later heaven is a time of peace, self-reliance, rationality, equality, justice, and prosperity.

The movement toward gender equality was another example of the change from an “earlier heaven” to “opening a later heaven.” Under the Confucian social ethos of Chosŏn society, the roles of women were largely confined to the domestic sphere. Women received only an informal education at home and were required to observe the Confucian virtues of diligence, filial piety, and chastity. But by the early 20th century, new popular magazines had developed the concept of the “New Woman” (K: sinyŏsŏng), which helped Korean women create a new gender identity.

Yi Chŏng-Chun (1886–1955), a former courtesan who later ordained as a Wǒn Buddhist nun, would become one of Sot’aesan’s first female disciples. Yi’s story shows modernity’s impact on the psyche and social roles of Korean women, and also exemplifies the progressive initiative of male teachers to advance the status of women in society. These men understood that the growth of religious movements relied on promoting gender-equal relations.

Yi Chŏng-Chun, formerly known as Yi Hwa Chun, was born in 1886 in southwestern Korea to impoverished parents, conditions that led her to become a kisaeng (courtesan). There are no records documenting Yi Hwa Chun’s years as a kisaeng. Kisaengs rose to prominence during the Koryŏ dynasty and are first mentioned in the early 11th century, (Hwang, 449) but in the Chosŏn period, with the dominant Korean Confucian ideals, the view of this profession grew dim. By the time Hwa Chun entered this lifestyle, the elegant and intelligent kisaeng during the Chŏson dynasty were replaced by an image of third-grade sex workers, a stigma that affected kisaeng during the 35 years of the colonial period. (Lee, 73)

As traditional kisaengs became tainted and prostitution grew increasingly widespread, they began to participate in the public forum. Hwa Chun was still far from voicing her own opinions on gender equality. After some years as a kisaeng, she met her husband Kim Dae-gyu, a member of the provincial assembly in Jeolla Province and a wealthy landowner who operated a rice mill. She was his third wife and was skilled in administrative affairs, which she utilized to assist him in running the rice mill business. Just as Korean society was going through a transitional phase from the “early heaven” to the opening of the “later heaven,” Yi Hwa Chun would also experience a significant transition in her life from female courtesan and submissive wife to religious pioneer and leader.

Her first awakening happened at the rice mill, which had an area that raised pigs. After watching two pigs copulate, she had a profound awakening and felt as if someone had removed the skin from the pigs and covered her face. She thought to herself, how is my life any different from these pigs? At this point, she yearned for a new way of life. (The Doctrinal Books of Wŏn Buddhism, 402) Soon after, she left her marriage and moved in with her uncle, who at the time practiced Bocheon-gyo, a Korean shamanic tradition, but she was unsatisfied. On numerous occasions, he introduced her to teachers, but she felt constantly let down.

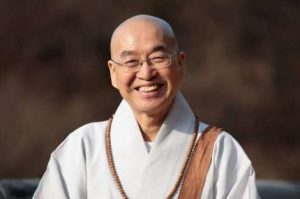

At age 38, jaded by the “pleasurable life,” she sought for spiritual guidance from her uncle. She met Sot’aesan in the summer of 1924 and decided to enter the order. Sot’aesan gave her the Dharma name “Chŏng-Chun” which means “always full of life like a spring day.” She became Sot’aesan’s 32nd female disciple. However, not all of the existing members welcomed her. The Discourses of the Founding Master provides a well-known account that depicts this specific circumstance:

When the Founding Master was staying in Yŏngsan, a few prostitutes joined the order and occasionally visited the temple. Those around him were bothered and said to the Master, “If such people visit our pure Dharma site, then not only will outsiders laugh at us but it will also become a hindrance for our development. We think it best if you do not let them visit our temple anymore.” The Founding Master smiled and said, “How can you say such petty things? Generally, the great intent of the Buddhadharma is always to deliver all sentient beings everywhere in the spirit of ‘great loving-kindness and great compassion.’ How can we let go of our original duty because we fear others’ ridicule? What is more, in the world there may be both high and low classes of people as well as high and low occupations, but in buddha-nature there are no such distinctions. If you do not understand this fundamental principle and dislike practicing together with them when they visit the temple, then you are the people who are difficult to deliver.”

(The Doctrinal Books of Wŏn Buddhism, 392)

Sot’aesan directed their attention to Il-Won-Sang, the object of faith and the model of practice in Wŏn Buddhism. The truth of Il-Won is expressed as a circle (O) and is described as follows: “Il-Won (One Circle) is the original source of all things in the universe, the mind-seal of all the buddhas and sages, and the original nature of all sentient beings.” (The Doctrinal Books of Wŏn Buddhism, 20) In Sot’aesan’s view, all beings, despite the diversity and plurality of the phenomenal world, are of one noumenal reality. The source of all things in the universe means the truth of Il-Won-Sang is the root of all existence in the universe. As such, all things in the universe are fundamentally equal. When we awaken to existence at this level, there is no male or female, nor old or young.

Wŏn Buddhism teaches that learning about how the mind functions is one method to overcome the gender bias that people habitually hold. According to Sot’aesan, social change requires reorganizing the system, but what is most urgent is a “mind revolution” not a social revolution. The effect of practice is that one becomes less ideological, less tied to rigidly held fixed beliefs.

Sot’aesan made important improvements to the Wŏn Buddhist community based on the Il-Won-Sang principle, including equalizing spiritual training for men and women. The majority of colonial Korean women had only basic schooling and educating women continued to be viewed as a threat to traditional Confucian values. Sot’aesan believed that women, just like men, should receive an education that would allow them to function actively in human society. He went further to say that after marriage, each spouse should maintain financial independence. According to Sot’aesan’s axiology, the causes of all contradictory social structure are based on people’s ignorance. The unbalanced opportunity of education was the cause of unreasonable discrimination and the contradictory social structure of old society. (Hahn, 262)

At the very beginning of Wŏn Buddhist history, Sot’aesan gathered all of his disciples, whether or not they were ordained, for a fixed-term training program. Most of his earliest female disciples were married, yet he treated them without distinction. He encouraged his female disciples to go beyond their social and historical boundaries, and to try to heighten their awareness and build new lives according to their enlightenment of the truth. (Hanh, 255) Therefore, from the beginning of Wŏn Buddhist training, Sot’aesan educated and empowered women to have self-confidence to be ministers equal in power to men. The lectures he delivered to his female disciples during the formative years of Wŏn Buddhism would reveal his convictions regarding the modern status of women.

References

Committee for the Authorized Translations of Won-Buddhist Scriptures, trans. 2016. The Doctrinal Books of Wŏn Buddhism. Iksan: Wŏn’gwang Publishing Co.

Hahn, Myung-Hee. 1997. “A Comment on ‘The Function of Social Education for Women in Won Buddhism’: Women’s Equality to Men adopted by Sotaesan.” Korean Journal of Religious Education 4: 251–65.

Hwang, Won-Gap. 1997. Han’guk sareul bakkun yeonindeul. Seoul: Ch’aek e ineun maeul.

Lee, Insuk. 2010. “Convention and Innovation: The Lives and Cultural Legacy of the Kisaeng in Colonial Korea (1910-1945).” Seoul Journal of Korean Studies 23: 71-93.

Related features from BDG

A Short Introduction to Won Buddhism

My Journey on the Path of Won Buddhism

From Seoul to Somerville: The Founding of a Korean Won Buddhist Temple in Massachusetts

Women in Buddhism: Breaking Gender Stereotypes

We Become Who We See

Related news from BDG

New Korean Buddhist Temple to Open in Bodh Gaya, India

Permanent Endowed Chair in Korean Buddhist Studies to Be Established at UCLA—A First Outside of Korea

Buddhist Nun Teaches Sustainability at Stanford with Korean Temple Cuisine

Association of Korean Buddhist Orders Publishes Buddhist National Treasures of Korea

Buddhist Nun Publishes English Cookbook on Korean Temple Food

Special issues from BDG

BDG Special Issue 2018: Women of Buddhism: