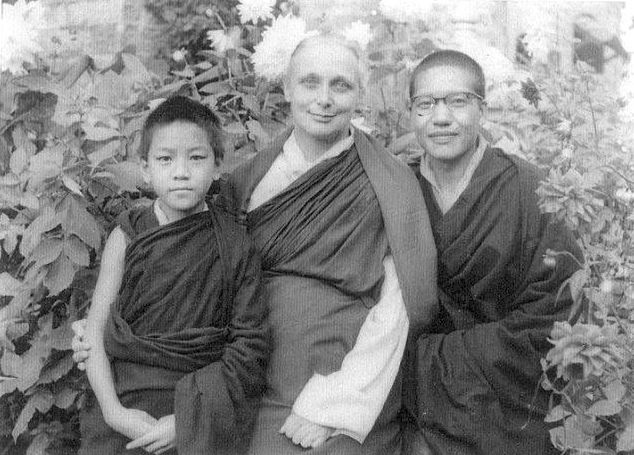

Fifty years ago, an English woman, Freda Bedi, became one of the first Westerners to be ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist nun some time after her work providing refuge and education for young lamas who had made the perilous journey across the Himalayas from Tibet to India had helped to bring their plight to the world’s attention. A few years after her novice ordination, Sister Palmo, as she became known, was the first woman in the Tibetan tradition to take full bhikshuni ordination. She later accompanied the 16th Karmapa (1924–81), her spiritual teacher, on his first visits to the West.

Throughout her life, Freda (1911–77) crossed boundaries—of religion, race, and nationality. Born Freda Houlston in a back street in England’s Midlands, above her father’s jewelry and watch repair shop, she led a life on the move: from Oxford to Berlin, Lahore, Kashmir, Delhi, Dalhousie, and Sikkim. She was already in her forties and married with three children, when she first encountered the Buddhist teachings and practices of meditation. “It changed my whole life,” she declared.

Freda’s spiritual quest had begun decades earlier in her home city of Derby. She remembered her father, Frank Houlston, as a deeply religious man. But those memories were slender. She was only 7 years old when her father was killed on the battlefields of northern France in the closing months of the First World War. Her mother was so distraught that she rejected all religious observances, but respecting what she believed would have been her late husband’s wishes, she encouraged Freda and her younger brother to attend church and Sunday school.

As a girl, Freda found the pervasive sense of loss difficult to deal with, recalling how she often came close to fainting during the annual Poppy Day remembrance services for the war dead. She was confirmed in the Church of England, but didn’t like the local vicar and his emphasis on the petty and parochial. Her parish church did provide solace in one regard, however: without telling her family, Freda often began the day with an hour of contemplation alone in the church. These visits, she recognized in later life, were her first faltering steps in meditation.

Freda also read voraciously—the writings of the Anglo-Catholic Oxford Movement and of converts such as Cardinal Newman, as well as the lives of medieval saints. As a student at a women’s college at Oxford in the early 1930s, she was regarded by her friends as religiously minded, but she rejected conventional Christian observance. Left-wing politics attracted her, and so too did the tumultuous debates at the Majlis, the Indian students’ society.

A few days after her final degree exams, Freda married her Sikh boyfriend, Baba Pyare Lal Bedi (better known as B.P.L. Bedi [1909–93]). He was a Punjabi from an elite background—part of a feudal family, as he put it—but he had been won over at Oxford to Indian nationalism and communism. Although his family traced their ancestry directly to Guru Nanak (1469–1539), the founder of the Sikh religion, he was not observant.

From England the couple moved to Germany, where they had their first child, a son they named Ranga. After a few difficult months in Berlin just as Hitler was tightening his grip on power, the Bedis decided it was time to set sail for India. “Although I should have felt a stranger being in a strange country, I felt very much at home,” Freda told an old Oxford friend. “I loved India from the moment I put my foot on Indian soil.” She came to believe that this was something to do with thought formations coming from former lives.

In British-ruled Lahore (now in Pakistan), the Bedis lived in striking simplicity in a cluster of thatched huts on the outskirts of the city. Freda wrote for newspapers and taught English at a women’s college. She always wore Indian clothes and relished Indian food. Both she and her husband were prominent in the independence movement, and campaigned for civil liberty and on behalf of Punjab’s impoverished peasantry. During the Second World War, both were jailed for opposing India’s involuntary support for the war effort—Bedi as a communist and Freda as a follower of Mahatma Gandhi.

Srinagar, 1948. From wikipedia.org

After India’s independence and partition in 1947, the family—their second child, Kabir (now a global film star), had been born the previous year—moved to Kashmir to work for the progressive state government. It was here that Freda’s interest in India’s religions developed. The family still has her copy of the Koran from this time, and she chose to live for a few months in turn as a Muslim and a Hindu, without finding the spiritual path she sought.

In 1952, Freda accepted an assignment with the United Nations in Burma (now Myanmar) that lasted several months. She left her husband and three children (her daughter, Gulhima, was born in 1949) behind in India, and found that in Rangoon she had an opportunity to learn meditation, guided by a “most remarkable” Buddhist teacher, Sayadaw U Titthila. “After about eight weeks, I got my first flash of understanding. I got great, great happiness—a feeling that I had found the path,” she recalled.

On her return to India, Freda Bedi told her family that she had become a Buddhist. Her children supported their mother’s decision, and her husband by then was embarking on his own spiritual journey—initially studying the occult and later embracing Sufism and spiritual healing. Kabir went with Freda on one of her subsequent visits to Rangoon, and briefly became a novitiate monk, wearing the robes and with shaven head.

When, in 1959, the Dalai Lama and thousands of other Tibetans fled across the Himalayas to escape Chinese repression, Freda—by then the editor of an Indian social work journal—volunteered to help out at the hastily established reception camps in northeast India. “I felt with my particular background, both as a Buddhist and as a mother and social worker, perhaps I could help in the refugee camps.”

The Indian government took her up on the offer, and for six months she worked at Misamari and Baxa in Assam. She became well acquainted with the problems faced in particular by young lamas and their spiritual teachers. “About a quarter of the total refugees must have been lamas,” she remembered. “And nobody quite knew what to do with them.” Freda became absorbed by Tibetan spirituality. “Tibetans are highly evolved spiritually, and a rather extraordinary people,” she confided to a friend. “I also feel, having worked among them for some time, that there’s something very special about these children.”

Freda arranged for two lamas, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche (1939–87) and Chöje Akong Tulku Rinpoche (1939–2013), to come and live with her family. With the support of the Dalai Lama and the Indian government, she set up a small school in Delhi to help the young Tibetans adjust to their new home, offering lessons in English and mathematics as well as spiritual instruction. The Young Lamas’ Home School quickly relocated to the more temperate climate of Dalhousie in the foothills of the Himalayas, not far from Dharamsala. Among the scores of young men who studied there are such notable teachers as Chime Rinpoche and Lama Yeshe Losal Rinpoche.

All the young lamas called her “Mummy”—a title she liked, and indeed insisted upon. Her concern for the welfare of Tibetan nuns among the refugees prompted her to set up a nunnery, established in Dalhousie before moving to its present location in Tilokpur, near Dharamsala, it has 65 nuns and is the oldest Kagyu nunnery outside of Tibet.

The deepening of Freda’s spiritual knowledge and the guidance of the 16th Karmapa eventually prompted Freda to seek ordination. She took the robes in 1966—with the support of her husband but without informing her children in advance.

“I suddenly saw her and she had shaved her hair and she was in robes,” recalls Kabir. “And firstly there was the shock of seeing her like that. And secondly this terrible feeling of betrayal, that she hadn’t told me before she did it.” Kabir was given the task of telling his sister, then just 16, whose reaction was even more wounded and angry.

In a matter of months, Freda’s children were reconciled to their mother’s new vocation and came to take great pride in her remarkable life. As a nun, Freda was still able to see and visit her family, and when she travelled abroad with the Karmapa, she would return loaded with gifts including, incongruously, smart children’s clothes and comfortable underwear, then not easily available in India.

Two years after ordination, Sister Palmo entered a year-long retreat at Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim. An old friend visited her there and asked if she had any regrets about all that she had given up. “You see, I have no regrets at all,” the nun replied. “Because what had to be given up is given up. It fell off naturally—like an apple falling off a tree. And we don’t have to give up loving those who are near and dear to us. We have to give up attachment, which is a different thing.”

Andrew Whitehead is writing a biography of Freda Bedi. He would be delighted to hear from anyone with memories of her and can be contacted at [email protected]