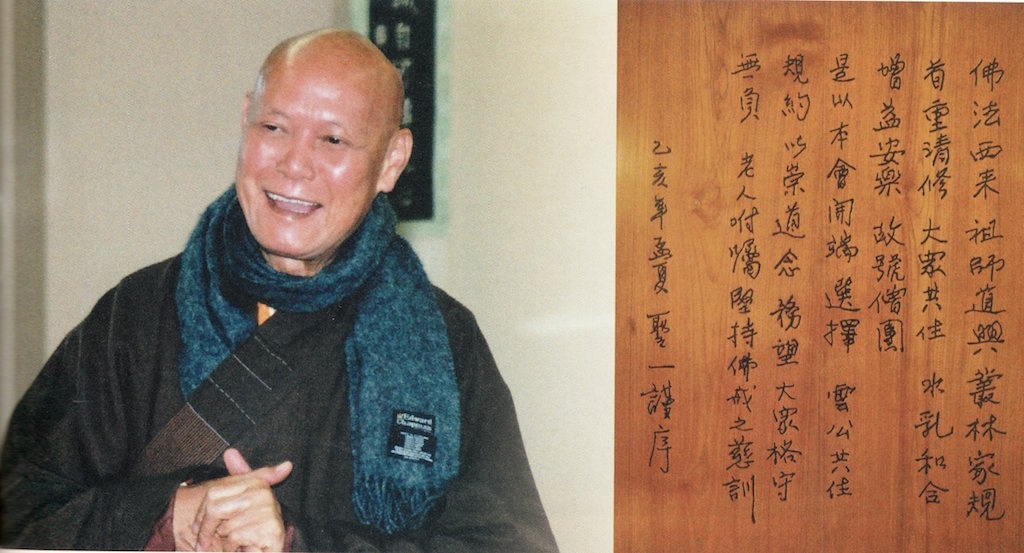

In the late spring of 1994, my teacher Venerable Sing Yat (Sheng Yi) gave a teaching tour in Canada during which he traveled to Toronto and Vancouver. The trip was an especially inspiring one because after returning to Hong Kong he asked Venerable Yin Yeung and myself, who were both still junior nuns at the time, to go to Canada to set up a nunnery. So we moved to Canada and located a suitable property, and in 1995 Venerable Sing Yat endowed the newly established nunnery in Chilliwack, BC, with a teaching of far-reaching mission and vision, written in his own calligraphy:

With the coming of the Buddha’s teachings to the West,

May The Path to practice the teachings of the past and wise teachers flourish.

Adhering to a simple spiritual life,

This is the most cardinal etiquette of a monastic community.

Living harmoniously and peacefully together,

Like milk in water,

Complimenting and benefiting each other in the practice,

As such is called the sangha.

Since its conception,

Po Lam has chosen the house rules

As taught by Venerable Master Hsu Yun,

To commemorate and honor his teachings.

This statute is expected to be observed with vigilance and diligence

In order not to fail the elder for his compassionate teachings of

Upholding ethics and morality as taught by the Buddha.

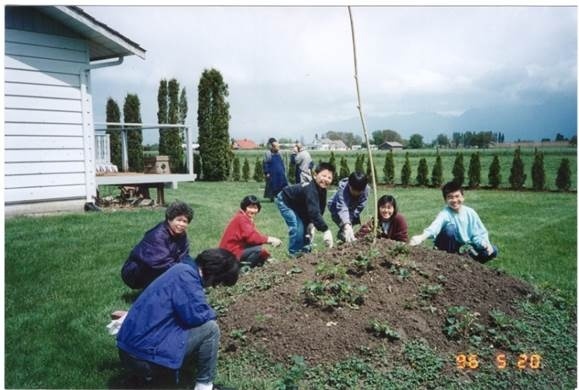

We moved to what is now Po Lam in Chilliwack on 12 February 1995. It was very challenging coming to a new place; the weather was cold, we had no local friends, and the culture very different. Eventually, some Chinese volunteers began to come to Po Lam in 1997 and a congregation from the outlying Chinese community began to form, but those early years in our new home were often lonely and difficult. I remember Chinese New Year in 1996 was very cold, with a severe snowstorm. There was just Venerable Yin Yeung and myself, and we held a Medicine Buddha Penitence Ceremony—just the two of us. We did have some very keen Taiwanese supporters in those very early days and we are forever grateful to everyone who supported us through those difficult years.

Living out in Fraser Valley was difficult for various reasons. We knew hardly anyone at all and Chilliwack did not have many Chinese congregation members. In the early days, many people we met from Vancouver told us that Chilliwack was a very religious place, where Christianity was flourishing. The people we met in the area were surprised and curious to know why we had chosen this location and what we were doing there. I told them that we were using this quiet place to grow spiritually and to mature on our path of practice. We could sense their fear; it was as if we posed a threat to their society. Eventually we began to realize that just keeping to ourselves and practicing in Po Lam, with minimal interaction with the lay community, was not going to get us anywhere. We slowly began to establish relationships with the locals.

In those early days, our chanting and evening services were carried out in Chinese, which was not very conducive for English-speaking people interested in learning the Dharma. I began to understand that our mission was to understand the needs of people in the West and to adapt ourselves in a way that would allow us to spread the Buddha’s teachings in a relatable and transparent way.

Keeping this goal in mind, there were many things to consider: Firstly, language and the related challenges of understanding the complexities of the Mahayana teachings. Secondly, exposure to Buddhist culture and the Buddha’s teachings in the West is at a very early stage; the Buddha’s teachings have been known in Canada for slightly over 200 years. Compared with a history of more than 2,000 years in Southeast Asia, we needed to be aware that it was not realistic to expect Westerners to be as receptive to Buddhist culture and the teachings as we are—especially the Mahayana teachings.

With this in mind, we decided meditation would be a great practice to offer. During the first few years of teaching one-day meditation courses, I was still hesitant to push things onto people that might appear to be too “Buddhist.” I decided at the very beginning to cover the shrine housing the large statue of the bodhisattva Di Zhan Pu Sa with a curtain so that those students who came for meditation classes would find the place more religiously neutral. I wanted them to learn the meditation technique with an open and receptive mind, and not be preoccupied or dissuaded by the religious symbols that are used in a Buddhist nunnery. Nowadays, the shrine is an accepted and integral part of who we are at Po Lam.

With the meditation practice firmly established, I began teaching the Dharma, giving weekly classes even though in the beginning the classes were very small. Gradually the class grew as more people started to come and learn. I soon discovered that teaching Western students was quite a different experience and posed new challenges. For one thing, teachers and students behave quite differently in the West than they do in the East, where teachers are accorded deep respect and are expected to correct their students swiftly and directly. In the West, teachers are expected to encourage far more than correct and are also not respected in the same way. The balance is completely different.

Initially, I stuck to the traditional Chinese way of teaching, but there seemed to be such a big gulf between the lay people and the sangha. People were hesitant to approach, to ask questions, or to share their feelings. I began to realize that I did not like it that way myself; I felt that our communications were too guarded and tense. I called our first English Dharma classes, “Dharma Sharing,” because I wanted to encourage interaction and a real sense of sharing and relationship.

Over time, I learned to adapt my way of teaching to a more relaxed and often less formal style that is very different from the way I was taught when I was a student. I have found that students in the West who are treated in this way respect the way I teach them, my knowledge, the way I try to help, and of course the way I share with them and show that we are all human—including myself and the other monastics. This is good, but it also poses its share of difficulties. I often need to explain to Western students why some things cannot be done in certain ways, such as how and why we make offerings to the Triple Gem. This must come from a thorough understanding and experience of one’s own volition and position in a monastic setting and, most of all, from having sufficient humility to cultivate respect for the Triple Gem.

Choosing what to teach Westerners in my Dharma classes and when to teach was a great learning experience. Initially, I concentrated on ancient Indian Buddhism, where the focus is on the original words of the Buddha. This helped to build a strong foundation of the fundamentals of the Buddha’s teachings. Although the main emphasis of our practice is on mindfulness, introspection, understanding the truth of our existence, and the cultivation of loving-kindness, the importance of serving others in the community to cultivate our own perfections, such as generosity, tolerance, and diligence, is another crucial tier of advancement. In the past few years, the students have become increasingly ready and receptive to learn more about Mahayana practice and the Bodhisattva Path. I am glad that they have slowly and gradually started to realize and experience that these practices actually run parallel and complement each other.

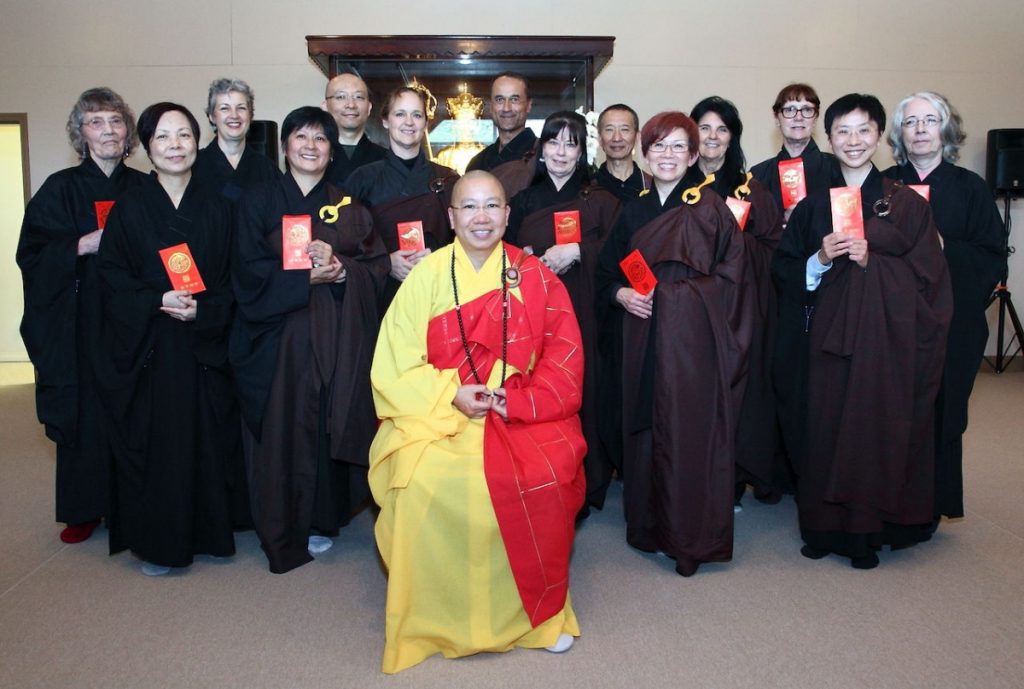

The challenges of blending two cultures have brought many rewards and much inspiration. We monastics are bilingual and our congregation comprises members of both the Chinese and Western communities. This combination is very rare in many Buddhist religious settings. It has been wonderful and very gratifying to see mutual respect, understanding, learning, and harmonious teamwork between the two cultures begin to blossom and grow over the years.

Po Lam is also unique because of its engagement in mainstream community work, with three main branches of community-engaged services. The first is the Compassionate Centre for Health, which sends volunteers to visit senior care homes and palliative care units. The second is our program that leads meditation sessions in federal prisons, and third, our local community engagement. In this last branch, we offer educational courses and mindfulness meditation in the community and surrounding areas at hospices, public schools, and community service organizations.

In addition to the challenges already mentioned, one of the very biggest obstacles that we encounter is financial. Many are very surprised and some even think it is a miracle that Po Lam has managed to exist for 21 years in such a remote place. It is at least an hour away from the main Buddhist population in BC. We do not provide any name plaques for dedication like other traditional Chinese temples, and we do not perform any ritualistic ceremonies. Yet it seems that there are always people who remember us. Occasionally, they send us a check for C$20, C$30, or C$100, and those heartfelt tokens support and encourage us to continue our hard work, maintain our very simple lifestyle, and keep Po Lam going.

When Ven. Sing Yat came here to rest for three months in 2000, he asked us to redevelop the premises and build a bigger meditation hall, and since then we have been working without wavering toward that goal. When the property next door became available in 2006, we tried to purchase it. Po Lam did not have the financial means to acquire the land, so I approached some of the members of our congregation, who freely gave loans without any expectation of interest and no timeline for repayment. We are truly, forever grateful to these people for their wonderful generosity.

In order to continue spreading the Dharma in the West and seeing our teacher’s vision come to fruition, we are dependent on the dana* of a relatively small number of practitioners. The crux of this challenge lies in sharing the Dharma and increasing our congregation while illuminating and increasing the Western understanding of dana, which is very different from the Eastern point of view. Without support, the Dharma cannot continue its journey and establish roots in the West. It is difficult to explain dana in the correct light without an understanding and appreciation of the Dharma. Here in the West, this is a very delicate balance and terrifically challenging at times.

People have said it is a miracle that we have survived for the last 21 years and that it was a miracle we were able to acquire that additional piece of land in 2006. They also say it is a miracle that we were able to rezone our land. Now we are finally starting to build and people are saying this is the fourth miracle. I do not think these are miracles; I think Po Lam is meant to be here. Po Lam is beginning to receive more support locally and we are spreading the Buddha’s teachings to growing numbers of local people because we do not emphasize religious conversion, rather we focus on mental conversion and spiritual transformation. That simple distinction eases many Western people’s minds, making them more willing to listen and open their hearts to receive the teachings of the Buddha. This is a very happy outcome and an immense reward to those of us who have strived so hard to maintain Po Lam to this point.

Once the Po Lam Meditation Vihara is complete it will become a landmark from which Dharma will flourish in the West.

* Sanskrit; the virtue of generosity and charity.

Back to Tradition and Innovation: Chinese Buddhism Beyond Asia Special Issue 2016