In my introductory article for this column, I discussed my initial encounter with Buddhist teachings, my growing interest in them, and the development of ideas behind my PhD thesis project titled “Mindfulness, Interbeing and the Engaged Buddhism of Thích Nhất Hạnh.” In this article, I will share how I began my mindfulness practices and encountered the teachings and practices of Thích Nhất Hạnh.

During my master’s degree in Buddhist Studies at the University of Hong Kong in 2004, I took a course titled “Mindfulness, Stress Reduction and Psychotherapy.” This course was based on the eight-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn in the late 1970s. The practices taught included sitting meditation, body-scan meditation, mindful yoga, and various techniques aimed at enhancing awareness of mind and body. Everyone in the class was required to spend a minimum of 45 minutes a day, six days a week, engaging in these mindfulness practices for at least eight weeks. This course served as my introduction to mindfulness practices.

The MBSR program was highly intensive, yet incredibly beneficial for me. In fact, had I not taken this course, which focused on the practice itself, my master’s degree in Buddhist Studies would not have been as fulfilling. As I discussed in my previous article, transformation demands more than mere textual study and analysis; it requires actual engagement with the practices.

In addition to learning mindfulness practices, the course also required readings and assignments. Anger: Wisdom for Cooling the Flames, one of the items on the course’s reference booklist, was the first book by Thích Nhất Hạnh that I read. This is also how I was introduced to this great Zen master. I found the contents of this book straightforward and accessible. It helped me better understand the nature of anger and how mindfulness could transform this strong emotion. However, I did not fully appreciate the simplicity and applicability of his teachings at the time. While I found the book thought-provoking, it did not leave me with a strong desire to seek out his other writings.

The course also introduced a song that is commonly used in Thích Nhất Hạnh’s monasteries and practice centers around the world. Titled “Breathing In, Breathing Out,” the song is essential to the Zen master’s practices. It consists of simple melodies and is sung with simple hand gestures that correspond to the lyrics. The lyrics of the first half of the song are: “Breathing in, breathing out, I am blooming as a flower, I am fresh as the dew, I am solid as a mountain, I am firm as the Earth, I am free.” The song seemed like a children’s song to me. I thought it should be taught in kindergarten, not to adults. Although I was following the singing and hand gestures, I was reluctant to engage with it in my mind.

Thích Nhất Hạnh is well-known for his use of simple and repetitive guiding phrases in sitting meditation. The in-breath and out-breath are paired with guiding phrases to help maintain mindfulness. These phrases are often used at the beginning of the practice: “Breathing in, I know I am breathing in. Breathing out, I know I am breathing out,” which are then shortened to just the keywords “in, out.”

However, when this practice was taught in the class, I did not find it helpful at all. After hearing the guiding phrases mentioned above, I thought: “What? Breathing in, I know I am breathing in? Breathing out, I know I am breathing out. . . ?” My mind went on to criticize how silly it was to say these words. As a result, I could not concentrate on my breathing. I tried the practice a few times after class, but each time my mind became distracted and overly critical instead of staying focused on the breathing and phrases.

These were my very first encounters with Thích Nhất Hạnh’s teachings and practices. As described, I was not very interested in them. Therefore, I mainly practiced mindfulness following the instructions of MBSR and read books about the related practices by other writers.

Then, one day in April 2007, I saw a poster about Thích Nhất Hạnh’s upcoming visit to Hong Kong. His visit in May of that year included a five-day mindfulness retreat, a Day of Mindfulness, and two public talks. I somehow felt that I should get to know more about this renowned Zen master. Seeing him in person, a rare and valuable opportunity, seemed like the perfect way to do so. I thus decided to attend one of his public talks at the Wu Kwai Sha Youth Village.

At the village hall where the talk was conducted, a group of Thích Nhất Hạnh’s monastics first entered the venue and sat on the stage. One of the monastics led a short sitting meditation using the guiding phrases (and variations of them) mentioned earlier. As the meditation began, I was surprised to find my usually critical mind seemed quieter, despite some inner chatter persisting. I wondered why the experience felt so different from my past reluctance to embrace those guiding phrases.

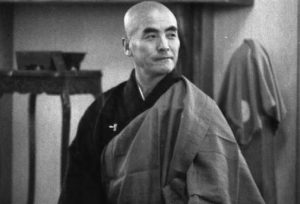

Thích Nhất Hạnh then slowly walked into the hall. There were a lot of audience members and my seat was quite far from the stage, yet I could sense his solemn and calm demeanor. Before he began his talk, Thích Nhất Hạnh told the audience that his monastics would offer a chant, reciting the name of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. I initially expected traditional Buddhist chanting, however it was nothing like that at all!

The chant, more like a song, featured a simple and beautiful melody, repeatedly reciting the name of “Avalokiteshvara.” Accompanying the chant, two of the monastics played a guitar and an African drum, while Thích Nhất Hạnh punctuated the melody with the sound of a standing bell. I was surprised to see the use of guitar and African drum in the chant! I had never imagined that those instruments would appear in a Buddhist setting.

The chant, which blended various traditional and modern elements, transcended cultural, musical, and traditional boundaries. I found the sound very healing and soothing. Although it lasted more than 10 minutes, there was not a single moment when my mind wandered off. I was deeply impressed by the creative and impactful way the chant was presented.

After this initial first-person encounter with Thích Nhất Hạnh, I became very interested in his teachings and practices. But the story did not end there. A month after the talk, I attended a multimedia theatrical performance of the Hua-yen Sūtra at the Hong Kong Cultural Centre, based on the original translation by Thích Nhất Hạnh. Even before the performance began, I experienced its transformative power. How could that happen? I look forward to sharing more with you next time!

Related features from BDG

Formative Encounters with Thích Nhất Hạnh’s Teachings and Practices, Part 2

Formative Encounters with Thích Nhất Hạnh’s Teachings and Practices, Part 3