The Buddha gave us many methods to facilitate the investigation of our own minds. With conscious intention and some determination, we can end or greatly alleviate our mental and emotional discomfort—by recognizing and tending to our often unconscious and unskillful patterns of conditioned behavior. By bringing our patterns of mind to our conscious awareness, we have the choice to keep them or to let them go. We have a real opportunity not only to relieve our own suffering, but should we choose to, also to help others to do the same.

The incredible variety of investigatory practices that were offered during the lifetime of the Buddha and persist until this day, including inquiry, self-reflection, meditation, mindfulness, and loving kindness and compassion, also came with very kind instructions to work with our heart-mind while we are seated, standing, walking, or even lying down. I have always taken this guidance to heart and utilized my body as the doorway—the mirror—to my mind, and viewed it as my current, albeit temporary, home.

Whether the focus of our attention is on sensations in the body as they come and go, change, and rearrange themselves, or on the breath as it comes and goes, moves our skin, ripples outwards towards our muscles, and shifts our clothes, we can utilize mindfulness of the body as our anchor to the present moment. Literally feeling, rather than conceptually getting caught in thinking about, the breath—being immersed in the felt sense of it—can be a rich and dimensional exploration of a culmination of sensations at any given time.

Of course, this is much more difficult than it sounds, and any of us who have meditated for even just a short while know how slippery the present moment is, how easily we leave our bodies and are onto the next thought, feeling, meeting, or text. Even while seated on a chair or a cushion there is tremendous internal movement in the mind and heart; stillness can be elusive and something we have read about but haven’t quite experienced for ourselves.

For many of us, being aware of the body or having the capacity to settle awareness on the breath is facilitated by some movement, such as yoga, Taiji, or even a brisk walk. After a movement practice we are more likely to be able to literally feel the body, settle the mind, and notice our breath and sensations. My personal doorway into sitting meditation was a yoga practice. My yoga practice preceded my meditation practice—it prepared me to sit still and pay better attention to my thoughts and feelings—it wasn’t part of my meditation practice at first, but rather the support for it.

In fact, when I originally offered to teach some yoga postures on my Buddhist teacher Ajahn Amaro’s retreats, it was purely with the intention to help everyone sit with greater ease. I thought I could alleviate some physical suffering, and indeed this worked. Stemming from my personal experience, my intention at this stage wasn’t to see the postures as forms or shapes to meditate in—it was to help people find ease in their lower back, neck, and knees. Looking back, I see why some appreciated the classes and why others thought they were simply distractions in a silent retreat.

It wasn’t until some years’ experience teaching yoga on retreats and doing my own yoga practice on retreats that I was able to weave the Dharma teaching directly into the yoga. The view, the instructions, the guidance then became the content for the forms or shapes of the postures that I would both practice and teach. This happened organically and made perfect sense to me—our view, philosophy, and intentions guide everything we do, so why not a yoga practice? Why see a yoga practice, or being in a yoga posture, as any different than mindfully sitting, standing, walking, or lying down? And what if the goal of reducing or eliminating suffering in general was the motivation for a yoga practice rather than creating ease, comfort, and/or strength and flexibility in the physical sense?

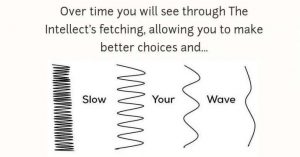

To facilitate not just mindfulness of the body but actual insights and wisdom, it is helpful to slow a yoga practice way down. Holding postures for longer and longer periods offers the time and space needed for our minds to register each moment. Holding postures for longer is similar to sitting in meditation—we are aware of how the body is feeling, how we are responding emotionally to what the body is experiencing, how the mind holds the experiences, and how the breath is responding or reacting to that precise moment. As we delve psychosomaticalIy deeper to know the breath and its habits intimately, it is beneficial not to manipulate or control it when we step onto our mat—by starting with a breathing technique, one can easily bypass how things are in that moment. Assessing the body, the heart-mind, and then the breath before we begin our yoga practice, we acknowledge where we are and how we feel so that we can know what practice, poses, or breath (such as Ujjayi) might be the most suitable for those conditions. Not asking or taking the time to know means that we immediately overlay the way things are with how we want them to be.

As we open different areas of our bodies, we have the opportunity to pay attention to how the breath responds and how our thinking or feelings might change or be influenced. Our bodies hold all of our previously unprocessed memories, thoughts, and feelings, so by releasing a particular part of the body we have the chance to bring what is being held into conscious awareness and then let go of what is no longer useful to hold onto.

We can also utilize the Four Noble Truths as a medical model to support the integration of Dharma and yoga: there is suffering or an illness and discomfort; there are reasons for the illness or pain; there is a cure; and here’s how to find relief as we practice mindful yoga. The goal, so to speak, of a yoga practice can therefore change to one of seeing things as they are and move away from trying to fix or change everything we don’t like or want to get rid of. If we are awake to how and in what ways we cause our own suffering, we can be on our way to releasing those unskillful patterns. Noticing our inner dialogue is integral to this process—our inner chatter as we “achieve” one pose or struggle in another is incredibly revealing. We can shift our emphasis away from the physicality of the posture so that the effort of doing a pose isn’t overlaying the inner process or internal conversations, but rather revealing them so that we are aware of what no longer serves us.

Intention and attention can become the main variants when embodying a shape or form of a posture rather than the shape or form itself being the most important aspect of what we are doing. Our intention to practice, if we care about being free from suffering, discomfort, or distress, needs to include a conscious intention to practice for our own, and others’, liberation. Whatever we are doing, and whatever shape or form or pose is required to do it, if our intention is to be at ease with what is and help others to do the same, it will fuel and provide the much-needed conscious content to the form of the body. We can practice with the intention to increase our kindness and compassion towards ourselves and others; we can practice to find greater understanding of our own heart-mind and body. We can include in our intentions to practice that of seeing clearly without the guise and disguise of the self, our story, or our conditioning.

Integrating Dharma into a yoga pose or practice can be as seamless as integrating Dharma into our lives. No matter whether we are practicing on a cushion, on a mat, or out in the world, attention to the way things are, intention to relieve or reduce suffering, and increasing kindness and compassion can be our guides and refuges. Whatever the shape or form of the body, whether standing, lying down, sitting still, or walking, we gain the capacity to be in the world, in the present, and to navigate our lives with more ease, wisdom, and kindness.

Jill Satterfield is a wellness program developer and international mindfulness and meditation teacher whose integration of mindfulness and embodiment practices include yoga, yoga therapy, and contemplative psychology. She has been in the field of integrative healthcare for over 30 years. Jill is also the founder of Vajra Yoga + Meditation, a synthesis of meditation and mindfulness of the body practices from the Buddhist tradition. Vajra Yoga + Meditation programs are included in and designed specifically for hospitals, addiction centers, Buddhist monasteries, yoga centers, and corporate headquarters. She is a faculty member of Spirit Rock Meditation Center’s Mindful Yoga and Meditation Teacher Training, UCLA’s Mindful Awareness Research Center trainings, and the Somatic Yoga Training in Marin, California, and the founder and director of the School for Compassionate Action: Meditation, Yoga, and Educational Support for Communities in Need. For more information, see her website.