After seeing several Cham festivals in remote places on a 2014 trip to Ladakh and neighboring Zanskar, I came to the conclusion that video-documenting Cham at dance festivals there is not the optimum way to help the dances to continue and improve. There is already too much accommodation of tourists and photography for the recordings to be of much value as records of the dance, and other ways would seem more effective than a scientific record of compromised performances. In Bhutan, by contrast, during the final five years of the absolute monarchy from 2003 until 2008, video-documenting festivals produced pristine records for posterity.

What is unique about Ladakh and Zanskar in regard to Buddhist Cham, a type of dance which dates to the 8th century with even earlier influences, is that every extant lineage of Vajrayana Buddhism has a monastery in the Ladakh-Zanskar region where Cham is performed. These lineages are the Nyingma, which is the oldest; the Sakya, once known for its brilliant high lamas; the Drikung Kagyu, with a reputation for excellence in meditation; the Drukpa Kagyu, with royal associations still in Bhutan and a legendary history at Hemis; the Karma Kagyu, which traces its founding to Milarepa’s teacher Marpa; and the Gelugpa lineage, known for the Dalai Lama.

Vajrayana is a form of Buddhism that was established using Cham dances: legend has it that Guru Rinpoche used Cham to subjugate the demons at Samye in Tibet, allowing for the building of the first Vajrayana monastery. Over the centuries, each lineage developed its own unique Cham tradition, its dances built up by capable choreographers and visionary yogis, both.

Sakti Gonpa, 2014. Photo by Jonathan Kendrew. From Core of Culture

Ladakh-Zanskar maintains a cultural ecology of Cham within the contemporary practice of high-altitude Vajrayana Buddhism, such that exists nowhere else—not in Tibet, where the traditions are repressed, nor in Bhutan, where only two lineages flourish. Ladakh is a mountainous border territory adjacent to China and Pakistan with a Buddhist-Muslim population, in a capitalist democracy, India; also in India, Zanskar is a stony beyul between the Zanskar and Great Himalaya mountain ranges, again Muslim and Buddhist, and inaccessible for nearly half the year. Dance gets through.

Tsomoriri, 2014. From Core of Culture

There is great dance interest in the Cham of Ladakh and Zanskar. Choreographically, it is a microcosm of many styles of Cham in one, essentially safe and free, region. Cham festivals, many moved from winter to summer to accommodate foreign guests, are becoming increasingly popular, with more foreigners attending every year. Depending on whom you talk to, the festivals have never been healthier, better attended, or more magnificent. The tourists, including the growing number of extreme sports enthusiasts, have more than a passing interest in Buddhism. Others are true pilgrims invited by monks traveling abroad to come to a place they’d probably never heard of. Suddenly, spinning monsters Buddhism. It is a lot to take in.

Another perspective would see overcrowding of not always polite or informed foreign visitors, succeeding generations of monks variously knowledgeable and skilled in dance, and the exploitation of Cham festivals by the tourism industry with little in return. Tourism is here to stay; educating the steady flow of visitors with a tourism awareness campaign would in fact do more for Cham than video-recording it.

The monks don’t really tell much; a couple of monasteries have booklets, Hemis a good one, in three languages. Foreigners may not understand what they are seeing because the West has no comparable form of dance: a mystical, meditative, monstrous, communal danced gnosis, much less a word for it.

Reaching beyond the festival performance back to the dance training of the monks, to the older masters who have knowledge, and to the traditional manuscripts in each order that deal with Cham, a search and spotlight for basic principles of exterior movement and interior yogic techniques are possible. Bringing these to new attention, such as among the monks themselves, would be good for Cham.

The geographic range of Cham is vast, emanating from the Himalaya. What follows is a brief account of three monasteries in Ladakh-Zanskar: Sakti Gonpa, the only Nyingma lineage monastery in the region; Sani Gonpa, a Drukpa Kagyu monastery; and Korzok Gonpa, also Drukpa Kagyu, but with a different dance lineage. These three provide an example of the richness and complexity of Cham practice sustained there.

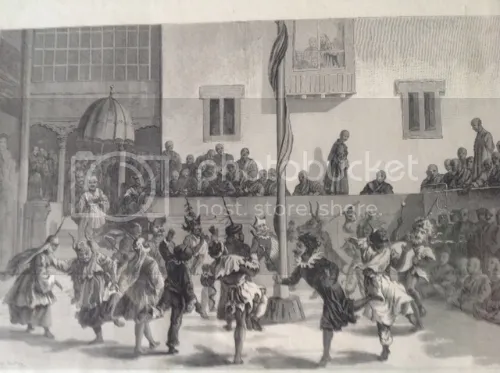

made on the British Mission to Yarkand. There are many historical inaccuracies

in the costumes and dance. Photo courtesy Hemis Monastery, gift of Core of

Culture, 2014. From Core of Culture

Within the Drukpa Kagyu today there is a dual lineage in leadership, each with a distinct dance tradition. The Northern Drukpa, led by the Gyalwang Drukpa, head of the famous and rich Hemis Monastery, have a well-known three-day Cham festival, more a masquerade than a ballet, a pageant in paces. The Southern Drukpa, however, still pledge allegiance to the order’s founder, Ngawang Namgyal, known in Bhutan as the Zhabdrung, who founded the country in 1616.

Do the Southern Drukpa in Zanskar perform the same complex and athletic dances as the Bhutanese Buddhists? I learned, yes, at least some (though I did not see every dance). They do not do the dances of the Hemis lineage of Cham. The deities, and their rituals and iconographic schematics, were different between the two Drukpa lines, and so too their Cham.

Sani Gonpa in Zanskar is home to perhaps the oldest Buddhist site in the entire region, dating to 127 CE. The Kushan king Kanishka the Great (r. c. 127–63) built a stupa here, and this ancient place is one of the eight great cremation grounds of tantric Buddhism. Here at Sani Gonpa, Drukpa Kagyu dances originating in Bhutan four hundred years ago are being maintained with integrity. This was a discovery. The Kingdom of Bhutan was in many ways a closed system, with no comparison possible until now.

Bhutan is mostly Alpine in appearance. Zanskar, by contrast, is the highest valley in the world, stony, rugged, and on a towering scale. Zanskar is more than twice the altitude of Bhutan. Vast, inhospitable distances are involved. The Zanskar dances were in high relief, more complex and energetic than much Cham choreography in the region. Perfectly transmitted, dance is a culture unto itself, one that delivers precise transmission in isolated places and is maintained centuries after being introduced.

Another remote example is seen at a festival far away from Zanskar, the Korzok Gustor. Held at Korzok Gonpa on Tsomoriri Lake, a Himalayan lake 17,000 feet high, it is possibly the highest dance festival in the world. This too is a Drukpa Kagyu monastery, but one connected to the Hemis Cham lineage, not Bhutan’s, so the dance was slower, more mummery than dance. It was also more of a family reunion as the community of Korzok is so small that when the monks came out in their normal robes to rehearse, the only thing heard was people from the community shouting at their brother or cousin, or at their son.

From Core of Culture

This festival was well danced and photographed—even monks and nuns love their devices. What was once a white plague is now a too-common thing, tripods placed anywhere, arm-reaching camera shots that can’t possibly be good. Filming festivals in Ladakh today is not an effective way to help the dances maintain excellence. Banning photography would be.

2014. From Core of Culture

The Nyingma are the oldest order of Vajrayana Buddhism, the most connected to sorcery, sacrifice, the Bon religion, psychic cultivation, and magic. It is also the most localized, with no ritual orthodoxy. Sakti, like Korzok, was a stop along caravan trade routes between Tibet, Yarkand, and Kashmir. Although remote, until the 1950s there was a regular flow of commerce and people. Opening these places to tourists renews a flow of visitors.

By means of this route, a particular Cham arrived at Sakti centuries ago. Otherwise, it exists in several variants only in Bhutan, although it is also performed in a number of Nyingma centers in the West. In this Cham, called The Eight Manifestations of Guru Rinpoche, each manifestation appears. Guru Rinpoche is the 8th century great adept from Swat near Afghanistan and the founder of Vajrayana Buddhism; a wizard and mystic, he is the inventor of Cham.

Guru Rinpoche has eight manifestations, ranging from Shakya Senge to Dorje Drolö, where he flies through the air on the back of his consort now transformed into a tigress. This impressive masquerade, a circular procession of each manifestation and its retinue, clearly shows that Cham is not synonymous with the word “dance.” This Cham is stately and patterned into types of pacings, staggered ways of walking, and mystical shape-shifting, until finally all the large-masked beings are revealed together. The eight manifestations, being seated, become family to everyone there. This Cham is a brilliant bringing together of the sublime and the mundane, a visionary dance that has traveled far.